Not that there aren’t difficulties, of course. It’s disconcerting to go up on the observation deck. Most of the exotics remain, blooming in wild profusion, but a good chunk of the hull has disappeared. The effect is that anything up there—flowers, bench, people—is drifting through naked space, held together only by the gravity we exert on each other. I don’t understand how we can breathe up there; surely the air is gone. There are a lot of things I don’t understand now, but I accept them.

The wardroom is mostly intact, except that you have to stoop to go through the door to the galley, which is only about two feet tall, and Ajit’s bunk has disappeared. We manage fine with two bunks, since I sleep every night with Ajit or Kane. The terminals are intact. One of them won’t display anymore, though. Ajit has used it to hold a holo he programmed on a functioning part of the computer and superimposed over where the defunct display stood. The holo is a rendition of a image he showed me once before, of an Indian god, Shiva.

Shiva is dancing. He dances, four-armed and graceful, in a circle decorated with flames. Everything about him is dynamic, waving arms and kicking uplifted leg and mobile expression. Even the flames in the circle dance. Only Shiva’s face is calm, detached, serene. Kane, especially, will watch the holo for hours.

The god, Ajit tells us, represents the flow of cosmic energy in the universe. Shiva creates, destroys, creates again. All matter and all energy participate in this rhythmic dance, patterns made and unmade throughout all of time.

Shadow matter—that’s what Kane and Ajit are working on. I remember now. Something decoupled from the rest of the universe right after its creation. But shadow matter, too, is part of the dance. It exerted gravitational pull on our ship. We cannot see it, but it is there, changing the orbits of stars, the trajectories of lives, in the great shadow play of Shiva’s dancing.

I don’t think Kane, Ajit, and I have very much longer. But it doesn’t matter, not really. We have each attained what we came for, and since we, too, are part of the cosmic pattern, we cannot really be lost. When the probe goes down into the black hole at the core, if we last that long, it will be as a part of the inevitable, endless, glorious flow of cosmic energy, the divine dance.

I am ready.

SLOW LIFE

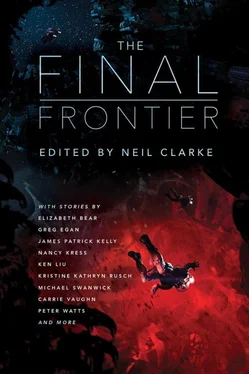

MICHAEL SWANWICK

Michael Swanwick published his first story in 1980, making him one of a generation of new writers that included Pat Cadigan, William Gibson, Connie Willis, and Kim Stanley Robinson. In the third of a century since, he has been honored with the Nebula, Theodore Sturgeon, and World Fantasy Awards and received a Hugo Award for fiction in an unprecedented five out of six years. He also has the pleasant distinction of having lost more major awards than any other science fiction writer.

“It was the Second Age of Space. Gagarin, Shepard, Glenn, and Armstrong were all dead. It was our turn to make history now.”

–

The Memoirs of Lizzie O’Brien

The raindrop began forming ninety kilometers above the surface of Titan. It started with an infinitesimal speck of tholin, adrift in the cold nitrogen atmosphere. Dianoacetylene condensed on the seed nucleus, molecule by molecule, until it was one shard of ice in a cloud of billions.

Now the journey could begin.

It took almost a year for the shard of ice in question to precipitate downward twenty-five kilometers, where the temperature dropped low enough that ethane began to condense on it. But when it did, growth was rapid.

Down it drifted.

At forty kilometers, it was for a time caught up in an ethane cloud. There it continued to grow. Occasionally it collided with another droplet and doubled in size. Until finally it was too large to be held effortlessly aloft by the gentle stratospheric winds.

It fell.

Falling, it swept up methane and quickly grew large enough to achieve a terminal velocity of almost two meters per second.

At twenty-seven kilometers, it passed through a dense layer of methane clouds. It acquired more methane, and continued its downward flight.

As the air thickened, its velocity slowed and it began to lose some of its substance to evaporation. At two and half kilometers, when it emerged from the last patchy clouds, it was losing mass so rapidly it could not normally be expected to reach the ground.

It was, however, falling toward the equatorial highlands, where mountains of ice rose a towering five hundred meters into the atmosphere. At two meters and a lazy new terminal velocity of one meter per second, it was only a breath away from hitting the surface.

Two hands swooped an open plastic collecting bag upward, and snared the raindrop.

“Gotcha!” Lizzie O’Brien cried gleefully.

She zip-locked the bag shut, held it up so her helmet cam could read the barcode in the corner, and said, “One raindrop.” Then she popped it into her collecting box.

Sometimes it’s the little things that make you happiest. Somebody would spend a year studying this one little raindrop when Lizzie got it home. And it was just Bag 64 in Collecting Case 5. She was going to be on the surface of Titan long enough to scoop up the raw material of a revolution in planetary science. The thought of it filled her with joy.

Lizzie dogged down the lid of the collecting box and began to skip across the granite-hard ice, splashing the puddles and dragging the boot of her atmosphere suit through the rivulets of methane pouring down the mountainside. “I’m sing-ing in the rain.” She threw out her arms and spun around. “Just sing-ing in the rain!”

“Uh… O’Brien?” Alan Greene said from the Clement . “Are you all right?”

“Dum-dee-dum-dee-dee-dum-dum, I’m… some-thing again.”

“Oh, leave her alone.” Consuelo Hong said with sour good humor. She was down on the plains, where the methane simply boiled into the air, and the ground was covered with thick, gooey tholin. It was, she had told them, like wading ankle-deep in molasses. “Can’t you recognize the scientific method when you hear it?”

“If you say so,” Alan said dubiously. He was stuck in the Clement , overseeing the expedition and minding the website. It was a comfortable gig —he wouldn’t be sleeping in his suit or surviving on recycled water and energy stix—and he didn’t think the others knew how much he hated it.

“What’s next on the schedule?” Lizzie asked.

“Um… Well, there’s still the robot turbot to be released. How’s that going, Hong?”

“Making good time. I oughta reach the sea in a couple of hours.”

“Okay, then it’s time O’Brien rejoined you at the lander. O’Brien, start spreading out the balloon and going over the harness checklist.”

“Roger that.”

“And while you’re doing that, I’ve got today’s voice-posts from the Web cued up.”

Lizzie groaned, and Consuelo blew a raspberry. By NAFTASA policy, the ground crew participated in all webcasts. Officially, they were delighted to share their experiences with the public. But the VoiceWeb (privately, Lizzie thought of it as the Illiternet) made them accessible to people who lacked even the minimal intellectual skills needed to handle a keyboard.

“Let me remind you that we’re on open circuit here, so anything you say will go into my reply. You’re certainly welcome to chime in at any time. But each question-and-response is transmitted as one take, so if you flub a line, we’ll have to go back to the beginning and start all over again.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Consuelo grumbled.

“We’ve done this before,” Lizzie reminded him.

“Okay. Here’s the first one.”

Читать дальше