He walked steadily until he arrived at the foot of the stepped plinth. For just a moment he thought of that other plinth, the one from the Black Dome that he had had brought back to Adamantinarx and enshrined.

Slowly, he paced the base’s periphery until he came upon that which he had hoped to find. He put his hand upon the rugose brick and felt its warmth and then, suddenly, it opened a piercingly blue eye and stared up at him. For a moment their gaze met and then he sighed and stood up. He looked into the heavens and saw the equally blue star—the star they called Zimiah, the Gate—and knew what he would have to do. The statue would have to come down and the bricks of its base—this brick in particular—would have to be resurrected. That much, he knew, he owed his lord.

This book was, by any measure, an ambitious undertaking for me. There was not one moment during its creation that I was not certain I had made a terrible mistake in breaking away from painting and drawing to attempt it. During the arduous process of writing, however, I was bolstered by people both alive and dead, without whom I could never have finished the task. First and foremost among them was my wife, Shawna McCarthy, who told me more times than I can count that this was a journey that I was capable of completing. This book could never have been finished without her wisdom and unflagging encouragement, and my gratitude to her is total.

I must also thank my wonderful agent and friend, Russell Galen, for his continued support and valuable comments. Thanks must also go to my editor, Pat LoBrutto, who understood this project from the start and whose humor and insights into matters both heavenly and infernal were always welcome.

Thanks also to my great friend, TyRuben Ellingson, for his deep understanding of the labyrinth that is my creative mind.

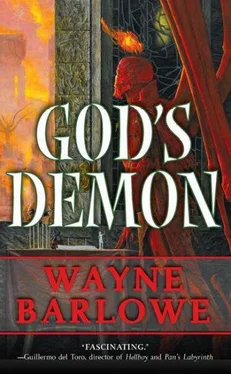

God’s Demon would not exist but for the inspiration provided me by John Milton’s Paradise Lost. That work of genius, arguably the greatest poem written in the English language, set me on the path to first visualize Hell in artwork and then in writing. Like Dante’s Virgil, Milton’s spirit was a constant, guiding companion.

John Dee’s Complete Enochian Dictionary provided me with the basis for the language used throughout this book in both the pure “angelic” form and the somewhat corrupted “demonic” form. Dr. Dee’s unique work was derived from conversations he had in 1581 with two angels and, therefore, seemed to me authoritative.

To enrich your reading of God’s Demon with many of the images of Hell that I have created, please visit www.godsdemon.com.

Barlowe’s Inferno

Barlowe’s Inferno — (from Barlowe’s Inferno — acrylic on panel) — The unpredictable chaos of Hell is present even in the most advanced of its cities. Dis, like all of its sister cities, suffers from wrenching, deafening upheavals that tear through the city breaking away and sending archi-organic buildings high into the air. These float about, sometimes leaving the city’s wards entirely, making their way into the darkness of the Wastes where they are never seen again. Do they eventually land only to be in habited by Salamandrine Men or Abyssals? Few have ever found out and fewer still have survived to tell of it.

It was impossible for me to resist putting myself in the Hell that I created. Of course, I could not appear inappropriately whole and so, much like the demons themselves, I took up hook and tong and made myself suitable for place. When in Rome…

What Remains

What Remains — (unpublished — acrylic on Gessoboard) — As much as Hell is a place of unrelenting horror and savagery it is, too, a place of sadness. What else could a being once of Heaven feel than sadness finding itself in such an environment? And what more poignant, precious reminder of its former existence could it possess after its Fall than one of its own charred feathers?

Executing Hell paintings can be an exercise in pacing. After spending months completing very complex, detailed paintings I tend to gravitate towards simpler, more iconic compositions. This serves both to recharge my batteries and to force me to make more concise statements. To me the most difficult part of this painting’s concepting was whether or not to add a question mark after the title.

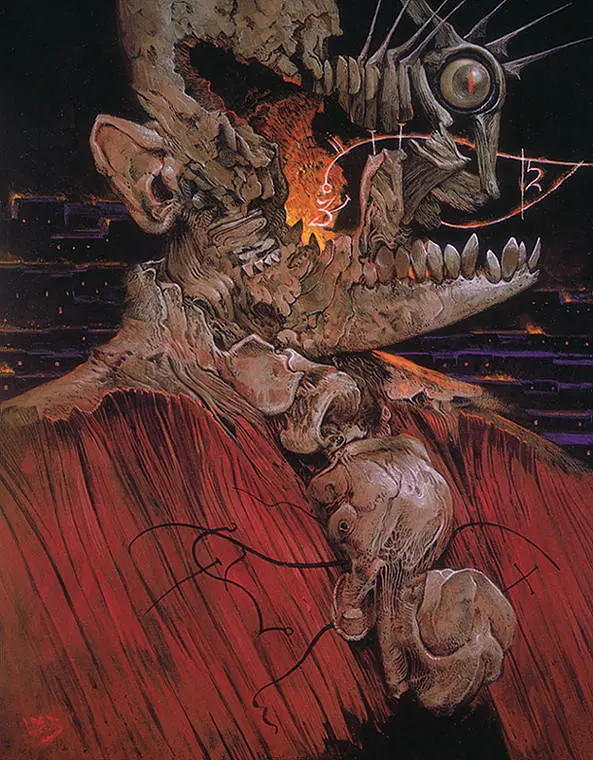

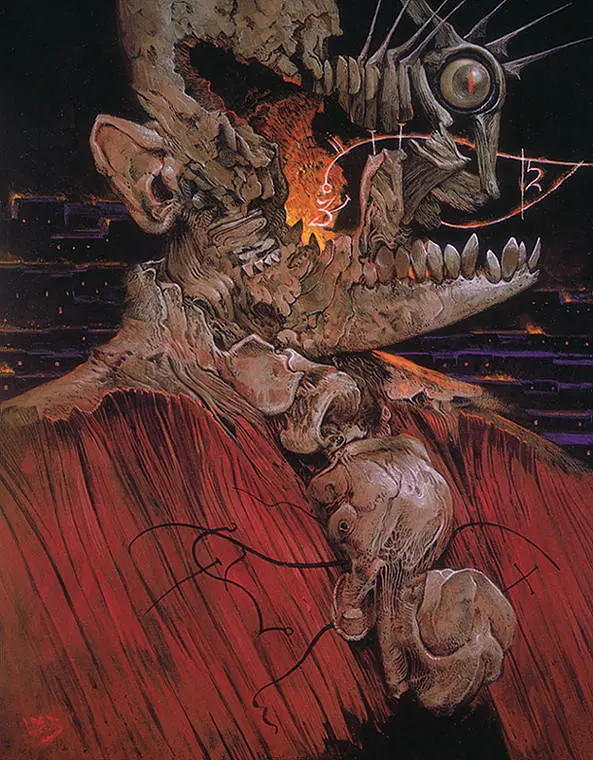

Sargatanas

Sargatanas — (from Barlowe’s Inferno , acrylic on ragboard) — A former seraph and now a Brigadier General and Demon Major of enormous power, Sargatanas was a hero in Lucifer’s War with Heaven. Since his Fall, he has established himself as one of the few demons capable of rivaling the Prince for control of Hell. GOD’S DEMON is his story.

There’s a lot of improvisation in this piece. I wanted to leave some of the organically flowing elements, especially around his metamorphic head, to chance, to let my paintbrush do the thinking, as it were. And I also wanted to let the paint, itself, flow a little more freely to enhance the sense of dynamism this character has always had in my mind. Some have criticized my decision to go in a more “painterly” direction with the Hell pieces. To me it is not only a natural evolution for a painter to become freer and more expressive, but, in this case, the milieu does afford one the perfect opportunity to be a bit more evocative. It’s a case of adapting oneself to the subject matter.

Sargatanas Descending

Sargatanas Descending — (from Barlowe’s Inferno — acrylic on ragboard) — Like all Demons Major, Sargatanas is a metamorphic being. Because distances between cities in Hell are considerable — determined for the most part by where the most influential demons Fell — the need to travel quickly between them is rare. Nonetheless, demons like Sargatanas are capable of sprouting great fan-like wings that bear some resemblance to their former seraphic or cherubic wings for just such journeys. Nearly all semblance of anthropomorphism is lost in this demonic form. Here potent glyphs stream away from the wings’ trailing edges, glyphs that not only keep the demon aloft but also delineate territories and can carry commands to nearby airborne troops.

Even though he worked roughly two hundred years ago there is yet a transcendent majesty to William Blake’s vivid, mystical painting’s and etchings. His idiosyncratic style is still fresh and captivating and this painting is something of an homage to him. Blake was one of the most interesting artists and poets of his day and I would be remiss in not mentioning that he, too, fell under the spell of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, the single greatest influence on my Hell work.

Sargatanas Mutatis

Eligor

The Examination

The Examination — (from Barlowe’s Inferno — acrylic on ragboard) — While souls are treated as a resource by demons in an unthinkable number of ways in Hell, a true understanding of them as once-living organisms on a physical level is absent. The fact that Lucifer went to war in large part because of them has created a curiosity that many demons find irresistible. The inspiration for this painting is fairly obvious: all of those great Flemish paintings of medical examinations, of doctors gathered around splayed-out corpses. Nearly all of the look of the demons was improvised invention. I had a rough to work from and then, brush in hand, “grew” the figures on the board with layers of detail. I often do detailed drawings before putting paint on the palette but this was not the case with this painting. I wanted to enjoy the act of creating these inquisitive demons and felt that being too slavish to a sketch might make them less lively.

Читать дальше