Meanwhile, Witch House was published in 1945 as the initial title in the “Library of Arkham House Novels of Fantasy and Terror”, and her other novels include The Cross and the Sword and The Sword is Forged .

More recently, Centipede Press has published a new collection of the author’s work, Above Ker-Is and Other Stories , which includes four previously unpublished tales, and an expanded re-issue of her second novel, Witch House , which again contains bonus material.

During her lifetime, she was honoured with three Mythopoeic Fantasy Awards and two Locus Awards. She also received the World Fantasy Convention Award in 1985 and the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement in 1989.

At the time of her death, Walton left behind a number of unpublished novels, poems and a verse play. The author’s family has been working with Douglas A. Anderson in going through her papers, where they also discovered a handful of unpublished short stories. These include the tale that follows, which originally appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction .

Although the author had one story published in Weird Tales (“At the End of the Corridor” in the May 1950 issue), it appears from a letter to her agent, dated 8 May that same year, that “The Unique Magazine” rejected “They That Have Wings” for being “too gory”.

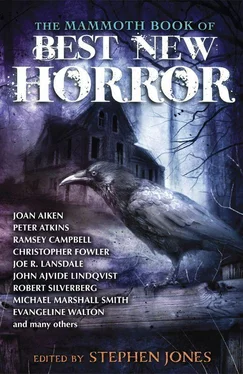

So, after more than six decades, it is my great pleasure to present this “lost” Weird Tales story of World War II by one of the genre’s most meticulous practitioners.

**

TWENTY-NINTH MAY: BERT Madden, Ronnie Lingard and I are in flight through the White Mountains. What will happen to us, God knows; we have become lost from the others, and there is no hope of succour. Nobody will come to look for us unless it is the Germans; nobody can come to look for us. We have known, ever since the at tempt to retake the Maleme airdrome failed, that Crete was lost.

We could go faster if it were not for Ronnie. He is British, a flier, who was left behind hospitalized when what remained of our wrecked air force (not over a dozen planes, I think) was or dered out of Crete. He is slight, fair-haired, a boy not yet out of his teens, I am sure, though he casually told us that he is twenty. To say that makes him feel more dignified; I know boys. He has a leg wound that causes him to limp, and Bert and I take turns supporting him. Bert tries to do more than his share; he is a huge man, tough and burly, a stockman from western Queensland. But al though I, John Ogilvy, was only a New Guinea schoolmaster before the war, scrawny and civilised and not used to using my muscles, I am as tough as he. As well able to help the lad.

If and while anybody can help him. There is still snow on the White Mountains. The winds cut like knives, and the barren rocks all about us rise to sharp points. Rocks that a man with two good legs can hardly climb. Not since yesterday have we seen any sign of human habitation, of other living beings. At first we did not mind; it was so good to get out of sight and sound of the Stukas, of the bombs and bullets that had been falling among us like a deadly, fiery hail. Little things that in a moment could change a man to a screaming, mutilated lump of flesh. Or leave no man at all; only a silent, bloody carcass.

But now we are beginning to be afraid. We must rest; we have stopped now; that is how, for the first time in days, I happen to be writing in this diary; it is easier to do that than to keep my hands still. But we cannot stay here; there is not an inch of dryness, of shelter, anywhere. Twice already Bert has helped Ronnie move. The boy does not want to; he wants nothing except to lie still. But if he does so for long at a time the warmth of his body (strange to think of warmth in our bodies!) melts the snow upon the rocks.

He is not strong, as Bert and I are. He will catch pneumonia if we stay here. And he must have food; none of us has eaten in more than forty-eight hours. Before too long we must all have food. A man can go only so long without—

A bird has just flown over us. Queer that the sight of a bird, the dark shadow of its wings upon the snow, should have the power to reduce three grown men to gibbering fear. But we all crouched and covered our faces, and Ronnie screamed; I dropped this book. Anything in the air above us still makes us think of a Stuka. And this was a very large, dark bird.

It has come back. It is circling low above us, as if curi ous. For a second, its dark, beady eyes met mine; more intelli gent, more sinister, than I ever thought a bird’s eyes could be. I cannot think what breed it is; I have never seen one like it, either in reality or in photographs. We cannot be frightened now; we know it is no plane; and yet something in the rustling of its wings, in that dark, moving shadow on the snow—

All of a sudden Bert turned over and fired at it, as it wheeled there in the air above us. I saw the revolver flash fire in his hand. The report, reverberating from rocky height to rocky height, was deafening. But the bird did not even seem frightened. It merely turned again, leisurely and lightly, in the air. Not hit; not disturbed.

Bert leaped to his feet, his face was convulsed with rage and fear. “Damn you!” he yelled. “We’ll get you! — not you us!” He emptied his revolver into it, it seemed — I have never known a better shot than Bert.

Yet still the bird wheeled on, calm, graceful there, low in the sky. Not a feather fell.

Ronnie laughed. “If there’s any eating done, it’s going to do it, old man. Not us.”

That is what we are afraid of, of course. Why our shot nerves did not quiet when we realised that there was no plane above us. The ancient danger, older than planes. The fate that, through the ages, has come upon unlucky travellers in deserts and upon men left dying upon battlefields. Rustling wings and tear ing beaks.

I laughed, but it was not a good laugh. I said, “Shut up, Ronnie. It’s not as bad as that, yet. Sit down, Bert.”

Bert sat down. His tanned, leathery face looked queerly pale; a kind of yellowish, mottled grey. He licked his lips.

“I can’t understand,” he said. “I ought to ’ve hit that thing. I ought to have hit it several times over.”

“It must be deaf,” I said, frowning. “I never heard of a bird so tame it wouldn’t run from gun-fire.”

We were all silent a moment, digesting that. The unnatural thing, the thing that has bothered me from the beginning. Then Bert cursed.

“That — thing ain’t no pet!” he said feelingly. “I’d hate to think who’d have it for a pet.”

And somehow, at those last words, we all shuddered; I do not know why.

“It seems to be watching us,” Ronnie said. “Look.”

And we did. We are. The bird is staying near us. For the last quarter of an hour it has been flying back and forth, back and forth, between the two great, snow-rimed cliffs that tower above us. Sometimes it flies lower, sometimes higher, yet always I have the feeling that it is edging a little nearer to us, a lit tle closer. I do not think it is healthy to watch it; its movements are like a queer kind of dance; they fascinate. And yet, somehow, I do not like to look away. To turn my back.

Soon the sun will be setting. We will not be able to see the creature so well then. To know exactly where it is.

There is already a rim of fire above the western cliffs. And as I noticed that, the bird’s small, beady eyes seemed to catch mine again; jewel-bright, night-black, like tiny corridors of pol ished jet leading down, down, into unfathomable darkness.

Perhaps Bert saw them too, for he caught my arm. “Give me your gun, Johnny! I ain’t got no more bullets. And the light’ll soon be gone!”

Читать дальше