"Fanatics," said Anton. "I do hope you notice that I didn't add any wisecrack such as 'and coming from Victor Cachat, that's saying something.' "

"Very funny. The problem is that tepid, wishy-washy people like you, whose commitment to anything beyond immediate personal matters is like mashed potatoes, just don't grasp all the fine distinctions between 'fanaticism' and 'fervor' and 'zeal.' "

Victor took a deep, slow breath. Not to control any anger—by now, the banter between him and Anton produced nothing more intense than occasional irritation—but to give himself time to try to figure out how to explain his concern.

"You just . . . don't really know, Anton. That's not a criticism, it's just an observation. From the time you were a kid, you lived in a world with wide horizons."

Zilwicki snorted. "Not usually the way the highlands of Gryphon are described!"

"Try growing up in a Dolist slum in Nouveau Paris. Trust me, Anton. The difference is huge. I'm not talking in terms of any scale of misery, mind you. I'm simply talking in terms of how narrow a view of the universe you're provided with. When I entered StateSec Academy, for all practical purposes I had no real knowledge of the universe beyond what I'd grown up with. Which wasn't much, believe me. That's . . ."

He paused for a moment. "I know a lot of people think I'm inclined toward zealotry. I suppose that's fair enough. What has changed, as the years have passed, is that my understanding of the universe has become . . . well, very large. So while I still retain the fundamental beliefs I had as a teenager, I can now put those beliefs in a much better context. I can, for instance, spend hours discussing politics with Web Du Havel—as I have, any number of times—listening to his basically conservative views without automatically dismissing those views as the self-serving prattle of an elitist."

Anton smiled. "Web just doesn't fit that pigeonhole, does he?"

"No, he doesn't. And while I still disagree with Web—for the most part, though by no means always—I do understand why he thinks the way he does. To put it another way, my view of things hasn't changed all that much, but it's no longer monochromatic. Does that make sense?"

Anton nodded. "Yes, it does."

"All right. If my view of the world was monochromatic, growing up in a Nouveau Paris slum under the Legislaturist regime, try to imagine just how little there is in the way of subtle shadings for a young man or woman who grew up here, as a seccy under the thumb of the Mesan regime."

Anton couldn't help but wince.

"Yeah," said Victor. " That's the problem, Anton. It's not that these kids are too fanatical. Frankly, I don't blame them one damn bit for their zeal and fervor. The problem is that they see everything in black and white. Forget the colors of the spectrum. They don't even recognize the color gray, much less any of its various shades."

A frown had been gathering on Yana's forehead, as she listened. "I don't get it, Victor. Why do you care in the first place? It's not as if you have any doubts any longer about their loyalties or dedication. Unless you've changed your mind over the last two days."

He shook his head. "It's not that I don't trust them. It's that I don't entirely trust their judgment. "

Anton leaned back in his chair at the kitchen table, and considered Victor's words. He understood what was concerning the Havenite agent. The group of young seccies—a fair number of them outright teenagers—with whom they'd established a relationship, using the liaisons provided by Saburo's contacts, had been very helpful. They provided Anton and Victor with a group of natives who knew the area extremely well, especially Neue Rostock. And they could also provide Anton and Victor with the assistance they might need in the future, depending on the way things developed.

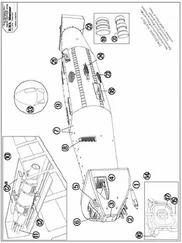

Furthermore, while they were young, and suffered from the haphazard education that all seccies received, they were very far from dull-witted or incapable. To Anton and Victor's surprise, for instance, when the group had been asked to provide them with a powerful explosive device, they'd proudly presented them a few days later with a low-yield nuclear device. Nothing jury-rigged, either. The device was a standard construction type used in terraforming, designed and built by a well-known Solarian company. The best Anton and Victor had expected had been something chemical and home-made.

So far, so good. But the same capability, when coupled to the narrow viewpoint Victor was describing . . .

He made a face. "You're worried they'll go off half-cocked."

Victor shrugged. "Not exactly. They're not fools, far from it. I'm mostly worried that, first, they'll slip on security. To really do counter-espionage properly you need to be patient and methodical more than anything else. That's . . . not their strength. So I think they're more open to being penetrated than they think they are. Secondly, I'm worried that if things do start to come apart, they're more likely to react by helping the process than trying to dodge it, if you know what I mean. Especially some of them—like David Pritchard. Who was just assigned the task of handling the device, if we need it."

Anton grimaced again. He hadn't attended the last meeting of the group. ("The group" was the only name they had. In that, at least, showing more of a sense for security that they did in other ways.) The decision to put Pritchard in charge of the device must have been made there.

There wasn't anything wrong with David Pritchard, exactly. But Victor and Anton both sensed that the youngster had a level of quiet yet corrosive fury that might lead him off a cliff, in the right circumstances.

But . . .

There really wasn't anything they do about it. It wasn't as if he and Victor had any real control of the group. Even its nominal leader, Carl Hansen, was no more than a first among equals.

"We'll just have to live with it. To be honest, Victor, I'm more worried at the moment about your situation with Inez Cloutier. Realistically, how much longer can you stall her?" He squinted a little. "You have, I trust, given up any idea of accepting employment?"

Victor sighed. "Yes, yes, yes. The voice of caution has prevailed. Although I hate to think what I'll be passing up."

For a moment, his expression had a trace of wistful sorrow. The sort of expression with which a normal and reasonable young man half-regrets his decision not to pursue a possible romantic involvement. On Victor Cachat's face, the expression signified his regret at not undertaking the harrowing risk of accepting employment with a rogue ex-StateSec military force, being dispatched to places unknown and with no way to get free that either he or Anton could figure out.

"You'd have to crazy to even think about it," said Yana. "And keep in mind that assessment is coming from a former Scrag."

Victor smiled. Then, ran fingers through his hair again. "We've got a bit of luck, there. Cloutier got called off-planet yesterday. At a guess, she's got to go consult with whoever is running this operation. I'm almost certain now that that's Adrian Luff, by the way."

Anton nodded. He and Victor had tentatively come to that conclusion a few days earlier, based on what Victor had been able to find out in the course of his negotiations with Cloutier.

Adrian Luff . . .

That was mostly bad news, according to Victor. Zilwicki really had no opinion of his own. He'd recognized the name from his days working for Manticoran naval intelligence, but that was about it.

Cachat knew more about him, as you'd expect, although he'd never actually met the man. According to Victor, Luff wasn't an especially brutal or harsh man, certainly not by StateSec standards. His advancement in State Security had been due primarily to his naval skills. He'd scarcely been what a professional Manticoran naval officer would have thought of as a peerless fleet commander, but at least he'd had a far better idea than most of his SS fellows about which end of the tube the missile came out of. And while no StateSec officer assigned to ride herd on the People's Navy was likely to be a total novice where brutality and discipline interdicted, Luff had understood that breaking a man's spirit wasn't the best way to produce a warrior when you needed one.

Читать дальше