"Coming here?" he asked, surprised.

"Yes. They’ve got leave before they go off on some other trip. You don’t mind, do you?"

"Of course not. I hope it’s not going to be dull for him, though. What are you going to do with him all day?"

"I told him he could drive the bullock round the paddocks. He’s very practical."

"I could do with somebody to help feed out the silage," her father said.

"Well, I expect he could do that. After all, if he commands a nuclear-powered submarine he ought to be able to learn to shovel silage."

They went into the house. Later that night he told her mother about their visitor. She was properly impressed. "Do you think there’s anything in it?"

"I don’t know," he said. "She must like him all right."

"She hasn’t had a man to stay since that Forrest boy, before the war."

He nodded. "I remember. Never thought much of him. I’m glad that came to an end."

"It was his Austin-Healey," her mother remarked. "I don’t think she ever cared for him, not really."

"This one’s got a submarine," her father said helpfully. "It’s probably the same thing."

"He can’t take her down the road in that at ninety miles an hour." She paused, and then she said, "Of course, he must be a widower now."

He nodded. "Everybody says that he’s a very decent sort of chap."

Her mother said, "I do hope something comes of it. I would like to see her settled down, and happily married with some children."

"She’ll have to be quick about it, if you’re going to see that," remarked her father.

"Oh dear, I keep forgetting. But you know what I mean."

He came to her on Tuesday afternoon; she met him with the horse and buggy. He got out of the train and looked around, sniffing the warm country air. "Say," he said, "you’ve got some pretty nice country around here. Which way is your place?"

She pointed to the north. "Over there, about three miles."

"Up on that range of hills?"

"Not right up," she said. "Just a bit of the way up."

He was carrying a suitcase, and swung it up into the buggy, pushing it under the seat. "Is that all you’ve got?" she demanded.

"That’s right. It’s full of mending."

"It doesn’t look much. I’m sure you must have more than that."

"I haven’t. I brought everything there was. Honest."

"I hope you’re telling me the truth." They got up into the driving seat and started off towards the village. Almost immediately he said, "That’s a beech tree! There’s another!"

She glanced at him curiously. "They grow round here. I suppose it’s cooler on the hills."

He looked at the avenue, entranced. "That’s an oak tree, but it’s a mighty big one. I don’t know that I ever saw an oak tree grow so big. And there’s some maples!" He turned to her. "Say, this is just like an avenue in a small town in the States!"

"Is it?" she asked. "Is it like this in the States?"

"It certainly is," he said. "You’ve got all the trees here from the Northern Hemisphere. Parts of Australia I’ve see up till now, they’ve only had gum trees and wattles."

"They don’t make you feel bad?" she asked.

"Why, no. I just love to see these northern trees again."

"There are plenty of them round the farm," she said. They drove through the village, across the deserted bitumen road, and out upon the road to Harkaway. Presently the road trended uphill; the horse slowed to a walk and began to slog against the collar. The girl said, "This is where we get out and walk."

He got down with her from the buggy, and they walked together up the hill, leading the horse. After the stuffiness of the dockyard and the heat of the steel ships, the woodland air seemed fresh and cool to him. He took off his jacket and laid it in the buggy, and loosened the collar of his shirt. They walked on up the hill, and now a panorama started to unfold behind them, a wide view over the flat plain to the sea at Port Philip Bay ten miles away. They went on, riding on the flats and walking on the steeper parts, for half an hour. Gradually they entered a country of gracious farms on undulating hilly slopes, a place where well-kept paddocks were interspersed with coppices and many trees. He said, "You’re mighty lucky to have a home in country like this."

She glanced at him. "We like it all right. Of course, it’s frightfully dull living out here."

He stopped, and stood in the road, looking around him at the smiling countryside, the wide, unfettered views. "I don’t know that I ever saw a place that was more beautiful," he said.

"It is beautiful?" she asked. "I mean, is it as beautiful as places in America or England?"

"Why, sure," he said. "I don’t know England so well. I’m told that parts of that are just a fairyland. There’s plenty of lovely scenery in the United States, but I don’t know of any place that’s just like this. No, this is beautiful all right, by any standard in the world."

"I’m glad to hear you say that," she replied. "I mean, I like it here, but then I’ve never seen anything else. One sort of thinks that everything in England or America must be much better. That this is all right for Australia, but that’s not saying much."

He shook his head. "It’s not like that at all, honey. This is good by any standard that you’d like to name."

They came to a flat and, driving in the buggy, the girl turned into an entrance gate. A short drive led between an avenue of pine trees to a single-storey wooden house, a fairly large house painted white that merged with farm buildings towards the back. A wide verandah ran along the front and down one side, partially glazed in. The girl drove past the house and into the farmyard. "Sorry about taking you in by the back door," she said. "But the mare won’t stand, not when she’s so near the stable."

A farm hand called Lou, the only employee on the place, came to help her with the horse, and her father came out to meet them. She introduced Dwight all round, and they left the horse and buggy to Lou and went into the house to meet her mother. Later they gathered on the verandah to sit in the warm evening sun over short drinks before the evening meal. From the verandah there was a pastoral view over undulating pastures and coppices, with a distant view of the plain down below the trees. Again Dwight commented upon the beauty of the countryside.

"Yes, it’s nice up here," said Mrs. Davidson. "But it can’t compare with England. England’s beautiful."

The American asked, "Were you born in England?"

"Me? No. I was born Australian. My grandfather came out to Sydney in the very early days, but he wasn’t a convict. Then he took up land in the Riverina. Some of the family are there still." She paused. "I’ve only been home once," she said. "We made a trip to England and the Continent in 1948, after the Second War. We thought England was quite beautiful. But I suppose it’s changed a lot now."

She left the verandah presently with Moira to see about the tea, and Dwight was left on the verandah with her father. He said, "Let me give you another whisky."

"Why, thanks. I’d like one."

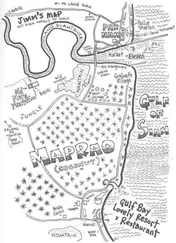

They sat in warm comfort in the mellow evening sun over their drinks. After a time the grazier said, "Moira was telling us about the cruise that you just made up to the north."

The captain nodded. "We didn’t find out much."

"So she said."

"There’s not much that you can see, from the water’s edge and through the periscope," he told his host. "It’s not as if there was any bomb damage, or anything like that. It all looks just the same as it always did. It’s just that people don’t live there any more."

"It was very radioactive, was it?"

Dwight nodded. "It gets worse the further north you go, of course. At Cairns, when we were there, a person might have lived for a few days. At Port Darwin nobody could live so long as that."

Читать дальше