“I do. You’re getting old.” May laughed, hoping Molly would join her.

Molly did laugh, though it was not quite the joyous sound May wanted.

“Let’s fix something nice for lunch,” May finally said. “Something Gretchen will like.”

It was the scent of a roast stewing in the pot that pulled Gretchen of out her slumber. She woke in a daze of half-remembered moonlight. It took her several minutes to assess her surroundings. White walls, wooden bedposts, ancient dresser with two handles missing: finally she recalled her whereabouts. Safe, she exhaled relief. Shakily, she pulled loose trousers to her hips and tied them. She lifted a worn shirt from the back of a chair and buttoned it, though her fingers clumsily left half of it undone. Warily, still sensing her environment more than seeing it, she slipped out of the bedroom and made her way down the stairs.

Her sisters greeted her as usual.

“Good morning, Gretchen. How do you feel?” May was always the first to question her well-being.

“Hey, sis,” Molly said.

“What do I smell?” Gretchen asked in response.

Her sisters were never quite sure if they were talking to wolf or woman on this, the day after the full of the moon. Appearances were deceptive, and May more than Molly understood that the wolf often lingered much longer in spirit than it did in body.

“Meat. I made stew for lunch,” May said as she watched Gretchen’s nostrils flare.

The wolf had left its mark as time passed by. After ten years of this, Gretchen no longer had a taste for much fruit, nor certain vegetables. Leafy salads were fine most of the time, and certain berries, but beans, tomatoes, and onions were out of the question. She drank water, milk, and occasionally coffee, but not tea and never soda. Meat was the staple of her diet, but May could live with that as long as Gretchen didn’t start asking for it raw.

As she ate, Gretchen’s thoughts slowly settled into more familiar patterns. Something was different this morning, however. Some memory, some unfamiliar disturbance tugged at her. She touched it, circled it as the wolf would, tried to catch the scent of it, but to no avail. What happened last night? She felt an ache she did not recognize.

“What is it?” May asked when she noticed Gretchen staring absently at the window.

Gretchen blinked her eyes. “Nothing. Something. I don’t know. Last night. I don’t know.”

She never spoke of the night. May, concerned, put a hand on her sister’s forehead. “Nothing seemed amiss when we found you. You sure you’re okay?”

“Yeah. I’m fine. Don’t worry,” Gretchen smiled, a bit more like her usual self.

“Well, let me know if you need anything,” May said.

“I will.”

After she finished, Molly washed her hair and helped her dress in more reasonable clothes. By then, Gretchen felt almost human. Molly nattered on about nothing while May swept the floors. Gretchen caught herself gazing toward the dark forest and shook her head. Whatever was haunting her must not be brought into the light.

What the wolf knew as it ran through the forest was like a distant dream to Gretchen, one that she always gladly let fade the following day. She despised everything about the wolf and what it had done to her. She separated it, culled it from the experience of her own life, pretended that she and it were two distinct beings. They would never meet, nor know of each other’s cares. Yet, that night, as she curled up in her bed, images passed behind her closed eyes: a cabin, a cage, a shape inside it. Scent returned, new blood on old, musk, hair, and fear.

Gretchen sat upright in horror as it came to her. The wolf had seen a ravaged woman in a cage, and she was alive.

“Holy shit,” Gretchen whispered into the room.

Sleep did not come easily that night and wouldn’t have at all had she not still been exhausted from the night before. Dreams stirred like leaves on the forest floor, but she could not catch them. They passed, like summer does into autumn.

For days she was restless. Alone when her sisters worked, she paced the halls, ate little and worried at the wolf’s memory. There was no way to know what was real and what was not. The human mind must categorize, put color to objects, know distance in feet and yards. The wolf-mind knew shapes, sensations, the taste of air. She felt dirty, touching these things. Shame at what she was overpowered her at times, bending her knees, crawling along her skin like an insect. She rubbed at her arms, shivering, and tried to brush it off. She almost did cut off her hair, as though by doing so it would distance her from the wolf. She warred with it, she did not want to know the wolf’s mind, and yet she must comprehend these visions. If this thing she thought she’d seen was real, if there was a woman in a cage, she must do something. She could not leave her out there alone.

There was something else come through from that eerie night. A longing, a connection almost, that Gretchen could not name.

“That’s it,” she said at last to no one. “I’ve got to go back.”

The next day her sisters both worked early. May’s shift began at nine, Molly’s at one. When they were gone, Gretchen left a note on the table, packed food and water into a bag and left. She did not know when she would be home; she could not guess how far away the cabin was. Her sisters would worry if she did not return before them, but she could not bring herself to tell them of her plan. There was no way to explain it, this thing she saw out of the wolf’s eyes.

In the woods, she stopped. Each direction seemed as viable as the other. Gretchen realized with a slow burn of horror that she would never navigate this place on her own. But for the image of that woman, she would have turned away then and given up, gone back to the house, done anything but what she must do now.

Gretchen breathed deeply and focused, trying to invoke the monster that slept inside her. Down deep she went into the primal source of mind, where flesh means less and instinct is all. She moved, step by step, until her feet became sure and led her onwards toward the stream. Gnats flew into her eyes, things scurried in the brush and overhead, a bird called out in warning. She grew hungry, she gnawed on bread and chicken left over from the last evening’s meal. Hours passed and she barely noticed. She was only half-human now. The wolf led her through the wood.

She stopped in a copse as fear gripped her. Gretchen neither saw nor heard anything unusual, but she heeded the feeling and kept still for several long moments. In the quiet, a faint whimpering and whining—the sound a dog would make if it were pleading—became audible through the trees.

Gretchen pressed on, urgency driving her steps. Fully herself now, she was less cautious than she should have been; sticks snapped underfoot and branches cracked as she pushed them out of her way.

She tracked the sound of the weeping animal to the clearing. She stopped at its edge and ducked down behind a young maple surrounded by brush. Twigs caught in her hair and snagged on her shirt; she ignored them. From behind the tangle of branches she saw the cabin, forlorn and yet obviously tenanted, for there was freshly cut wood stacked beside it and litter strewn around the door. She registered the dwelling, but it was not this that held her attention. In the scuffed and flattened ground before it, she saw what had been making the noise.

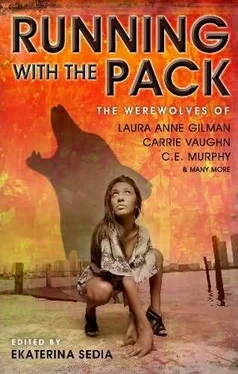

Silent now, hackles raised, a crushingly pathetic wolf was held in a cage. It was an ancient construction of black iron, much like those used in old traveling circus shows. In the advertisements, they rose up from the backs of colorful wagons in a merry display meant to arouse excitement and draw unwary customers in. The reality of the device repulsed her. The wolf, sensing her presence, turned toward her. Eyes met eyes. Gretchen’s breath caught in her throat.

Читать дальше