And that was why the duty was a burden. Because to be available for the aliens while they made the repairs—to play liaison (their word)—meant putting off the moment of joyous union again. And again. To have been so close, and then so far, and then so close again—

The agony of anticipation, and the fear that it would be snatched from him again, was a form of torture.

A’lees came outside of the alien skiff in her pressure carapace and sat in its water-poisoned circle with her forelimbs wrapped around her drawn-up knees, talking comfortably to Stormchases. She said she was a female, a Mother. But that Mothers of her kind were not so physically different from the males, and that even after they Mated, males continued to go about in the world as independent entities.

“But how do they pass their experiences on to their offspring?” Stormchases asked.

A’lees paused for a long time.

“We teach them,” she said. “Your children inherit your memories?”

“Not memories,” he said. “Experiences.”

She hesitated again. “So you become a part of the Mother. A kind of… symbiote. And your offspring with her will have all of her experiences, and yours? But… not the memories? How does that work?”

“Is knowledge a memory?” he asked.

“No,” she said confidently. “Memories can be destroyed while skills remain… Oh. I think… I understand.”

They talked for a little while of the structure of the nets and the Mothers’ canopies, but Stormchases could tell A’lees was not finished thinking about memories. Finally she made a little deflating hiss sound and brought the subject up again.

“I am sad,” A’lees said, “that when we have fixed our sampler and had time to arrange a new mission and come back, you will not be here to talk with us.”

“I will be here,” said Stormchases, puzzled. “I will be mated to the Mothergraves.”

“But it won’t be”—whatever A’lees had been about to say, the translator stammered on it; she continued—“the same. You won’t remember us.”

“The Mothergraves will,” Stormchases assured her.

She drew herself in a little smaller. “It will be a long time before we return.”

Stormchases patted toward the edge of the burn zone. He did not let his manipulators cross it, though. Though he would soon enough lose the use of his manipulators to atrophy, he didn’t feel the need to burn them off prematurely. “It’s all right, A’lees,” he said. “We will remember you by the scar.”

Whatever the sound she made next meant, the translator could not manage it.

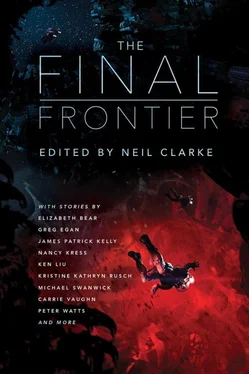

DIVING INTO THE WRECK

KRISTINE KATHRYN RUSCH

The award-winning “Diving into the Wreck” novella marked the first step in a large journey for New York Times bestselling writer Kristine Kathryn Rusch. She’s written many other award-winning novellas in the series, as well as the novels Diving into the Wreck, City of Ruins, Boneyards, Skirmishes, The Falls , and The Runabout . The next novel, Searching For The Fleet , will appear in September 2018. She’s working hard on the ninth and tenth novels in the series. When she finishes those, she’ll return to her massive Retrieval Artist universe. A eight-book saga in that universe has just been released in a single ebook boxed set—almost 2,000 pages long. She’s a Hugo Award-winning editor and writer, who has been nominated for most of the awards in the sf and mystery fields. She writes under several pen names as well. The public ones are Kristine Grayson and Kris Nelscott. To find out more about her work go to kriswrites.com . To find out more about Diving , go to divingintothewreck.com .

We approach the wreck in stealth mode: lights and communications array off, sensors on alert for any other working ship in the vicinity. I’m the only one in the cockpit of the Nobody’s Business . I’m the only one with the exact coordinates.

The rest of the team sits in the lounge, their gear in cargo. I personally searched each one of them before sticking them to their chairs. No one, but no one, knows where the wreck is except me. That was our agreement.

They hold to it or else.

We’re six days from Longbow Station, but it took us ten to get here. Misdirection again, although I’d only planned on two days working my way through an asteroid belt around Beta Six. I ended up taking three, trying to get rid of a bottom-feeder that tracked us, hoping to learn where we’re diving.

Hoping for loot.

I’m not hoping for loot. I doubt there’s something space-valuable on a wreck as old as this one looks. But there’s history value, and curiosity value, and just plain old we-done-it value. I picked my team with that in mind.

The team: six of us, all deep-space experienced. I’ve worked with two before—Turtle and Squishy, both skinny space-raised women who have a sense of history that most out here lack. We used to do a lot of women-only dives together, back in the beginning, back when we believed that sisterhood was important. We got over that pretty fast.

Karl comes with more recommendations than God; I wouldn’t’ve let him aboard with those rankings except that we needed him—not just for the varied dives he’s gone on, but also for his survival skills. He’s saved at least two diving-gone-wrong trips that I know of.

The last two—Jypé and Junior—are a father-and-son team that seem more like halves of the same whole. I’ve never wreck dived with them, though I took them out twice before telling them about this trip. They move in synch, think in synch, and have more money than the rest of us combined.

Yep, they’re recreationists, but recreationists with a handle: their hobby is history, their desires—at least according to all I could find on them—to recover knowledge of the human past, not to get rich off of it.

It’s me that’s out to make money, but I do it my way, and only enough to survive to the next deep space trip. I don’t thrive out here, but I’m addicted to it.

The process gets its name from the dangers: in olden days, wreck diving was called space diving to differentiate it from the planet-side practice of diving into the oceans.

We don’t face water here—we don’t have its weight or its unusual properties, particularly at huge depths. We have other elements to concern us: No gravity, no oxygen, extreme cold.

And greed.

My biggest problem is that I’m land-born, something I don’t confess to often. I spent the first forty years of my life trying to forget that my feet were once stuck to a planet’s surface by real gravity. I even came to space late: fifteen years old, already land-locked. My first instructors told me I’d never unlearn the thinking real atmosphere ingrains into the body.

They were mostly right; land pollutes me, takes out an edge that the space-raised come to naturally. I gotta consciously choose to go into the deep and dark; the space-raised glide in like it’s mother’s milk. But if I compare myself to the land-locked, I’m a spacer of the first order, someone who understands vacuum like most understand air.

Old timers, all space-raised, tell me my interest in the past comes from being land-locked. Spacers move on, forget what’s behind them. The land-born always search for ties, thinking they’ll understand better what’s before them if they understand what’s behind them.

I don’t think it’s that simple. I’ve met history-oriented spacers, just like I’ve met land-born who’re always looking forward.

It’s what you do with the knowledge you collect that matters and me, I’m always spinning mine into gold.

So, the wreck.

I came on it nearly a year before, traveling back from a bust I’d got suckered into with promise of glory. I was manually guiding my single-ship, doing a little mapping to pick up some extra money. They say there aren’t any undiscovered places any more in this part of our galaxy, just forgotten ones, and I think that’s true.

Читать дальше