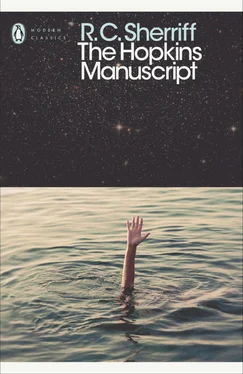

Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, humor_satire, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopkins Manuscript

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:978-0-241-34908-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopkins Manuscript: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopkins Manuscript»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopkins Manuscript — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopkins Manuscript», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It ain’t too late to put another acre under turnips,’ said old Humphrey.

I was surprised that the old man understood. ‘Splendid!’ I exclaimed. ‘For my own part I’ll put in another ten rows of late potatoes. I’ll keep those new pullets out of the market to increase our winter egg supplies.’

I glanced towards Robin, hoping for a response, but the boy was impatiently looking at his watch.

‘It’s nearly ten,’ he said. ‘We’d better load the car.’

When we arrived at Mulcaster Market we found the town bewildered and dismayed. I had hoped that a short respite at least would lie between Jagger’s speech and the day when Jagger began his ‘drive’ – but I was quickly disillusioned.

On the previous night, the town had been jubilant at the long awaited arrival of a trainload of steel girders for the new Town Hall. At dawn next morning, when a gang of workmen had gone to unload, they discovered to their astonishment that the train had disappeared. Under cover of darkness, in accordance with urgent orders from the Government, the train had been shunted out and its load of steel girders taken away to an ‘unknown destination for special military use’.

It was a crushing blow to Mulcaster. They had waited weeks to get those girders and the whole progress of their ‘Ten-Year Reconstruction Plan’ depended on them. To me it was damning proof of Jagger’s headlong stupidity. However much he needed the girders for tanks or guns he should never have called them back when once the people of Mulcaster had set eyes upon them. It was pitiful to see that brave little town, by one stupid Government order, cast from the heights of optimism to the depths of disappointment and despair. I left the town as early as possible that day. I could not bear to see those loitering, aimless people whose employment had gone with such tragic, unexpected swiftness.

We got home early enough to hear the evening radio news: to hear that Jagger had that day despatched an army of 10,000 men to garrison the British corridor across the moon to ‘protect our vital interests’. We also heard an impassioned speech by a man I had never heard of: a Mr Justin Wheelwright, new Minister of War. He appealed for 200,000 men to volunteer at once. They were to proceed to the Military Training Centre at Aldershot.

Two days later we heard that fighting had broken out in Normandy, upon the north-eastern fringes of the moon. The war was on.

Military historians, in days to come, may take the task in hand, but it will need men of superhuman genius to give sense and logic to that tangled, fruitless war.

The news we received was heavily censored. We were told of ‘magnificent victories’ and ‘astonishing progress’. One evening, with a blast of official jubilation, came the news that our Army of the Corridor had reached the Mediterranean and established touch with the survivors of the Gibraltar garrison. ‘Britain reaches the sea!’ – ‘The British Empire saved!’ – ‘A glorious peace in sight!’ cried the radio. ‘Our mighty purpose is all but achieved!’ boomed Jagger. ‘The corridor is ours! We shall build a bulwark of Blood and Iron: a mighty bulwark of British courage will starve greed and suspicion into surrender! As guardians and trustees of the moon’s great wealth we shall dispense fair play and give equal shares to every nation in the world!’

I must admit that even I was thrilled by the news and stuck out my chest. I was proud to belong to a great people whose crusade for peace and justice was carrying all before it. For a space dejection lifted from the town of Mulcaster: they hung an old Union Jack from the unfinished skeleton of the new Town Hall.

But that was in the summer time. Autumn came and winter loomed through a haze of menace and gathering suspense.

It was clear that Jagger had taken Europe by surprise and carried all before him in the opening campaign, but news crept through by way of foreign radio, and we learnt of the ‘Confederated Army of Europe’.

It seems that Jagger’s dramatic rise to power had impressed the Leaders of Europe so deeply that they made friends with one another. They came to the unanimous conclusion that the destruction of Jagger was essential before they could proceed with their long-looked-forward-to destruction of each other.

One morning an aeroplane scattered pamphlets over Britain, and a copy came down in the garden of Mr Wilkins’ house in Mulcaster. It was addressed to ‘The People of Britain’ by ‘The Confederated States of Europe’. It told us not to lose hope, because the Confederated States had solemnly agreed to destroy Jagger and release the British people from the toils of a mad usurper who was leading us to destruction. The people of Mulcaster did not consider this quite fair upon Jagger, but it certainly made them think.

A few weeks later a broadcast in English was given from Amsterdam. It announced that the Confederated Army had forced its way across the British corridor and cut our forces into two. ‘The Southern Army is isolated and starving into surrender. The Northern Army is in retreat to Britain’.

The news stunned us. It was vigorously denied by Jagger, but the denial lacked conviction. With the news came winter and the grinning spectre of famine.

Desperately I sought to drown my misery in work upon my farm, and those who toiled beside me were staunch and loyal. The Poultry Show that I had striven so hard to organise, was cancelled. The heart and soul had gone from Mulcaster. For a while they had hoped for victory and peace by autumn: they had desperately hoped to start once more upon the reconstruction of their town. But now their fine roads, begun with such brave endeavour, lay derelict and weed-grown – the wind sighed through the rusting framework of the new Town Hall and men walked the streets with bowed heads and hollow eyes.

Voluntarily I gave one half of all our produce to ‘The National Pool’. Once a week we drove to Mulcaster with all that we could spare, and the pale, dejected people watched our fine brown eggs and succulent vegetables loaded by soldiers upon Army lorries and driven off to the training camp at Aldershot.

Throughout that winter our fragile civilisation clung together by a miracle. There was hunger and misery: insistent calls for men: urgent and still more urgent calls for courage and renewed resolve.

‘The Confederated States’ swept our army from the corridor, and sometimes, in the long, dark evenings, creeping up that silent valley, came the sound of guns.

By Christmas we learnt that the Confederation had collapsed. The leaders of it had come at last within grasping distance of the wealth upon the moon, but as they stretched forth to clasp it, they began to knock each other’s hands away; they began to argue about their rights once more: they began to fight. By June the fighting had spread through the limbs of Europe like disease through a weak, resistless body.

Autumn came once more, and with it the day I dreaded: the day that I had known for a long time must come.

It was in the twilight of an October evening when Robin came to me. I was closing the hatches of my chicken houses as he came up the slope of the downs. He stood there for a little while, talking of casual things: of the way the seedling trees had grown that summer – of how the sunset caught the windows of our house and made it seem as if every light were on within it. And then he turned his head away, brushed his hair back from his forehead with a characteristic little movement that always betrayed him in embarrassment.

‘I don’t know what you’ll think, Uncle – but I’ve got to go.’

‘Go?’ I echoed. My heart fell with the weight of lead. For many months I had known that this must happen; yet now that it had come it seemed unreal and dreamlike… ‘Go where?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopkins Manuscript» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.