The pale light of dawn made the tree trunks step forward out of the mist like dark silhouettes, a silently observing group of spectators with no knowledge of right or wrong, good or evil. Only the blind laws of nature and the circle of life and death, life and death. And the door between them.

I laid Robin down in the hollow I had dug next to a rock. I no longer knew whether the music I could hear existed only inside my head. Robin twitched and jerked, his fair skin in sharp contrast to the dark earth. His head moved from side to side and his eyes were wide open as he tried to scream through the duct tape.

“Hush,” I said. “Hush. ”

I ripped off the gag, and without paying attention to his pleading sobs I concentrated on the crowbar which I had driven into the ground on the other side of the rock. I calculated that it would take just one decent push forwards to make the rock tip over into the hollow. I rubbed my hands, which were covered in flakes of coagulated blood, and set to work.

As I grabbed hold of the crowbar I was aware of a movement out of the corner of my eye. Instinctively I looked over and saw a child. Its age was difficult to determine, because the face was so sunken that the cheekbones stood out. It was dressed in the remains of silky red pyjamas patterned with yellow teddy bears, and its chest was visible through the torn material. A number of ribs were crushed, and sharp fragments of bone had pierced the skin in several places.

The child raised its hands to its face. The nails were long and broken from scratching at rocks. And behind the fingers, the eyes. I looked into those eyes and they were not eyes at all, but black wells of hatred and pain.

Only then did I realise what I had done.

Before I had time to close my eyes or grab hold of the crowbar again, another small body hurled itself onto my back. I bent over and the child in pyjamas leapt up and seized me around the neck, burying its fingers just above my shoulder blades.

The body on my back ran its hands over my forehead, and then I felt jagged nails moving over my eyelids. I screamed as the sharp edges penetrated the skin on either side of the top of my nose, and blood ran down into my mouth. The child let out a single sharp hiss, then jerked its hands outwards.

Both my eyeballs were ripped out of my skull, and the last thing I heard before I lost consciousness was the viscous, moist sound of the optical nerves tearing, then a grunting, smacking noise as the children chewed on my eyes.

I don’t know how long I was out. When I came round I could no longer see any light, and I had no idea of the sun’s progress across the sky. There were empty holes in my head where my eyes had been, and my cheeks were sticky with the remains of my eyelids and optical nerves. The pain was like a series of nails being hammered into my face.

I pulled myself up onto my knees. Total darkness. And silence. The synthesiser’s batteries had given up. I fumbled around and found the crowbar, traced the surface of the rock until I reached the edge of the hollow, and was rewarded with the only sound that was of any importance now.

“Dad. Dad. ”

I crawled down to Robin. I bit through the tape around his wrists and ankles. I tore off my jacket and shirt and wrapped them around him. I wept without being able to shed any tears, and I fumbled in the darkness until he took my hand and led me back to the house.

Then he made a call. I couldn’t use the phone, and had forgotten every number. I was frightened when he spoke to someone whose voice I couldn’t hear. I groped my way to bed and sought refuge beneath the covers. That’s where they found me.

They say I’m on the road to recovery. I will never regain my sight, but my sanity has begun to return. They say I will be allowed out of here. That I will learn to adapt.

Robin comes to see me less and less often. He says he’s happy with his foster family. He says they’re nice. He says he doesn’t spend so much time playing games these days. He’s stopped talking about how things will be when I get out.

And I don’t think I will get out, because I don’t want to leave.

Food at fixed times and a bed that is made every day. I move blindly through the stations of each day. I have my routines, and the days pass. No, I shouldn’t be let out.

Because when I sit in the silence of my room or lie in my bed at night, I can hear the notes. My fingers extend in empty space, moving over an invisible keyboard, and I dream of playing.

Of replaying everything. Getting Annelie to visit me again and embracing her in the darkness, paying no heed to which doors are open or what might emerge through them.

There are no musical instruments in the unit.

Translated by Marlaine Delargy

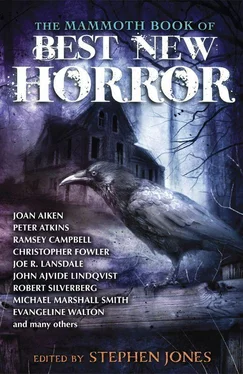

RAMSEY CAMPBELL

Passing Through Peacehaven

RAMSEY CAMPBELL’S MOST RECENT books from PS Publishing include the novels Ghosts Know and The Kind Folk , along with the definitive edition of the author’s early Arkham House collection, Inhabitant of the Lake , which includes all the first drafts of the stories, along with new illustrations by Randy Broecker.

Forthcoming from the same publisher is a new Lovecraftian novella, The Last Revelation of Glaaki .

Now well in to his fifth decade as one of the world’s most respected authors of horror fiction, Campbell has won multiple World Fantasy Awards, British Fantasy Awards and Bram Stoker Awards, and is a recipient of the World Horror Convention Grand Master Award, the Horror Writers Association Lifetime Achievement Award, the Howie Award of the H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival for Lifetime Achievement, and the International Horror Guild’s Living Legend Award.

He is also President of both the British Fantasy Society and the Society of Fantastic Films.

“Lord, it’s so long since I wrote ‘Passing Through Peacehaven’ — 2006 — that I don’t recall much about its genesis,” reveals Campbell about his second contribution to this volume.

“It was certainly suggested by overhearing announcements at a railway station, the kind of everyday occurrence that I may have taken for granted for most of my life until it suddenly turns around in my mind to display an unexpected side.

“Ideas are everywhere!”

**

“WAIT,” MARSDEN SHOUTED as he floundered off his seat. His vision was so overcast with sleep that it was little better than opaque, but so far as he could see through the carriages the entire train was deserted. “Terminate” was the only word he retained from the announcement that had wakened him. He blundered to the nearest door and leaned on the window to slide it further open while he groped beyond it for the handle. The door swung wide so readily that he almost sprawled on the platform. In staggering dangerously backwards to compensate he slammed the door, which seemed to be the driver’s cue. The train was heading into the night before Marsden realised he had never seen the station in his life.

“Wait,” he cried, but it was mostly a cough as the smell of some October fire caught in his throat. His eyes felt blackened by smoke and stung when he blinked, so that he could barely see where he was going as he lurched after the train. He succeeded in clearing his vision just in time to glimpse distance or a bend in the track extinguish the last light of the train like an ember. He panted coughing to a halt and stared red-eyed around him.

Two signs named the station Peacehaven. The grudging glow of half a dozen lamps that put him in mind of streetlights in an old photograph illuminated stretches of both platforms but seemed shy of the interior of the enclosed bridge that led across the pair of tracks. A brick wall twice his height extended into the dark beyond the ends of the platform he was on. The exit from the station was on the far side of the tracks, through a passage where he could just distinguish a pay phone in the gloom. Above the wall of that platform, and at some distance, towered an object that he wasted seconds in identifying as a factory chimney. He should be looking for the times of any trains to Manchester, but the timetable among the vintage posters alongside the platform was blackened by more than the dark. As he squinted at it, someone spoke behind him.

Читать дальше