Publius laughed, a thin mad sound. “Because — oh, this is a ripe irony — Tildoreamors belongs to me wholly, a Genched double, just like my Yubere.”

“I see,” said Ruiz. “Then we will go to your Yubere and release him and you will instruct him to do my bidding in every respect.”

As ruiz had hoped, the sampan was still moored to the quay. He moved a few of the crates, and made a place for Publius’s floater.

When he guided it aboard, the monster-maker reached out and patted at the produce with uncertain hands. “Vegetables? This is the best you could do, Ruiz?” His voice was still thin.

“Don’t complain,” said Ruiz, arranging the crates to hide the floater. “If I didn’t still need you to get out of SeaStack, I’d cut your throat and feed you to the margars.”

“Would you indeed? I don’t know… you’ve changed, gone soft, for all that you’ve bested Remint. You must have tricked him somehow….”

“How else?” said Ruiz sourly. “How badly are you hurt?”

“I’ll live, if you get me to a medunit. Would you moisten my eyes? They feel very strange.”

“No.”

“No?”

“No. And we’ll see about the medunit after you’ve fulfilled our bargain. Meanwhile, I like to see you suffer.”

Publius giggled. “No matter. And even if I die, I have my clones, who’ll surely get even for all this destruction. I confess, I’d prefer to keep this old brain; I’m comfortable in it. But times change and we must adapt, eh?”

Ruiz looked down at the blood-smeared face, the dull eyes, the still-arrogant mouth. “Don’t be so cocky, Publius. I drained your clones.”

A stricken look clouded the monster-maker’s face. He clamped his lips shut and said no more.

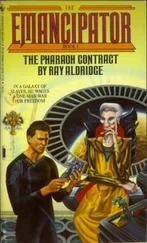

Nisa lived in grayness. Her cell was gray: the door, the walls, the floor, the narrow bench where she sat, the cot where she lay. The light that seeped from the ceiling was gray, neither bright nor dim, except for those times when it grew very faint and she slept. Even the food was gray and tasted of nothing.

She had grown listless in the days since the terrible Remint had thrust her into the cell and locked the door. She had lost track of time, or rather had abandoned it. On several occasions, she had awakened without a memory of falling asleep, and assumed that she had been drugged. She had no way of knowing how long those periods of unconsciousness had lasted, so she stopped caring. She drifted into an almost-comfortable apathy, which was easier than wondering if her mind had been altered in the awful manner Ruiz had described.

She rarely thought of Ruiz and his inexplicable treachery, preferring instead to dwell on happier times on Pharaoh, when she had been the favored daughter of the King. She remembered her father’s garden, and the pleasure she had taken with her many lovers, and the various delightful sensations of her patrician station: fine food, the best wines, silks and jewels, the worshipful attentions of her slaves.

After a while Pharaoh seemed more real than her present dull circumstances. It was only when she slept and dreamed that she was unable to maintain her carefully cultivated detachment. In her dreams, Ruiz Aw came to her and pleaded for forgiveness, and she pretended to accept his apologies. In dreaming, she concealed her hatred and led him on skillfully, so that she might make him vulnerable and wreak a dreadful vengeance on him. But the dreams were frustrating because she always woke before she could shatter his heart as he had shattered hers.

The worst thing of all was that she sometimes woke crying weak tears, sad that the dream was over, that he had slipped away again, even though she hated him and hoped never to see him again.

Occasionally she wondered if she were dead and in Hell. Perhaps all that had gone before had been a sort of purgatory. Had she failed that test and been condemned to this eternity of grayness? Ruiz Aw might well have been a demon of destruction, sent to beguile her. It seemed to her there was a good deal of evidence to support such a view.

To escape the dreams, she slept rarely and spent her artificial nights sitting in the darkness, remembering the blazing light of Pharaoh.

It was at such a time that the door groaned and slid back and Ruiz Aw stood there looking in at her.

The lights came up and her eyes watered, so that she could not see him clearly for a moment; he was only a shape against the brighter light of the corridor.

“Nisa?” he said, in a soft uncertain voice.

Her eyes grew used to the light, and she could make out his face. He was shockingly haggard, with thick stubble in the hollows of his cheeks and dark circles under his eyes. He looked much older. He wore the sort of rough garments a slave might wear, and the sleeve of his jerkin was crusted with dried blood.

In that instant of dismayed recognition her heart softened just a bit and she wanted to go to him.

But he held a long-barreled weapon in his hand, so he was not a prisoner. The situation seemed full of dangerous ambiguity. She couldn’t imagine where safety lay, here on this terrible world where evil seemed extravagantly magnified and treachery had been raised to a high art. Ruiz Aw had returned, but what did that mean? And was he to be trusted? She feared him almost as much as she loved him — and her heart was still sluggish with some cold burden.

She lifted her chin and did not speak.

When he saw her, Ruiz felt an almost-physical pain. She was white-faced and drawn. Her beautiful hair was a wild tangle, and she sat slumped over, as if ill. For a moment her eyes were dull and faraway, but then her head came up and her eyes filled with evaluation. She seemed damaged in some unknowable way — still lovely, but a stranger. His fault.

“Nisa,” he said again. “It’s all right. We’ll be leaving now.” He held out his free hand.

She stood slowly. She looked down at his hand, her expression shifting toward a painfully cautious hope. “Where will we be going?” she asked. “Am I allowed to ask?”

“Of course… we’re leaving SeaStack. We’ll find a launch ring downcoast, and get off Sook.”

Disbelief fell across her face like a dusty veil. “The others?”

“Them too, Molnekh and Dolmaero. We can’t leave them.”

She walked past him, her body taut with unhappy expectation, as though she expected him to hurl her back into the cell and laugh at her disappointment. He felt a terrible pressure in his chest, and his eyes watered. How could he explain? There was no time now; every minute they spent in Yubere’s stronghold increased the danger that Publius would find a way to thwart their escape.

When she came from her cell, Nisa saw an injured man on a slab of metal, floating unsupported in the corridor. His wounds were beginning to stink; he wouldn’t live long. Standing beside the man was another stranger, a small man with a closed face. The wounded man was whispering urgently to the other, who nodded.

“Who are they?” she asked.

At her question, Ruiz turned to look at Publius and the false Yubere… and saw that some murderous plot was being hatched.

A consuming rage filled him, blowtorch hot, fueled by all the awful things Publius had done to him and to others. He felt his vision grow dim with it, and it hammered in his head, demanding some release.

His finger spasmed on the trigger and Yubere’s head vaporized. The body fell across Publius and then slid to the floor.

“No,” said Publius feebly, wiping Yubere’s blood from his face. “Why did you do that? I was just asking him about your slaves… what had happened to them….”

Ruiz turned back to Nisa, who had become even more pale. “Always be vigilant around that man. He is the most wicked person you will ever meet; he is as devious as a snake and as cunning as a Dilvermoon herman. Presently he is blind and crippled and chained to the floater — and probably dying — but never forget that he is also the most dangerous person you will ever meet.”

Читать дальше