Alex Adams

WHITE HORSE

A Novel

I wrote this for you, Bill.

“WHEN I WAKE, THE WORLD IS STILL GONE. ONLY FRAGMENTS REMAIN.”

DATE: THEN

Look at me: I don’t want my therapist to think I’m crazy. That the lie rolls off my tongue without tripping over my teeth is a miracle.

“I dreamed of the jar last night.”

“Again?” he asks.

The leather squeaks beneath my head when I nod.

“The exact same jar?”

“Always the same.”

There’s a scratching as he pushes his pen across the paper.

“Describe it for me, Zoe.”

We’ve done this a half dozen times, Dr. Nick Rose and I. My answer never changes, and yet I indulge him when he asks. Or maybe he indulges me. Me because I’m haunted by the jar, him because he has a boat to buy.

The couch cushions crease under me as I lean back and drink him in the way one drinks that first cup of coffee in the mornings. Small, savoring sips. He fills the comfortably worn leather chair. His body has buffed it to a gentle gleam that is soothing to the eye. His large hands are worn from work that doesn’t take place in this office. The too-short hair, easy to maintain. His eyes are dark like mine. His hair, too. There’s a scar on his scalp his gaze can’t possibly reach in the mirror, and I wonder if his fingers dance over it when he’s alone or if he’s even aware of its presence. His skin is tan; indoors is not his default. But where to put him? Maybe not a boat. Maybe a motorcycle. The idea of him straddling a motorcycle makes me smile on the inside. I keep it hidden there. If I let it creep to my lips, he’ll ask about that. And while I tell him all my thoughts, I don’t always share my secrets.

“Scorched cream. If it were a paint color, that’s what they’d call it. It’s like… it was made for me. When I reach out in the dream, there’s a perfectness to the angle of my arms as I try to grasp the handles. Did you ever have the one kid in school whose ears stuck out like this?” I sit straight, tuck my hair behind my ears, shove them forward at painful right angles.

His mouth twitches. He wants to smile. I can see the debate: Is it professional to laugh? Will she read it as sexual harassment? Laugh , I want to tell him. Please .

“I was that kid.”

“Really?”

“No.” His smile breaks free, and for a moment I forget the jar. It’s neither huge nor perfect, but he made it for me. I find myself filled with a million questions, each designed to probe him the way he searches me.

“Do you have a recurring dream?” I ask.

The smile melts away. “I don’t remember them. But we’re talking about you.”

Right. Don’t throw me a bone . “The jar, the jar. What else to tell you about the jar?”

“Are there any markings?”

I don’t need to stop and think; I know. “No. It’s pristine.” My shoulders ache with tension. “That’s all.”

“How does it make you feel?”

“Terrified.” I lean forward, elbows pressing a dent into my knees. “And curious.”

DATE: NOW

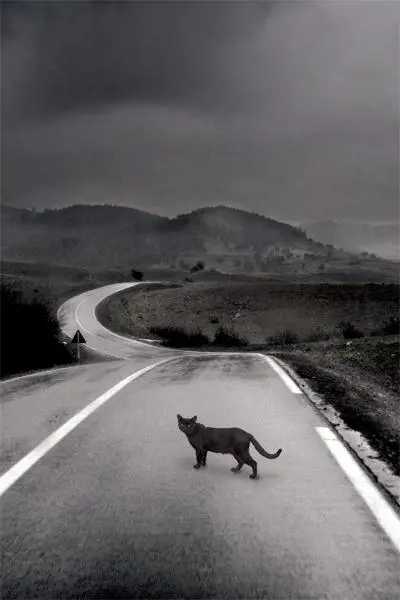

When I wake, the world is still gone. Only fragments remain. Pieces of places and people who were once whole. On the other side of the window, the landscape is a violent green, the kind you used to see on a flat-screen television in a watering hole disguised as a restaurant. Too green. Dense gray clouds banished the sun weeks ago, forcing her to watch us die through a warped, wet lens.

There are stories told among pockets of survivors that rains have come to the Sahara, that green now sprinkles the endless brown, that the British Isles are drowning. Nature is rebuilding with her own set of plans. Man has no say.

It’s a month until my thirty-first birthday. I am eighteen months older than I was when the disease struck. Twelve months older than when war first pummeled the globe. Somewhere in between then and now, geology went crazy and drove the weather to schizophrenia. No surprise when you look at why we were fighting. Nineteen months have passed since I first saw the jar.

I’m in a farmhouse on what used to be a farm somewhere in what used to be Italy. This is not the country where gleeful tourists toss coins into the Trevi Fountain, nor do people flock to the Holy See anymore. Oh, at first they rushed in like sickle cells forced through a vein, thick, clotted masses aboard trains and planes, toting their life savings, willing to give it all to the church for a shot at salvation. Now their corpses litter the streets of Vatican City and spill into Rome. They no longer ease their hands into La Bocca della Verità and hold their breath while they whisper a pretty lie they’ve convinced themselves is real: that a cure-all is coming any day now; that a band of scientists hidden away in some mountaintop have a vaccine that can rebuild us; that God is moments away from sending in His troops on some holy lifesaving mission; that we will be saved.

Raised voices trickle through the walls, reminding me that while I’m alone in the world, I’m not alone here.

“It’s the salt.”

“It’s not the fucking salt.”

There’s the dull thud of a fist striking wood.

“I’m telling you, it’s the salt.”

I do a mental tally of my belongings as the voices battle: backpack, boots, waterproof coat, a toy monkey, and inside a plastic sleeve: a useless passport and a letter I’m too chicken to read. This is all I have here in this ramshackle room. Its squalor is from before the end, I’ve decided. Poor housekeeping; not enough money for maintenance.

“If it’s not the salt, what is it?”

“High-fructose corn syrup,” the other voice says, with the superior tone of one convinced he’s right. Maybe he is. Who knows anymore?

“Ha. That doesn’t explain Africa. They don’t eat sweets in Timbuktu. That’s why they’re all potbelly skinny.”

“Salt, corn syrup, what does it matter?” I ask the walls, but they’re short on answers.

There’s movement behind me. I turn to see Lisa No-last-name filling the doorway, although there is less of her to fill it than there was a week ago when I arrived. She’s younger than me by ten years. English, from one of those towns that ends in -shire . The daughter of one of the men in the next room, the niece of the other.

“It doesn’t matter what caused the disease. Not now.” She looks at me through feverish eyes; it’s a trick: Lisa has been blind since birth. “Does it?”

My time is running out; I have a ferry to catch if I’m to make it to Greece.

I crouch, hoist my backpack onto my shoulders. They’re thinner now, too. In the dusty mirror on the wall, the bones slice through my thin T-shirt.

“Not really,” I tell her. When the first tear rolls down her cheek, I give her what I have left, which amounts to a hug and a gentle stroke of her brittle hair.

I never knew my steel bones until the jar.

The godforsaken jar.

DATE: THEN

My apartment is a modern-dayfortress. Locks, chains, and inside a code I have three chances to get right, otherwise the cavalry charges in, demanding to know if I am who I say I am. All of this is set into a flimsy wooden frame.

Eleven hours cleaning floors and toilets and emptying trash in hermetic space. Eleven hours exchanging one-sided small talk with mice. Now my eyes burn from the day, and I long to pluck them from their sockets and rinse them clean.

Читать дальше