“It sounds awesome.”

“Oh, it’s way beyond awesome. Go up there sometime when you’re older and see for yourself. Just be careful around the pole. The lightning has chipped up all kinds of loose scree, and if you started to slide, you might not be able to stop. And now, Jamie, I really do have to get rolling.”

“I wish you didn’t have to go.” I wanted to cry some more, but I wouldn’t let myself.

“I appreciate that, and I’m touched by it, but you know what they say—if wishes were horses, beggars would ride.” He opened his arms. “Now give me another hug.”

I hugged him hard, breathing deep, trying to store up the smells of his soap and his hair tonic—Vitalis, the kind my dad used. And now Andy, as well.

“You were my favorite,” he said into my ear. “That’s another secret you should probably keep.”

I just nodded. There was no need to tell him that Claire already knew.

“I left something for you in the parsonage basement,” he said. “If you want it. Key’s under the doormat.”

He set me on my feet, kissed me on the forehead, then opened the driver’s door. “This caa ain’t much, chummy,” he said, putting on a Yankee accent that made me smile in spite of how bad I felt. “Still, I reckon it’ll get me down the road apiece.”

“I love you,” I said.

“I love you, too,” he said. “But don’t you cry on me again, Jamie. My heart is already as broken as I can stand.”

I didn’t cry again until he was gone. I stood there and watched him back down the driveway. I watched him until he was out of sight. Then I walked home. We still had a hand pump in our backyard in those days, and I washed my face in that freezing-cold water before I went inside. I didn’t want my mother to see that I’d been crying, and ask me why.

• • •

It would be the jobof the Ladies Auxiliary to give the parsonage a good stem-to-stern cleaning, removing all traces of the ill-fated Jacobs family and making it ready for the new preacher, but there was no hurry, Dad said; the wheels of the New England Methodist Bishopric moved slowly, and we would be lucky to have a new minister assigned to us by the following summer.

“Let it sit awhile,” was Dad’s advice, and the Auxiliary was happy enough to take it. They didn’t get to work with their brooms and brushes and vacuums until after Christmas (Andy preached the lay sermon that year, and my parents almost burst with pride). Until then, the parsonage stood empty, and some of the kids at my school began to claim that it was haunted.

There was one visitor, though: me. I went on a Saturday afternoon, once more cutting through Dorrance Marstellar’s cornfield to evade the watchful eye of Me-Maw Harrington. I used the key under the doormat and let myself in. It was scary. I had scoffed at the idea that the place might be haunted, but once I was inside, it was all too easy to imagine turning around and seeing Patsy and Tag-Along-Morrie standing there, hand in hand, goggle-eyed and rotting.

Don’t be stupid , I told myself. They’ve either gone on to some other place or just into black nothing, like Reverend Jacobs said. So stop being scared. Stop being a stupid fraidy-cat .

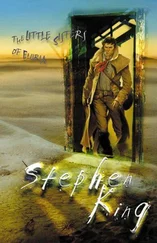

But I couldn’t stop being a stupid fraidy-cat any more than I could stop having a stomachache after eating too many hotdogs on Saturday night. I didn’t run away, though. I wanted to see what he had left me. I needed to see what he had left me. So I went to the door that still had a poster on it (Jesus holding hands with a couple of kids who looked like Dick and Jane in my old first-grade reader), and the sign that said LET THE LITTLE CHILDREN COME UNTO ME.

I turned on the light and went down the stairs and looked at the folding chairs stacked against the wall, and the piano with the cover down, and Toy Corner, where the little table was now bare of dominos and coloring books and Crayolas. But Peaceable Lake was still there, and so was the little wooden box with Electric Jesus inside. That was what he had left me, and I was horribly disappointed. Nonetheless, I opened the box and took Electric Jesus out. I set him at the edge of the lake, where I knew the track was, and started to reach up under his robe to turn him on. Then the greatest rage of my young life swept through me. It was as sudden as one of those lightning strikes Reverend Jacobs had talked about seeing up on Skytop. I swung my arm and knocked Electric Jesus all the way to the far wall.

“ You’re not real! ” I shouted. “ You’re not real! It’s all a bunch of tricks! Damn you, Jesus! Damn you, Jesus! Damn you, damn you, damn you, Jesus! ”

I ran up the stairs, crying so hard I could barely see.

• • •

We never did get another minister,as it turned out. Some of the local padres tried to take up the slack, but attendance dropped to almost nothing, and by my senior year of high school, our church was locked and shuttered. It didn’t matter to me. My belief had ended. I have no idea what happened to Peaceable Lake and Electric Jesus. The next time I went into the downstairs MYF room in the parsonage—this was a great many years later—it was completely empty. As empty as heaven.

Two Guitars. Chrome Roses. Skytop Lightning.

When we look back,we think our lives form patterns; every event starts to look logical, as if something—or Someone—has mapped out all our steps (and missteps). Take the foul-mouthed retiree who unknowingly ordained the job I worked at for twenty-five years. Do you call that fate or just happenstance? I don’t know. How can I? I wasn’t even there on the night when Hector the Barber went looking for his old Silvertone guitar. Once upon a time, I would have said we choose our paths at random: this happened, then that, hence the other. Now I know better.

There are forces.

• • •

In 1963, before the Beatlesburst on the scene, a brief but powerful infatuation with folk music gripped America. The TV show that came along at the right time to capitalize on the craze was Hootenanny , featuring such Caucasian interpreters of the black experience as the Chad Mitchell Trio and the New Christy Minstrels. (Perceived commie Caucasians like Pete Seeger and Joan Baez were not invited to perform.) My brother Conrad was best friends with Billy Paquette’s older brother, Ronnie, and they watched The Hoot , as they called it, every Saturday night at the Paquettes’ house.

At that time, Ronnie and Billy’s grandfather lived with the Paquettes. He was known as Hector the Barber because that had been his trade for almost fifty years, although it was hard to visualize him in the role; barbers, like bartenders, are supposed to be pleasantly chatty types, and Hector the Barber rarely said anything. He just sat in the living room, tipping capfuls of bourbon whiskey into his coffee and smoking Tiparillos. The smell of them permeated the whole house. When he did talk, his discourse was peppered with profanity.

He liked Hootenanny , though, and always watched it with Con and Ronnie. One night, after some white boy sang something about how his baby left him and he felt so sad, Hector the Barber snorted and said, “Shit, boys, that ain’t the blues.”

“What do you mean, Grampa?” Ronnie asked.

“Blues is mean music. That boy sounded like he just peed the bed and he’s afraid his mama might find out.”

The boys laughed at this, partly out of delight, partly in amazement that Hector was actually something of a music critic.

“You wait,” he said, and slowly mounted the stairs, yanking himself along by the banister with one gnarled hand. He was gone so long the boys had almost forgotten about him when Hector came back down carrying a beat-up Silvertone guitar by the neck. Its body was scuffed and held together with a hank of frayed hayrope. The tuning keys were crooked. He sat down with a grunt and a fart, and hauled the guitar onto his bony knees.

Читать дальше