Some two miles from the camp, a mountain spur cut into the valley from the south while a recent massive landslide from the Rim pinched it to the north, leaving only a hundred feet clear between them. The cadets were racing for this bottleneck, the only place along the Betwixt where their inferior number might hold off the far larger Karnid horde.

But for how long? Jame wondered.

By now, hopefully, Brier had alerted Harn Grip-hard. The bulk of the Southern Host would come as soon as it could, but it would take time for a significant number to descend the Escarpment, and then how many horses had the cadets left them to reach this new battlefield?

Two miles for the cadets to cover, eight for the Karnids, but the former had spent a good half hour getting ready. Who would reach the gap first?

The mountain spur loomed ahead, its steep sides bristling with stunted trees and shrubs. Opposite it was a slope of rocky debris, reaching from the valley floor halfway up to a giant bite taken out of the Escarpment’s rim. Sunlight climbed both. Beyond, westward, the sky was still dark enough to show scattered stars, although building clouds soon obscured them.

Ah. The cadets were pulling up just short of the gap, with no Karnid yet in sight. They had won their race, for whatever good that might do them.

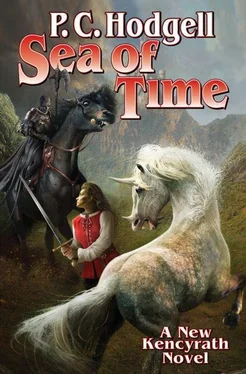

Jame hauled back on the reins, but the rathorn only tossed his head in irritation, almost unseating her, and plunged into the Kencyrs’ back ranks. Horses squealed, fighting to escape his rank scent. Some threw their riders and bolted back toward Kothifir. Others collided with their mates and fell in tangles of thrashing limbs.

“Sorry,” said Jame to startled faces as she bucketed past. “Sorry, sorry, sorry . . .”

She emerged through the broken front line to face a crescent of nine senior randon who had turned to observe her precipitous arrival.

“I don’t believe it,” said the Caineron, scowling. “Where did she spring from?”

None of them looked pleased to see her, Ran Spare least of all.

“You should turn back, Lordan,” he said. “This is no exercise.”

There was a jostling among the riders. Timmon emerged on her left riding a palomino, Gorbel to her right on a sturdy dark bay. The Ardeth wore hardened leather with rhi-sar inserts over gilded chain mail; the Caineron, a full suit of unornamented black rhi-sar. Most of the other cadets had donned less, down to mere padded jackets, depending on the wealth of their respective houses. Jame began to feel overdressed. She also felt rising anger.

“Why the Caineron and Ardeth Lordan, but not the Knorth?”

Death’s-head fidgeted under her. He wanted to get past these blockheads and at the enemy, whoever that might be. The officers’ horses stirred uneasily.

“For one thing,” said Ran Spare, “you see what effect that monster of yours has on our mounts. Are we to sacrifice the entire cavalry for one rider?”

He rode toward her as he spoke, calming his nervous mare with the touch of his hand. Death’s-head’s nostrils flared with interest. Pray Ancestors that she wasn’t in season.

“For another, have you ever fought in that armor? I thought not. For some reason, you’re also dripping wet. Worse, where is your helmet?”

Jame touched her bare face, shocked by memory. The helm with its fearsome guard of ivory teeth still lay on her bed in camp, where in her haste she had forgotten it. She hadn’t even missed it until now.

Fool, she thought. What am I doing here?

The randon was beside her now, their mounts head to tail. The rathorn sniffed. The mare stood her ground, although her withers darkened with nervous sweat. “Most important, though, there is this.” Spare spoke too softly now for anyone else to hear. “In the next hour, we may all die. Your lord brother survived Urakarn, otherwise no one would have known what happened to him or to the troops under his command. Someone must survive here too, to tell our story. Please, lady.”

Timmon rose in his stirrups and pointed. “Here they come!”

Beyond the gap, the valley widened and turned toward the southwest. Black-clad riders appeared around the bend, filling the Betwixt from side to side as their front line swung across it. They seemed to bring the wings of night with them, under whose shadow they rode in a many-legged mass. Likewise, their hoofbeats rolled together into a continuous rumble like distant thunder and dust rose like smoke in their wake. Through rents in the latter, one could see something looming behind them that was neither the Escarpment nor any Apollyne peak. Black it was, high and wide enough to dominate the sky, although its snowbound summit was broken. Columns of steam rose above it from its hidden interior and its flanks were fissured with cracks that glowed red in the dusk of its shadow.

“‘Black rock on the dry sea’s edge,’” Gorbel growled, quoting one of Ashe’s songs to the surprise of those close enough to hear. “‘How many your dungeons swallowed. How few came out again.’ D’you mean to tell me that that hulk is . . .”

“Urakarn,” breathed Timmon. “Or a counterfeit of it, like a mirage.”

Snow tumbled down from the heights and a cloud of ash belched up over its ramparts. Jame remembered the boiling lake and the seam of rising fire within the earth. Some moments later, the ground shuddered slightly underfoot, but any sound it might have made was swallowed by the rumble of the oncoming horde.

Jame watched the gray stallion in the vanguard. It really was Iron-jaw, she decided, who had been her father’s war-horse. She remembered Tori daring her to ride the brute, and that bone-jarring fall, and Tori dragging her back through the fence, out from under those deadly, steel-shod hooves. Iron-jaw had always had an evil temper. Then Ganth had ridden him to death in the Haunted Lands, searching for the Dream-weaver, his lost love. When the stallion had come back as a haunt, the changer Keral had claimed him for his master, Gerridon.

. . . we can always feed you to his new war-horse . . .

Was that who rode Iron-jaw now?

The figure on the haunt stallion’s back wore silver-gilt mail and black steel plate of an ornate, antique design that predated the Kencyrath’s experience on Rathillien with the rhi-sar. A horned helm obscured his features. It occurred to Jame that, despite growing up in his house, she had never seen the Master’s face clearly. He had always stood in the shadows, or behind her, or behind something else, such as those red, bridal ribbons. Tori had met him at least twice in his youth with the Southern Host but never face-to-face, if her experience of his dreams was to be believed. Only the Randir Matriarch Rawneth had had that dubious honor in the Moon Garden, but it was the changer Keral with whom she had mated, not Gerridon as she still believed.

How had she known one face from another?

How was Jame supposed to now?

“M’lord Caineron,” said Ran Spare, “take the rocky slope. We can’t afford to be outflanked. M’lord Ardeth, can you fortify that hill?”

It required someone who knew him to see the strain in Timmon’s answering smile, but it wasn’t cowardice. He hadn’t yet proved himself to his house. This might be his last chance.

“With pleasure,” he said, and wheeled his horse back into the crowd, followed by the Ardeth cadets.

Spare turned back to Jame. “Lady . . .”

Death’s-head snorted and pawed the ground. When he tossed his head, he nearly pulled Jame out of the saddle. Spare tried to grab his bridle, but Jame knocked his hand away before the rathorn could take off his arm.

It comes to this, she thought.

Ever since she had first seen the gray stallion and had guessed who might be riding him, this fight had become personal. The Master had betrayed the entire Kencyrath, but his own house first, including her own hapless father. And she owed him for a miserable childhood which she still only partly remembered.

Читать дальше