“Yes, sir. The arrival matrix data’s on the console?”

“Ready and waiting.”

After two years together on the Francis Drake their routine was well practiced. He passed along the bridge’s upper walkway, paying only cursory attention to the displays and consoles that monitored the ship’s systems, nodding to the crewmates who looked up from their work, and arrived at the hatchway leading down to the navigator station.

M-drive navigation was a one-person booth isolated from the rest of the bridge. He settled into the couch, belted in, and activated the console. Monitors, scanners, processors lit up, casting a cool glow and humming comfortably. It was his own realm—quiet, secure, and powerful. Here, he controlled the equipment that could propel the ship light-years across space.

He clipped his comm piece over his ear and called up the navigation data, destination, and optimum window of arrival. With the ease of habit, he started the process that would identify the departure matrix for the most efficient jump to the designated arrival matrix.

Departure matrices flashed on the holographic display in unfamiliar hues. He frowned, reviewed the data, then cleared the equations. He had time; he’d simply run the calculations over again.

If he weren’t entirely clear on which matrix they left from and where they were arriving, the ship would break apart as it tried to make the crossing. An anomaly in the possible departure matrices made him pause. If he wasn’t certain about a matrix, he rejected it.

He’d never failed to find a departure matrix before. The Universe was massive and diverse; a solution could always be found. But this time they were all mouths, ready to swallow him, spitting out the wrong colors. The numbers cycled and showed him a void.

Except one. There it was, the solution. The matrix that would carry them safely away from this hole in space. He entered it, and the numbers flashed red.

Captain Scott said over the comm, “Greenau, do you have our heading?”

“Yes, sir. Departure matrix data transferred.”

A silence answered him. The workings of the ship hummed and murmured.

“Greenau, send those coordinates again, please.”

He did, with a touch of frustration.

“We can’t follow that heading, Lieutenant. Those coordinates are inside the hull of the ship.”

Of course not, the M-drive would push the ship into itself, making for one hell of an explosion. But Mitchell couldn’t ignore the numbers.

“It’s the only one, Captain.” All the other colors were wrong.

“Mitchell, are you all right?”

“There aren’t any other matrices. The space here is wrong. The colors are wrong.”

“Oh my God—”

They didn’t know it, they couldn’t see what he saw. He had to save them.

He’d fought as every crewmember on the bridge tried to stop him, because he thought he was saving them. That he could see something no one else could see. It never occurred to him that he’d gone mad. They’d seen it instantly—everyone knew what could happen to navigators, they all knew the symptoms. Still, he’d managed to get to the helm and punch in the drive protocol with the faulty departure matrix still entered—

They should have killed him before letting him get that far. They stopped short because he was theirs.

Parts of three levels ripped open instantly, spilling the ship’s guts to the void. Captain Scott managed to cut all the ship’s power, deactivating the drive before the ship was destroyed completely. The ship’s medics sedated Mitchell. The accident had killed twenty people, a third of the crew. Through sheer, stubborn heroism, Scott and the remaining crew patched up the ship and managed to fly to Law, the closest outpost. There, Lieutenant Mitchell Greenau could be deposited with people who might be able to explain what had gone wrong with his mind.

Head bowed, Mitchell knelt on the floor below the window as Doctor Keesey explained.

“The dysfunction usually develops gradually. The patient experiences memory loss, synesthesia, schizophrenia, dystonia, ataxia—any number of neurological anomalies. The captain of the ship will take a navigator off duty at the first signs. A sudden, catastrophic episode like yours is very rare.”

Who had died? He wanted to ask, but he doubted Keesey would know. Twenty names were too many to remember. But Mitchell would have to learn someday who among his friends and colleagues he had killed.

“You saw the right numbers, like you always saw,” Keesey said. “But your mind showed you something else.”

“Captain Scott didn’t want me to know what happened.”

“Because she knew it wasn’t your fault. It’s a terrible memory. I’m sorry.”

A memory that, for all he had struggled to reclaim it, now felt pristine, nestled in the center of his mind.

Mitchell felt calm now. Dalton stood nearby, and Keesey knelt beside him; both were watchful, like they expected him to break, or burst, or something, with the knowledge he had found.

Keesey finally said, “Mitchell, how do you feel?”

He despised that question.

He chuckled a little. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry—”

“Mitchell—”

He could look up, and even at this awkward angle he could see lights on the opposite curve of the station, the blackness of the shadows. The beauty was an ache in his gut. That he could still feel that beauty startled him. “Don’t isolate us from what makes us happy. We kill ourselves trying to get back to it.”

“Are you ready to come back to the ward?”

He climbed to his feet, using the wall as a prop. He looked out the window again to the stark vastness of even this little corner of space. “Just another minute, Doctor.”

They waited for him.

When Mitchell finally returned to the common room, Dora wasn’t there. She’d made an escape attempt and had been sedated.

Jaspar was at his usual table, working his word puzzles on his handheld. Mitchell found what had happened to him: he’d tried to close his head in a bulkhead door. No one knew why. The trauma team got to him quickly, and he’d survived, somehow. People were resilient.

Sonia was also present, humming, her eyes closed. Mitchell sat across from her.

He placed a player with earpieces in front of her. She stopped humming. She looked at him, her gaze narrowed and confused.

“It’s yours.”

Her hands trembling, she reached for the headphones. They skittered away from her fingertips the first time, but she caught them, slapping her hand to the table. Then she hooked on the earpieces.

Mitchell had gotten Keesey to give him records of Sonia’s musical vocabulary, all the pieces of music she’d been known to speak of. He convinced the doctors to let her have the player.

She touched the play key. Her face tightened, an expression of anxious disbelief. Then tears slipped down her cheeks. Mitchell heard the music, a faint buzzing through the earpieces, and his fists clenched nervously. He thought she would smile. He wanted her to smile.

Then she did smile, though she still didn’t relax, and Mitchell realized that she was concentrating on the music with every muscle she had. She met his gaze, and he thought she looked happy.

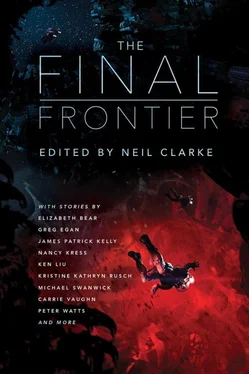

THE WRECK OF THE GODSPEED

JAMES PATRICK KELLY

James Patrick Kelly has won the Hugo, Nebula and Locus awards. He has written novels, short stories, essays, reviews, poetry, plays and planetarium shows. His most recent publications are the novel Mother Go (2017), an audiobook original from Audible and the collection The Promise of Space (2018) from Prime Books. In 2016, Centipede Press published a career retrospective Masters of Science Fiction: James Patrick Kelly . His fiction has been translated into eighteen languages. He writes a column on the internet for Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine and is on the faculty of the Stonecoast Creative Writing MFA Program at the University of Southern Maine. Find him on the web at www.jimkelly.net .

Читать дальше