In the woods beyond the plowed intersection, back toward what Bill would have called “the Bads,” a shivering adolescent boy wrapped in stinking, half-scraped hides watched the quartet standing in front of Dandelo’s hut. Die, he thought at them. Die, why don’t you all do me a favor and just die? But they didn’t die, and the cheerful sound of their laughter cut him like knives.

Later, after they had all piled into the cab of Bill’s plow and driven away, Mordred crept down to the hut. There he would stay for at least two days, eating his fill from the cans in Dandelo’s pantry — and eating something else as well, something he would live to regret. He spent those days regaining his strength, for the big storm had come close to killing him. He believed it was his hate that had kept him alive, that and no more.

Or perhaps it was the Tower.

For he felt it, too — that pulse, that singing. But what Roland and Susannah and Patrick heard in a major key, Mordred heard in a minor. And where they heard many voices, he heard only one. It was the voice of his Red Father, telling him to come. Telling him to kill the mute boy, and the blackbird bitch, and especially the gunslinger out of Gilead, the uncaring White Daddy who had left him behind. (Of course his Red Daddy had also left him behind, but this never crossed Mordred’s mind.)

And when the killing was done, the whispering voice promised, they would destroy the Dark Tower and rule todash together for eternity.

So Mordred ate, for Mordred was a-hungry. And Mordred slept, for Mordred was a-weary. And when Mordred dressed himself in Dandelo’s warm clothes and set out along the freshly plowed Tower Road, pulling a rich sack of gunna on a sled behind him — canned goods, mostly — he had become a young man who looked to be perhaps twenty years old, tall and straight and as fair as a summer sunrise, his human form marked only by the scar on his side where Susannah’s bullet had winged him, and the blood-mark on his heel. That heel, he had promised himself, would rest on Roland’s throat, and soon.

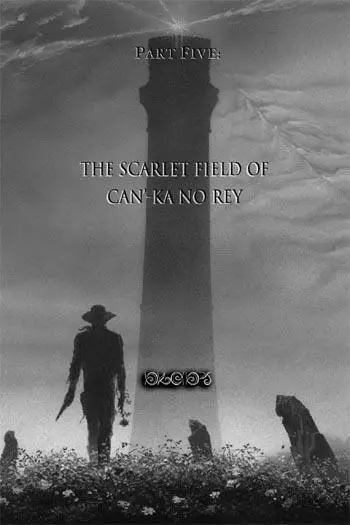

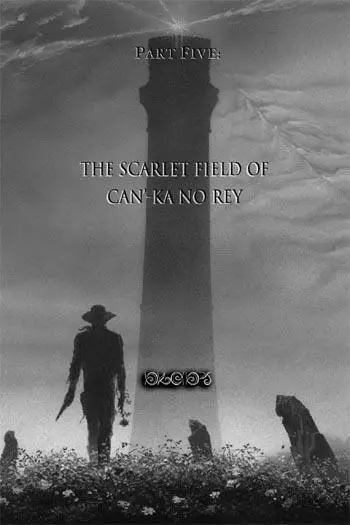

Part Five:

THE SCARLET FIELD OF CAN’-KA NO REY

Chapter I:

The Sore and the Door (Goodbye, My Dear)

In the final days of their long journey, after Bill — just Bill now, no longer Stuttering Bill — dropped them off at the Federal, on the edge of the White Lands, Susannah Dean began to suffer frequent bouts of weeping. She would feel these impending cloudbursts and would excuse herself from the others, saying she had to go into the bushes and do her necessary. And there she would sit on a fallen tree or perhaps just the cold ground, put her hands over her face, and let her tears flow. If Roland knew this was happening — and surely he must have noted her red eyes when she returned to the road — he made no comment. She supposed he knew what she did.

Her time in Mid-World — and End-World — was almost at an end.

Bill took them in his fine orange plow to a lonely Quonset hut with a faded sign out front reading

FEDERAL OUTPOST 19

TOWER WATCH

TRAVEL BEYOND THIS POINT IS FORBIDDEN!

She supposed Federal Outpost 19 was still technically in the White Lands of Empathica, but the air had warmed considerably as Tower Road descended, and the snow on the ground was little more than a scrim. Groves of trees dotted the ground ahead, but Susannah thought the land would soon be almost entirely open, like the prairies of the American Midwest. There were bushes that probably supported berries in warm weather — perhaps even pokeberries — but now they were bare and clattering in the nearly constant wind. Mostly what they saw on either side of Tower Road — which had once been paved but had now been reduced to little more than a pair of broken ruts — were tall grasses poking out of the thin snow-cover. They whispered in the wind and Susannah knew their song: Commala-come-come, journey’s almost done.

“I may go no further,” Bill said, shutting down the plow and cutting off Little Richard in mid-rave. “Tell ya sorry, as they say in the Arc o’ the Borderlands.”

Their trip had taken one full day and half of another, and during that time he had entertained them with a constant stream of what he called “golden oldies.” Some of these were not old at all to Susannah; songs like “Sugar Shack” and “Heat Wave” had been current hits on the radio when she’d returned from her little vacation in Mississippi. Others she had never heard at all. The music was stored not on records or tapes but on beautiful silver discs Bill called “ceedees.” He pushed them into a slot in the plow’s instrument-cluttered dashboard and the music played from at least eight different speakers. Any music would have sounded fine to her, she supposed, but she was especially taken by two songs she had never heard before. One was a deliriously happy little rocker called “She Loves You.” The other, sad and reflective, was called “Hey Jude.” Roland actually seemed to know the latter one; he sang along with it, although the words he knew were different from the ones coming out of the plow’s multiple speakers. When she asked, Bill told her the group was called The Beetles.

“Funny name for a rock-and-roll band,” Susannah said.

Patrick, sitting with Oy in the plow’s tiny rear seat, tapped her on the shoulder. She turned and he held up the pad through which he was currently working his way. Beneath a picture of Roland in profile, he had printed: BEATLES, not Beetles.

“It’s a funny name for a rock-and-roll band no matter which way you spell it,” Susannah said, and that gave her an idea. “Patrick, do you have the touch?” When he frowned and raised his hands— I don’t understand, the gesture said — she rephrased the question. “Can you read my mind?”

He shrugged and smiled. This gesture said I don’t know, but she thought Patrick did know. She thought he knew very well.

They reached “the Federal” near noon, and there Bill served them a fine meal. Patrick wolfed his and then sat off to one side with Oy curled at his feet, sketching the others as they sat around the table in what had once been the common room. The walls of this room were covered with TV screens — Susannah guessed there were three hundred or more. They must have been built to last, too, because some were still operating. A few showed the rolling hills surrounding the Quonset, but most broadcast only snow, and one showed a series of rolling lines that made her feel queasy in her stomach if she looked at it too long. The snow-screens, Bill said, had once shown pictures from satellites in orbit around the Earth, but the cameras in those had gone dead long ago. The one with the rolling lines was more interesting. Bill told them that, until only a few months ago, that one had shown the Dark Tower. Then, suddenly, the picture had dissolved into nothing but those lines.

“I don’t think the Red King liked being on television,” Bill told them. “Especially if he knew company might be coming. Won’t you have another sandwich? There are plenty, I assure you. No? Soup, then? What about you, Patrick? You’re too thin, you know — far, far too thin.”

Читать дальше