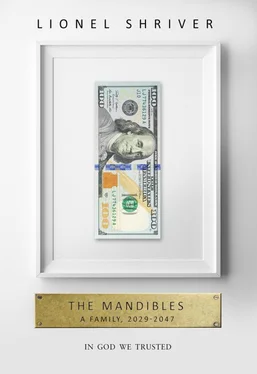

“I know this violates all your instincts. But the new reporting requirements on off-chip expenditures don’t come in until January. So before the public announcement about the bancor going cashless, which is going to flood the economy with bancors, and depress the exchange rate for cash transactions— you have to spend it .”

Nollie put the bowl down at last. “I’ve dodged them at every turn. Now I feel cornered. You’re not the only one who cherishes getting away with something.”

“Spend it on getting away with something, then.”

Nollie dried her hands on the dishtowel with an anxious twist. “Young people want money to buy things. Not only clothes and jewelry, but experience, thrills. Old people want money for one reason and one reason only: to feel safe.”

“You can never have enough money to be safe,” he said gently. “Money itself isn’t safe. We should know.”

“And how,” she seconded. “But then, life isn’t safe, at ninety years old.”

“Exactly,” he said. “The illusion of wealth is that it can buy what you want. Which it can, but only if you want, like, a pretty dress. You don’t want a dress. You want not to be old. We haven’t talked about it much, but don’t you wish one of those hothead boyfriends of yours had stuck around? Maybe you want to still be a famous writer, and you can’t buy that, either; there are no famous writers. Or you want to write with the same fire that lit you up when you started Better Late Than —the kind of fire that hardly anyone gets to keep. You want the thicker hair in your old snapshots. You pretend you don’t, but you want people to like you. You want not to get cancer. What threatens everything that’s important to you isn’t a cashless bancor, or currency depreciation, or debt renunciation, or economic collapse, but your own collapse. Other than being able to pick up, you know, a nice bottle of wine, or maybe a chicken, you can’t buy anything you want.”

“You kids think all we boomers have lived in a delusional bubble,” she returned. “Think it’s come as a shock I’ve got old? I’m not an idiot. I’ve been reading since I was your age about ‘elderly women’ raped and robbed in their homes, and in the back of my head I’ve heard a whisper: ‘Pretty soon, honey, that’s gonna be you.’ I’ve always anticipated becoming a target—defenseless, weak, and on my own. Maybe my parents had a premonition. Ever work it out? Enola is alone spelled backwards. So there was a discrete period in my forties when I had the opportunity to salt away some reserves, in preparation for a rainy day that might last decades—a monsoon—my own personal climate change. In my mind’s eye, I was stockpiling a veritably physical fortification. If I bricked the bills high enough, the barbarians couldn’t climb over. Less metaphorically? Maybe I could pay them to go away.”

“But that is delusional,” Willing said. “At your age, the main menace isn’t rapists and robbers, or waves of marauders in a second Dark Ages—or anything else from the outside. Every day, you face down the enemy within. So the one commodity that you bigging can’t buy, more than any other, is safety. Why doesn’t that release you? From trying to protect what you’re going to lose anyway? It should make you feel brave.”

“You’re one to talk about brave,” Nollie said bitterly, and her tonal turn injured him; he’d put a big effort into that soliloquy, which he thought had come out rather well. “Were you talking trash, for fun? Or have you seriously considered slumbering?”

“Yes,” he said. “I have.”

“So if I offered to spend the bancors on putting you into a self-induced coma for five years, you’d take me up on it.”

In truth, the proposal was immediately tempting. “You say that with disgust. But would five more years of ass-wiping at Elysian Fields improve on sleep? I love to sleep.”

“Willing.” Arms folded, she confronted him square on, her back to the counter, trapping him against the stove with that look. She was so much shorter than he was; he was damned how she managed to seem daunting. “I don’t often play the elder, and deliver judgment from on high. So hear me out this once. All through the early thirties, you were sly. Resourceful. Inventive. Disobedient. Impossible to intimidate. I used to love watching you stand your ground with that cretin Lowell Stackhouse, though he was three times your age. There was a somethingness about you. Sorry. I’m not as articulate as I used to be. Too many brain cells down. Too much homemade hooch. But the somethingness, it’s what fiction writers like me—former fiction writers like me—it’s what we always try to pin to the page. We always fail. That doesn’t mean it isn’t out there, only that it’s impossible to capture, like those tiny, nefariously evasive moths you can’t grab from the air. Even at Citadel. You worked so hard. You savored the effort. You were tilling fields like an ox, and the somethingness only thrived. But ever since the chipping, you’ve gone gray. You seem like other people. The boy I knew in 2030 would never have squandered his great-aunt’s resources on sleep .”

“The chip,” he said. “I doubt it’s messed with my mind in the way you’re implying. They’re not that clever. It probably is merely a means of accounting. Though a means of accounting that won’t let me cross the street against the light.”

“Cheating,” Nollie agreed, “is restorative. It maintains your dignity. Breaking a rule a day keeps the doctor away far better than a fucking apple.”

“In the fields at Citadel,” he went on, “we had plenty of time to talk. Avery told me about how hard it was for cancer patients when they got better. She said that when you’re bigging sick, making it to the next day is a victory. When you’re well again, being alive isn’t a triumph anymore. She said patients often got depressed not during chemo, but after it had worked. For me, the thirties. They were exciting. Our whole family—over and over, we almost died. When the fleX service went down on the trek to Gloversville, and we had to rely on Esteban, and on the paper map I stole from a recharging station—there was no guarantee we were going to make it. It was a miracle the recharging station even carried a paper map to steal. Carter could barely walk, because of his knees. Bing had something like trench foot, from his shot-out shoe and wet socks. And then we got to that narrow, unpaved drive and found the tiny label on the mailbox, CITADEL? We cried . But now. It’s this grinding in place. No horizon, no direction, and no threat. We may not keep much of my salary, but we’ll probably be all right, even without your bancors. That’s part of the problem. The okayness. The nothing but okayness. So chip or no chip. It’s not exciting.”

“Well, then,” Nollie announced decisively. “We won’t buy safety. We’ll buy excitement.”

Willing discovered the very next afternoon, as he had as a boy, that the most exciting excitement is free.

Nollie frowned. “You’re back early. Were you fired?”

“I fired,” he said, his breath quick. “It’s not a passive construction.”

“What?”

“I never really expected it at Elysian,” he said, pacing. He was probably disheveled. The way you look after you’ve squeezed into a linen cupboard. “Nothing happens there. Even when people die, it’s more nothing-happening. It’s expected. Or not-dying. That’s expected, too. I carry because I always have, since I was sixteen. Call it a fetish. A dependency. And I’m not the only one. You need money to feel safe, but I don’t trust money. After our whole family was forced from this house at midnight in the rain, I need a gun. I like the fact that, like you said, it’s against the rules. For most people, packing is a bigging bad idea. The Supreme Court was right. But it’s not a bad idea for me.”

Читать дальше