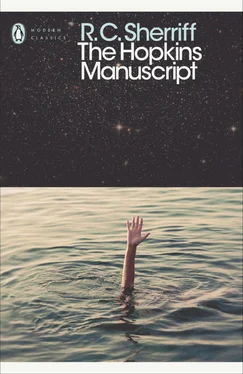

Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, humor_satire, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopkins Manuscript

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:978-0-241-34908-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopkins Manuscript: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopkins Manuscript»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopkins Manuscript — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopkins Manuscript», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was the custom of the people in my neighbourhood to meet, towards sunset, in Kensington Gardens, where we went to draw our daily bucket of water from the Round Pond. On fine evenings we would set our buckets down, stroll amongst the trees and pass the time of day.

We were a strangely assorted little community of about fifty people, varying in appearance and condition according to our temperaments, ability to hunt well, and our will to live. One old gentleman, with snow-white hair, invariably wore a buttonhole and always appeared, by some miracle of resourcefulness, sprucely dressed and immaculately clean. He had been a stockbroker in a very big way, I was told, and still lived amongst the ruins of his Park Lane mansion. In contrast came an old woman in whose hunting area must have lain a well-stocked wine store. She appeared every evening at the Pond, bleary-eyed and garrulous, her voice too blurred and thick to understand. But for the most part they were quiet, wistful people who talked and moved as if they were taking part in some ghostly charade. All of us were in middle age, for the ‘recruiting lorries’ had long since carried away the few young people that remained.

It was by the Round Pond that I met Professor Bransbury, and from him that I learnt all about the man who called himself ‘Selim the Liberator’.

Bransbury had been at Cambridge a few years before me, but we found much in common and several mutual acquaintances of our far-off student days. It became our custom to wander off together, to find a seat amongst the wild, unkempt shrubberies and to talk till twilight came.

He had been a Professor of Economics at London University – a man of wide reading and deep culture – Robinson Crusoe-like with his long-matted beard and straying locks of iron-grey hair. He wore a tattered morning coat with an open-necked cricket shirt and carried an old fur-lined motor rug that he had made into a kind of cloak. He told me the scraps of news that drifted into the ruined city, and one evening he casually remarked: ‘I hear that Selim is in Berlin.’

‘Selim?’ I enquired. ‘Who is Selim?’

Bransbury stared at me with wide, incredulous eyes. ‘My dear fellow,’ he began. ‘Selim! – surely you know!’

‘I know nothing,’ I replied, ‘for the past two years I have been buried in the country – completely isolated – without a word of news.’

‘You’ve never heard of Selim! – good heavens, man…’

‘Tell me who he is,’ I said.

My request for information pleased the old Professor. His instinct for teaching was awakened – he leaned back in the rotting Park seat and began in a dreamy voice – with faraway eyes.

‘You amaze me. I thought the whole world knew of Selim by this time. Selim, as far as I know, is a Persian, the son of a small local official who lived in Teheran. Apparently he was known in a small way for some years before the cataclysm. He was a revolutionary – possibly an anarchist. He preached against the exploitation and oppression of the Eastern peoples by the white nations of the West.

‘But it was the moon that made him. Whether he is a divine leader or a rank charlatan we shall never know. The fact remains that his magnetic power amounts to genius. By some means he discovered the secret of the moon’s approach before it was evident to the naked eye. He declared to his followers that the moon was the God of Oppressed Peoples: that very soon the Moon God would descend upon the earth to destroy their hated white oppressors.

‘I imagine his followers took it with a pinch of salt at first, but when it became evident that the moon was actually growing bigger and brighter every night, Selim’s name was made. His fame spread like a forest fire to every corner of the Eastern world, and he lost no time in cashing-in upon the superstition of those ignorant millions. He trained the best of his followers and sent a hundred young disciples to spread the word. To millions Selim became a god himself: a divine messenger from the silver god that was rushing to their aid from the skies above.

‘He had a big stroke of luck when the moon landed in the Atlantic. It would have been a different matter if it had landed on Selim himself, but he was able to announce that the Moon God had arrived: that it had crushed the white tyrants of Europe, leaving a miserable remnant for the oppressed peoples themselves to destroy as a sacrifice in honour of their deliverance. He called upon his followers to prepare for the Great Pilgrimage.

‘But Selim has a level head. He knew that Europe was by no means destroyed as completely as he had announced to his followers. All through those two years when Europe was re-gathering its strength and struggling back to life, Selim was collecting his hordes upon the plains of Turkestan. They came in their thousands to his camp – from the mountains of Afghanistan and the jungles of Africa – from China and Abyssinia – from India and the deserts of Arabia.

‘He trained them in discipline and in the use of arms, but he need not have gone to so much trouble. By the time his Holy Pilgrimage was ready to start our silly little leaders in Europe were busily at work destroying one another.

‘The Selimites swept in seething hordes across the Steppes of Russia and the eastern hills of Turkey: they were across the Volga – into Poland and the Balkans before our European leaders came to their senses.

‘A Congress of startled little Deputies met at The Hague about a year ago and patched up a hasty alliance against what they called “The Eastern Menace”. Even then they squabbled for months as to who should be “Leader-in-Chief”. In the end a Dutchman named van Hoyden took command…’

Dusk was coming. It was almost dark beneath the trees of the Park, and we were quite alone.

As Bransbury had been talking I had watched our small community file through the Park gates with their pails of water… dejected little animals, they seemed, in tattered clothes and grotesque, shapeless hats, creeping back to their ruined homes for another lonely night. The Professor’s story, strange though it was, had not surprised me. For a long time I had known instinctively that some deeper menace must have arisen to account for the hopeless collapse of our organised life. It explained two other things to me: Pat’s reference in her letter to our soldiers moving eastwards – Robin’s mystifying account of a fight with ‘black men’ in the forests of Bohemia…

‘What happened then?’ I asked.

‘Who knows?’ replied the old man. ‘There is no news – no touch with our men in Europe: only vague, scattered rumours come to us here. Van Hoyden, by all accounts, is a brave leader, and he has brave men to follow him. But what can a few thousands do against these seething millions? – a few thousand starving, bewildered, worn-out men who have fought each other and worn their guns out upon each other for three desperate years?

‘Last week I heard that the Selimites were in Vienna and Berlin – that they had sacked Venice and Milan. There was talk of van Hoyden making a stand upon the Rhine, but I heard the guns quite clearly last night… much nearer than the Rhine…’

‘It need not have happened,’ I whispered. ‘If Europe had remained united we could have scattered them to the winds…’ I was past all anger now. I had listened to Bransbury as if he were relating some legend of the Ancient World. I was living as those around me were living: in a fantasy of dreams that had no further kinship with this earthly world. ‘It need never have happened.’

‘Many things need never have happened,’ returned the old man in a low, patient voice. ‘It’s nearly dark. I think we ought to go.’

A young family of rabbits scuttled through the wild undergrowth as we walked in silence to the gates of the Park. I bade ‘goodnight’ to the Professor and hurried as fast as possible up the steep lane to the shelter of my home, for the baying of the starving dogs came ominously through the gathering darkness.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopkins Manuscript» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.