He tasted her mouth.

After a while she undressed him.

His erection was like a post. When she touched it he felt a quick flash of guilt and remembered Irene. But that passed, and he slipped into a pool of sensation.

Afterward, she got two fresh bottles of Kirin. They sat up in bed, drinking. They touched one another, gently, tentatively, as if to reassure themselves that they had been together.

At some point in the night, after the Kirin was gone, when she was lying with her head upon his chest, he said, “I told you about my son.”

“Mike.”

“Yes. What I didn't tell you was that he thinks of me as a murderer.”

“Are you?”

“In a sense.”

“Who have you killed?”

“Agents. The other side.”

“How many?”

“Eleven.”

“They would have killed you?”

“Of course.”

“Then you're no murderer.”

“Tell him that.”

“The meek don't inherit the earth,” she said. “The meek are put in concentration camps. And graves.”

“I've tried to tell him that.”

“But he believes in pacifism and reason?”

“Something of the sort.”

“Wait until he finds most people won't listen to reason.”

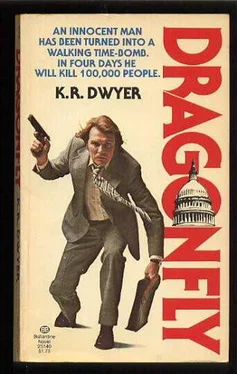

He cupped one of her breasts. “If I told him about Dragonfly, Mike would say the world has gone mad.”

“I think poor Bob McAlister feels that way. At least a little bit. Don't you think?”

“Yes. You're right.”

“And of course, it hasn't gone mad.”

“Because it's always been mad.”

She said, “You know why I wanted you?”

“Because I'm handsome and charming?”

“A thousand reasons. But, maybe most of all — because I sensed violence in you. Death. Not that you're fond of death and violence. But you accept it. And you can deal it.”

“That makes me exotic, exciting?”

“It makes you like me.”

He said, “You've never killed anyone.”

“No. But I could. I'd make a good assassin if I believed the man I was to kill had to die for the good of mankind. There are men who need to die, aren't there? Some men are animals.”

“My liberal friends would think I'm an animal if they heard me agree with you,” he said. “But then, so would some of my conservative friends.”

“And your son. Yet without you and a few others like you, they'd all have fallen prey to the real animals a long time ago. Most men who can kill without guilt are monsters, but we need a few decent men with that ability too.”

“Maybe.”

“Or maybe we're megalomaniacs.”

“I don't know about you,” he said. “But I don't always think I'm right. In fact, I usually think I'm wrong.”

“Scratch megalomania.”

“I think so.”

“I guess we're just realists in a world of dreamers. But even if that's what we are, even if we are right, that doesn't make us very nice people, does it?”

“There are no heroes. But, Miss Tanaka, you're plenty nice enough for me.”

“I want you again.”

“Likewise.”

They made love. As before, he found in her a knowledge and enthusiasm that he had never known in a woman, a fierce desire that was beyond any lust that Irene had ever shown. None of the very civilized, very gentle lovers he had had were like this. And he wondered, as he swelled and moved within her, if it was necessary to see and accept the animal in yourself before you could really enjoy life. Lee Ann rocked and bucked upon him, gibbered against his neck, clutched and clawed at him, and worked away the minutes toward a new day.

At twelve-thirty he put through a call to the desk and asked for a wake-up message at six the next morning. Then he set his travel clock for six-ten.

Lee Ann said, “I gather you don't trust Japanese hotel operators.”

“It's not that. I'm just compulsive about a lot of things. Didn't McAlister warn you?”

“No.”

“I have a well-known neatness fetish which drives some people crazy. I'm always picking up lint and straightening pictures on the walls…”

“I haven't noticed.”

Suddenly he saw the room-service cart, covered with haphazardly stacked, dirty dishes. “My God!”

“What's the matter?”

He pointed to the cart. “It's been there all night, and I haven't had the slightest urge to clean it up. I don't have the urge now, either.”

“Maybe I'm the medicine you need.”

That could be true, he thought. But he worried that if he lost his neuroses, he might also lose that orderliness of thought that had always put him one up on the other side. And tomorrow when they got into Peking, he would need to be sharper than he had ever been before.

HSIAN, CHINA: FRIDAY, MIDNIGHT

Steam blossomed around the wheels of the locomotive and flowered into the chilly night air. It smelled vaguely of sulphur.

Chai Po-han walked through the swirling steam and along the side of the train. The Hsian station, only dimly lighted at this hour, lay on his right; aureoles of wan light shimmered through a blanket of thin, phosphorescent fog. The first dozen cars of the train were full of cargo, but the thirteenth was a passenger cab.

“Boarding?” asked the conductor, who stood at the base of the collapsible metal steps that led up into the car. He was a round-faced, bald, and toothless man whose smile was quite warm but nonetheless unnerving.

“I'm transferring from the Chungking line,” Chai said. He showed the conductor his papers.

“All the way into Peking?”

“Yes.”

“And you've come from Chungking today?”

“Yes.”

“That's quite a trip without rest.”

“I'm very weary.”

“Come aboard, then. I'll find you a sleeping berth.”

The train was dark inside. The only light was the moonlike glow which came through the windows from the station's platform lamps. Chai could not really see where he was going, but the conductor moved down the aisle with the night sureness of a cat.

“You're going the right direction to get a sleeping berth,” the toothless man said. “These days the trains are full on their way out from the cities, on their way to the communes. Coming in, there are only vacationers and soldiers.”

In the sleeping cars, where there were no windows, the conductor switched on his flashlight. In the second car he located a cramped berth that was unoccupied. “This will be yours,” he said in a whisper.

All around them, three-deep on both sides, men and women snored and murmured and tossed in their sleep.

Chai threw his single sack of belongings onto the bunk and said, “When will we reach Peking?”

“Nine o'clock tomorrow evening,” the conductor said. “Sleep well, Comrade.”

Lying on his back in the berth, the bottom of the next-highest mattress only inches from his face, Chai thought of his home, thought of his family, and hoped that he would have good dreams. But his very last thought, just as he drifted off, was of Ssunan Commune, and instead of pleasant dreams, he endured the same nightmare that had plagued him since the end of winter: a white room, the gods in green, and the scalpel poised to dissect his soul…

WASHINGTON: FRIDAY, 3:00 P.M.

Andrew Rice ate a macaroon in one bite while he waited for McAlister's secretary to put the director on the line. He finished swallowing just as McAlister said hello. “Bob, I hope I'm not interrupting anything.”

“Not at all,” McAlister said guardedly.

“I called to apologize.”

“Oh?”

“I understand that you had to sweet-talk those federal marshals because I called them so late Wednesday evening.”

“It's nothing,” McAlister said. “I soothed everyone in a few minutes. It didn't even come close to a fist-fight.”

Читать дальше