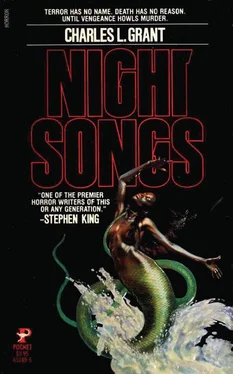

Charles Grant - Night Songs

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Charles Grant - Night Songs» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, на русском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Night Songs

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Night Songs: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Night Songs»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Colin Ross, twice thwarted in love, once abandoned, quit the mainland for Haven's End, a wounded soul on an idyllic island, seeking to heal his life.

But instead of peace, he is hurled into chaos. Some dark and ancient hatred, some evil force is unleashed, wreaking vengeance on the islanders, mangling the living and mutilating the dead.

And, as the piercing songs rise to meet the roaring wind, Colin Ross, against his will, is sucked into the raging storm.

Night Songs — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Night Songs», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She signed, her gaze shifted, and the ghost vanished.

To her left she could see the small fishing fleet moving ponderously homeward. Just over a half dozen boats, but they would work until November to drag the last of the harvest into their holds. Patiently. Confidently. Once each day drawing into a large circle for a laughing mealtime rendezvous if all was well, somberly trading well-worn and well-known gripes if their nets remained empty. Most had lived on the island since birth and could, if they'd a mind, trace their lineage back to the original inhabitants-brigands and smugglers and a few honest settlers, who lived on the island in an uneasy truce.

They fished, gossiped, and few ate what they carried back to Fox's Marina. Most of the catch was swiftly unloaded and packed into refrigerated crates, the crates labeled and thrown onto a truckbed for the mainland. What remained was sold to Naughton's Market or the Clipper Run. And if it were not worth the selling, it was thrown to the gulls.

The gulls that stalked them like winged hyenas.

Lilla watched them without a glimmer of caring, while the shadows of the trees behind the crumbling shack lanced toward the water, jabbed at the darkening sand. Shadows that would last until the night fog rolled it, riding low on the waves like a massive prowling beast, silently pacing the island in furtive spurts of roiling grey. It was treacherous even for the landed-blotting out the stars, defying the bright moon, sifting through the woodland to curl low in the streets, scrape noiselessly at chilled panes, fade the streetlamps one by one to slow sifting spots of diffused white haze.

Suddenly, there was a man walking along the beach. His topcoat was open, his hat back on his head, and his shoes were carried in one listless hand. He walked all the way to the first boulder without looking at the shack, turned and started back, to the snow fence that ran from the last jetty to the woods, the division between private and public bathing. He passed a hand wearily over his forehead, walking with a peculiar gait not caused by the sand-rigid, deliberate, difficult to watch without wanting to help him. He stopped and lifted his left foot, tried to slip on a shoe and fell on his rump. He shook his head and looked skyward, then looked at his shoes and tossed them away. Rising slowly with hands outstretched for balance, he dusted sand from his trousers and moved on, swaying slightly.

She watched him without blinking. Her arms were braced at her sides, her knees pressed against the unpainted wall beneath the canted window. Hearing the rising high tide without listening to it; listening instead to the calm rhythm of her heart. And when it was clear there was no panic to ruin what she'd done, she closed her eyes tightly and hugged herself snugly.

It would be so easy, she thought, to find Warren Harcourt and join him in his drinking. And it would be so temptingly easy to believe that belonging to the only black family on Haven's End had denied her grandfather all the care he'd needed. Too easy. Like running away with Harcourt. Like ignoring the fact that nothing could have saved Gran, nothing at all could have kept his lungs from stalling, his heart from failing. Ninety-seven years he had lived, and he had simply and finally worn himself out with his liquor and his smoking and his constant praying for that one little miracle that would bring him his fortune.

Dead now, when she needed him most.

Dead now, while men like Warren Harcourt stumbled on so damned worthless.

Dead. Gran had been her family, and he'd left her alone.

When she was sixteen, she had decided that either law or medicine would fill the rest of her life. No one in her family had ever been to college before, she would be the first, and she was going to do it right. Her parents applauded. Gran grumbled and told her he could teach her all she had to know, and she kissed his knotted brow, and whispered a laugh in his ear. Peg agreed to help wherever she could, and Little Matt promised to help her study very hard. And Colin her Knight (though he didn't know he had her armor) wrote to people he knew in hopes of snaring a scholarship or two.

When she was sixteen, the boys hung around her shyly, knowing her color and wanting her just the same. Instead of Peg, she asked Colin to help sort out her feelings, not because he was smarter but for the way he wouldn't look at her when he talked.

It was grand at sixteen, and with little ego involved she knew she was smart, she was pretty, she was ready for the world.

When she was sixteen, she and Gran had persuaded her parents to take a day off from running the Neptune Luncheonette. She assured them it would not fall apart or burn down or blow away while they were gone. When they hesitated, Gran scolded them lightly in Caribbean patois. They'd laughed and agreed, and rented a small boat from the marina to sail beyond the breakers.

In taking over the store, she had celebrated by treating every child to free ice cream sodas. And it was a celebration-the first full day the elder D'Grous had taken off since she could remember. Even during winter, when most shopowners fled for a three-month respite, they stayed. There was always work after the motels closed, and they felt more secure here, where there was no time for bigotry, or the mainland's tacit harassment.

By noon she was exhausted. A pleasant, high-flying weariness had her flirting, laughing, singing Caribbean songs old Gran had taught her when Mother wasn't around to disapprove of the choice.

She wore her grandfather out.

At five past two, Patrolman El Nichols walked in, and ten minutes later she was in the back room weeping in Gran's arms.

One of the fishermen had started back to the marina for repairs on his engine. On the way he found the sailboat, capsized after a noontime squall. There was no sign of the D'Grous.

When she was sixteen, Gran walked her to the house at the end of Atlantic Terrace where they drew the curtains, turned off the lights, refused to answer the telephone's pleading.

For weeks after the dying, the funeral without bodies, he had stayed, cleaning and cooking, promising all would be fine.

"You know, girl," he said one night at the table, "your old mother was the best woman I know, the best daughter there ever be. But she think I'm a little-" And he drew a circle around his temple and laughed quietly. "She don't remember the island, the other one. She was still very small, too small to walk, when…"

He stopped, and Lilla watched his eyes as they followed his mind away from Haven's End.

"Much sickness," he said softly. "I tell your Gram we have to leave, go to the Big Place and be rich. But she died, you see. Then I have… small trouble and come*too, with your mother."

"Gran, why didn't Momma want you to sing me the old songs?"

His look, then, was almost ferocious.

"Because," he said after too long a time, "she don't remember the true island and the things it can do. She likes it here and she wants you to grow up to be just like her."

"I want to, Gran."

"And I, girl. I promise your mother I give you this chance."

But he had promised her, too, her parents would come back, and they never did.

And he had promised he would guard her-and he'd died last week. The last of her family, when she needed him the most. When she needed him to tell her what to do with the store, her life, the lure of the mainland and all that lay beyond.

He had fallen ill just after Labor Day. He lay on the bed in the shack's back room and hadn't risen again. Instead, he spent long hours, the night hours, telling her of his boyhood on the Caicos Islands, north of Haiti. Very little made sense because he rambled on so much, whispered more often than not, broke into songs he demanded she learn. But his hoarse singing entranced her, until she sang with him, seeing him smile, nodding when she was able to complete a song on demand.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Night Songs»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Night Songs» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Night Songs» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.