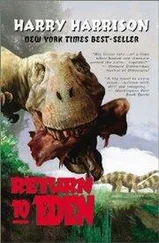

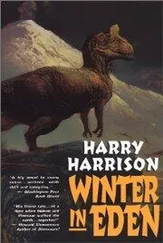

West of Eden

by Harry Harrison

8:And the LORD God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.

16:And Cain went out from the presence of the LORD, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden.

GENESIS

The great reptiles were the most successful life forms ever to populate this world. For 140 million years they ruled the Earth, filled the sky, swarmed in the seas. At this time the mammals, the ancestors of mankind, were only tiny, shrew-like animals that were preyed upon by the larger, faster, more intelligent saurians.

Then, 65 million years ago, this all changed. A meteor six miles in diameter struck the Earth and caused disastrous atmospheric upheavals. Within a brief span of time over seventy-five percent of all the species then existent were wiped out. The age of the dinosaurs was over; the evolution of the mammals that they had suppressed for 100 million years began.

But what if that meteor had not fallen?

What would our world be like today?

I have read the pages that follow here and I honestly believe them to be a true history of our world.

Not that belief was easy to come by. It might be said that my view of the world was a very restricted one. I was born in a small encampment made up of three families. During the warm seasons we stayed on the shore of a great lake rich with fish. My first memories are of that lake, looking across its still water at the high mountains beyond, seeing their peaks grow white with the first snows of winter. When the snow whitened our tents, and the grass around as well, that would be the time when the hunters went to the mountains. I was in a hurry to grow up, eager to hunt the deer, and the greatdeer, at their side.

That simple world of simple pleasures is gone forever. Everything has changed — and not for the better. At times I wake at night and wish that what happened had never happened. But these are foolish thoughts and the world is as it is, changed now in every way. What I thought was the entirety of existence has proved only to be a tiny corner of reality. My lake and my mountains are only the smallest part of a great continent that stretches between two immense oceans. I knew of the western ocean because our hunters had fished there.

I also knew about the others and learned to hate them long before I ever saw them. As our flesh is warm, so is theirs cold. We have hair upon our heads and a hunter will grow a proud beard, while the animals that we hunt have warm flesh and fur or hair, but this is not true of Yilanè. They are cold and smooth and scaled, have claws and teeth to rend and tear, are large and terrible, to be feared. And hated. I knew that they lived in the warm waters of the ocean to the south and on the warm lands to the south. They could not abide the cold so did not trouble us.

All that has changed and changed so terribly that nothing will ever be the same again. It is my unhappy knowledge that our world is only a tiny part of the Yilanè world. We live in the north of a great continent that is joined to a great southern continent. And on all of this land, from ocean to ocean, there swarm only Yilanè.

And there is even worse. Across the western ocean there are even larger continents — and there there are no hunters at all. None. But Yilanè, only Yilanè. The entire world is theirs except for our small part.

Now I will tell you the worst thing about the Yilanè. They hate us just as we hate them. This would not matter if they were only great, insensate beasts. We would stay in the cold north and avoid them in this manner.

But there are those who may be as intelligent as hunters, as fierce as hunters. And their number cannot be counted but it is enough to say that they fill all of the lands of this great globe.

What follows here is not a nice thing to tell, but it happened and it must be told.

This is the story of our world and of all of the creatures that live in it and what happened when a band of hunters ventured south along the coast and what they found there. And what happened when the Yilanè discovered that the world was not theirs alone, as they had always believed.

Isizzo fa klabra massik, den sa rinyur meth alpi.

Spit in the teeth of winter, for he always dies in the spring.

Amahast was already awake when the first light of approaching dawn began to spread across the ocean. Above him only the brightest stars were still visible. He knew them for what they were; the tharms of the dead hunters who climbed into the sky each night. But now even these last ones, the best trackers, the finest hunters, even they were fleeing before the rising sun. It was a fierce sun here this far south, burningly different from the northern sun that they were used to, the one that rose weakly into a pale sky above the snow-filled forests and the mountains. This could have been another sun altogether. Yet now, just before sunrise, it was almost cool here close to the water, comfortable. It would not last. With daylight the heat would come again. Amahast scratched at the insect bites on his arm and waited for dawn.

The outline of their wooden boat emerged slowly from the darkness. It had been pulled up onto the sand, well beyond the dried weed and shells that marked the reach of the highest tide. Close by it he could just make out the dark forms of the sleeping members of his sammad, the four who had come with him on this voyage. Unasked, the bitter memory returned that one of them, Diken, was dying; soon they would be only three.

One of the men was climbing to his feet, slowly and painfully, leaning heavily on his spear. That would be old Ogatyr; he had the stiffness and ache in his arms and legs that comes with age, from the dampness of the ground and the cold grip of winter. Amahast rose as well, his spear also in his hand. The two men came together as they walked towards the water holes.

“The day will be hot, kurro,” Ogatyr said.

“All of the days here are hot, old one. A child could read that fortune. The sun will cook the pain from your bones.”

They walked slowly and warily towards the black wall of the forest. The tall grass rustled in the dawn breeze; the first waking birds called in the trees above. Some forest animal had eaten the heads off the low palm trees here, then dug beside them in the soft ground to find water. The hunters had deepened the holes the evening before and now they were brimming with clear water.

“Drink your fill,” Amahast ordered, turning to face the forest. Behind him Ogatyr wheezed as he dropped to the ground, then slurped greedily.

It was possible that some of the creatures of the night might still emerge from the darkness of the trees so Amahast stood on guard, spear pointed and ready, sniffing the moist air rich with the odor of decaying vegetation, yet sweetened by the faint perfume of night-blooming flowers. When the older man had finished he stood watch while Amahast drank. Burying his face deep in the cool water, rising up gasping to splash handfuls over his bare body, washing away some of the grime and sweat of the previous day.

“Where we stop tonight, that will be our last camp. The morning after we must turn back, retrace our course,” Ogatyr said, calling over his shoulder while his eyes remained fixed on the bushes and trees before him.

“So you have told me. But I do not believe that a few days more will make any difference.”

“It is time to return. I have knotted each sunset onto my cord. The days are shorter, I have ways of knowing that. Each sunset comes more quickly, each day the sun weakens and cannot climb as high into the sky. And the wind is beginning to change, even you must have noticed that. All summer it has blown from the southeast. No longer. Do you remember last year, the storm that almost sank the boat and blew down a forest of trees? The storm came at this time. We must return. I can remember these things, knot them in my cord.”

Читать дальше