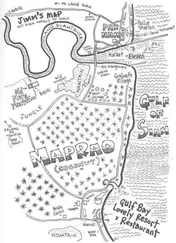

The liaison officer studied the chart of the Pacific. He laid his finger on the mass of reefs and island groups south of Hawaii. "There’s not going to be much relaxing when we come to navigate through all this stuff, submerged. And that comes at the end of the trip."

"I know it." He stared at the chart. "Maybe we’ll move away towards the west a trifle, and come down on Fiji from the north." He paused. "I’m more concerned about Dutch Harbor than I am of the run home," he said.

They stood studying the charts with the operation order for hail an hour. Finally the Australian said, "Well, it’s going to be quite a cruise." He grinned. "Something to tell our grandchildren about."

The captain glanced at him quickly, and then broke into a smile. "You’re very right."

The liaison officer waited in the cabin while the captain rang the admiral’s secretary in the Navy Department. An appointment was made for ten o’clock the following morning. There was nothing then for Peter Holmes to stay for; he arranged to meet his captain next morning in the secretary’s office before the appointment, and he took the next train back to his home at Falmouth.

He got there before lunch and rode his bicycle up from the station. He was hot when he got home, and glad to get out of uniform and take a shower before the cold meal. He found Mary to be very much concerned about the baby’s prowess in crawling. "I left her in the lounge," she told him, "on the hearthrug, and I went into the kitchen to peel the potatoes. The next thing I knew, she was in the passage, just outside the kitchen door. She’s a little devil. She can get about now at a tremendous pace."

They sat down to their lunch. "We’ll have to get some kind of a playpen," he said. "One of those wooden things, that fold up."

She nodded. "I was thinking about that. One with a few rows of beads on part of it, like an abacus."

"I suppose you can get playpens still," he said. "Do we know anyone who’s stopped having babies—might have one they didn’t want?"

She shook her head. "I don’t. All our friends seem to be having baby after baby."

"I’ll scout around a bit and see what I can find," he said.

It was not until lunch was nearly over that she was able to detach her mind from the baby. Then she asked, "Oh, Peter, what happened with Commander Towers?"

"He’d got a draft operation order," he told her. "I suppose it’s confidential, so don’t talk about it. They want us to make a fairly long cruise in the Pacific. Panama, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, Dutch Harbor, and home, probably by way of Hawaii. It’s all a bit vague just at present."

She was uncertain of her geography. "That’s an awfully long way, isn’t it?"

"It’s quite a way," he said. "I don’t think we shall do it Dwight’s very much against going into the Gulf of Panama because he hasn’t got a clue about the minefields, and if we don’t go there that cuts off thousands of miles. But even so, it’s quite a way."

"How long would it take?" she asked.

"I haven’t worked it out exactly. Probably about two months. You see," he explained, "you can’t set a direct course, say for San Diego. He wants to keep the underwater time down to a minimum. That means we set course east on a safe latitude steaming on the surface till we’re two-thirds of the way across the South Pacific, and then go straight north till we come to California. It makes a dogleg of it, but it means less time submerged."

"How long would you be submerged, Peter?"

"Twenty-seven days, he reckons."

"That’s an awfully long time, isn’t it?"

"It’s quite long. It’s not a record, or anywhere near it. Still, it’s quite a time to be without fresh air. Nearly a month."

"When would you be starting?"

"Well, I don’t know that. The original idea was that we’d get away about the middle of next month, but now we’ve got this bloody measles in the ship. We can’t go until we’re clear of that."

"Have there been any more cases?"

"One more—the day before yesterday. The surgeon seems to think that’s probably the last. If he’s right we might be cleared to go about the end of the month. If not—if there’s another one—it’ll be sometime in March."

"That means that you’d be back here sometime in June?"

"I should think so. We’ll be clear of measles by the tenth of March whatever happens. That means we’d be back here by the tenth of June."

The mention of measles had aroused anxiety in her again. "I do hope Jennifer doesn’t get it."

They spent a domestic afternoon in their own garden. Peter started on the job of taking down the tree. It was not a very large tree, and he had little difficulty in sawing it half through and pulling it over with a rope so that it fell along the lawn and not on to the house. By teatime he had lopped its branches and stacked them away to be burned in the winter, and he had got well on with sawing the green wood up into logs. Mary came with the baby, newly wakened from her afternoon sleep, and laid a rug out on the lawn and put the baby on it. She went back into the house to fetch a tray of tea things; when she returned the baby was ten feet from the rug trying to eat a bit of bark. She scolded her husband and set him to watch his child while she went in for the kettle.

"It’s no good," she said. "We’ll have to have that playpen.

He nodded. "I’m going up to town tomorrow morning," he said. "We’ve got a date at the Navy Department, but after that I should be free. I’ll go to Myers’ and see if they’ve still got them there."

"I do hope they have. I don’t know what we’ll do if we can’t get one."

"We could put a belt round her waist and tether her to a peg stuck in the ground."

"We couldn’t, Peter!" she said indignantly, "She’d wind it round her neck and strangle herself!"

He mollified her, accustomed to the charge of being a heartless father. They spent the next hour playing with their baby on the grass in the warm sun, encouraging it to crawl about the lawn. Finally Mary took it indoors to bathe it and give it its supper, while Peter went on sawing up the logs.

He met his captain next morning in the Navy Department, and together they were shown into the office of the First Naval Member, who had a captain from the Operations Division with him. He greeted them cordially, and made them sit down. "Well now," he said. "You’ve had a look at the draft operation order that we sent you down?"

"I made a very careful study of it, sir," said the captain.

"What’s your general reaction?"

"Minefields," Dwight said. "Some of the objectives that you name would almost certainly be mined." The admiral nodded. "We have full information on Pearl Harbor and on the approaches to Seattle. We have nothing on any of the others."

They discussed the order in some detail for a time. Finally the admiral leaned back in his chair. "Well, that gives me the general picture. That’s what I wanted." He paused. "Now, you’d better know what this is all about.

"Wishful thinking," he observed. "There’s a school of thought among the scientists, a section of them, who consider that this atmospheric radioactivity may be dissipating—decreasing in intensity, fairly quickly. The general argument is that the precipitation during this last winter in the Northern Hemisphere, the rain and snow, may have washed the air, so to speak." The American nodded. "According to that theory, the radioactive elements in the atmosphere will be falling to the ground, or to the sea, more quickly than we had anticipated. In that case the ground masses of the Northern Hemisphere would continue to be uninhabitable for many centuries, but the transfer of radioactivity to us would be progressively decreased. In that case life—human life—might continue to go on down here, or at any rate in Antarctica. Professor Jorgensen holds that view very strongly."

Читать дальше