Although,' Dante adds sheepishly, 'you might not think so.'

'On the contrary. It's a fine read. Although I haven't perused it for years. A little unsavoury in parts I fear, and there are far healthier ways to achieve enlightenment than experimenting with the black arts.'

'I see that as just a metaphor, for raising your consciousness. You know, like with poetry or meditation.'

The man nods, studying him for a time before speaking in the tone of a confidant. 'Well Dante, it may surprise you, but I have known Eliot for practically all of my adult life. We were at Oxford together.'

'I envy you that,' Dante says, out of his depth again.

'He has always been a good friend. But… and this might be hard for you to digest, particularly after coming so far, Eliot is not the man he was.'

Dante holds his breath.

'I can see confusion in you already, Dante, despite your admiration for him. But there have been hard times in his life and it is best that you are made aware of certain facts. It's only fair that I put you in the picture. He has problems. Serious problems. He is subject to embarrassing digressions and, well, some quite abnormal behaviour. You see, I doubt whether he's capable of writing the book.'

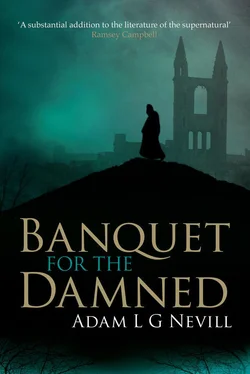

Arthur sighs. 'This is so hard. I find it so touching that his book has been such a positive influence on a young man, and on a musician too. But Eliot has been unwell recently. You could say he never really recovered from an unconventional youth. And to be absolutely honest, and you deserve nothing less, it was his travelling and certain episodes that Banquet was based upon that began his illness.' He emphasises the word 'illness', and raises his eyebrows as if to impart a further cryptic embellishment.

'But don't take this the wrong way, Dante. He was once a force to be reckoned with, and made an excellent contribution to his faculty.

But that was some time ago.' The man's voice softens. 'I tell you this in confidence. There are alcohol problems. And I'd hazard a guess that Eliot needs to attend to his personal problems now. Rather than launching into a new project. It's all quite serious, I'm afraid to say.'

'I don't believe this,' Dante mutters. 'It can't be right.'

'I know it must be difficult for you.'

'But the other day he was fine. I mean he was lucid and clever and —'

'There are rare moments of clarity, but on the whole, I am afraid…'

'What about his partner, Beth. Can't she help?'

Arthur closes his eyes for a second. 'Dante, perhaps we had better sit down.'

They sit on the other side of the hall, beside the refreshment tables. A short distance away from where they sit, Dante notices Tom. He holds a plate loaded with food and he speaks to a young blonde woman in a black dress. She stands close to him, smiling.

'Dante,' Arthur says, as soon as they are settled, 'Beth and Eliot have an unconventional arrangement. I am really not sure it is my place to divulge so much, but I think their days are numbered in this town. St Andrews is a quiet place. Young people come here to receive an excellent education, and there really is no room for the more unconventional aspects of academia. If you follow? A great risk was taken in inviting Eliot to lecture here. It was only his considerable knowledge of religion that encouraged the university to go out on a limb and invite a somewhat controversial figure here in the first place. Beth was a student of Eliot's, and their relationship did not befit his position. I am afraid he has let a great many people down. His students, his friends, and ultimately himself. I suppose I am trying to tell you that Eliot has been unethical. He lost his effectiveness a long time ago. Perhaps even in the fifties. Prison must have been hard for him.'

The words fall like axes. 'Prison?'

Arthur nods. 'Turkey. And Haiti.'

By looking at the floor, Dante attempts to conceal his shock.

'Over the last few years,' Arthur continues, 'Eliot began to drink again and suffer from certain lapses of memory. And, well, the rest has been a rather unfortunate mess. I am afraid he is incapable of taking lectures, and hasn't produced a credible paper in years. It is only through the generosity of another of our circle from Oxford, the Proctor, that he is still with us in a consultancy role.'

Dante sinks into his chair; the sounds of clinking glass and scraping cutlery amplify to a swirling clutter of noise in his ears, and his head feels unnaturally heavy. The voices in the hall are louder now, mocking, laughing at his impetuous journey and pitiful hopes of escape. If what this man says is true, he has driven four hundred miles to assist a man ridden with dementia. But what this Spencer says makes sense. It explains Janice's reaction when he first went to the school, as well as Eliot's cryptic dialogue, and the eyes of the staff tonight.

Arthur's voice seems to drift across to him from another dimension. 'So sorry, Dante. If there is anything we can do to help… Perhaps we can assist your interest in Eliot with our recollections. After all, we knew him in his prime. And what a prime. Captained his county, you know. One of the first to climb…' Arthur's voice trails off. His jowly face suddenly reddens.

'I believe I may command the best position to impart my résumé, Arthur.'

Dante sits stunned, bewildered by both Arthur's reaction and the unexpected sound of Eliot's voice. Arthur rises from out of his seat, wearing embarrassment on his face like clown paint. There is something else too, setting that grin fast and making his small eyes flick about. It appears as if he is frightened. Arthur Spencer looks down at Dante and mumbles something about a visit to his office on North Street.

'Sure,' Dante says.

'Bloody fool,' Eliot says, watching the Hebdomidar move away through the crowd on his journey back to Janice and the long-jawed man, who still watch with a keen interest. 'Over there, Dante, are three clever debunkers. You know what a debunker is? A person who lacks imagination, Dante. Who can only thrive in the material world. Their dull creed replaced spirituality with a new god of economics. But what has that achieved? People are dissatisfied, bored, unfulfilled. Those three can do nothing but mock the intuitive and the creative. Like us, Dante, who flee the everyday world and seek a meaning through our endeavours. We are the fortunate ones.' The words are bitter and come fast, Eliot's breath polluted by whisky, his eyes struggling to focus. But Dante finds the words exhilarating and far closer to what he loves about Banquet .

Eliot then slumps into the chair Arthur Spencer vacated. The speech appears to have exhausted him and, as he leans forward in his chair, he winces as if suffering from back pain. For a while he looks past Dante and glares at the trio across the hall, who finally turn their faces away. 'Forgive me, Dante.' His words are softer now. 'We were friends once. Good friends.'

Dante nods, inspired by Eliot's words and angry at himself for even daring to doubt the man. People like the Hebdomidar are clever orators, capable of playing with your emotions by feeding you lines. Every genius is despised in his own time, and he knows a thing or two about envy: the band scene at home is brutal. And, after all, what is a Hebdomidar? He has no idea, but the name conjures an association with administration. Maybe this Spencer is a money man. And Janice runs an office. How could they understand Eliot? 'I hear you,' Dante says.

'I know you would never doubt me, Dante. It is important that we trust each other. Am I right?'

'Absolutely.'

'Good. You would do well to steer clear of them. There is unfinished business and I do not want it interfering with our collaboration.'

'No. Not at all. I'm all yours, Eliot. You can trust me.'

'I know,' he replies, but looks away from Dante.

Читать дальше