“Hello, Grandpa!”

Beyond the tower, out of focus, was the rim of the Escarpment.

“If you can see over that,” said Jame, “I’ll really be impressed.”

The image moved close to the rim, closer, and then the view angled sharply down toward the red tiled roofs of the camp.

“It’s all done with mirrors,” said the young man proudly.

Jame watched the flecks that were people swarming around the inner ward where local traders had set up the market that Rue had wanted to visit. A smaller cluster of specks was riding down the southern road, reminding Jame of the unfortunate Knorth ten-command whom that accursed note had sent forth to labor on this, their free day. She remembered the rest of her conversation with Rue, the things said, the things unsaid, and sudden unease gripped her.

“Can you show me the southern road?”

The retreating specks grew, then blurred, but not before she had counted them. There were only nine.

“Byrne, we have to go. Now.”

The boy set up a howl, but she found his arm in the dark and grabbed it. Where was the damned door? The image on the floor cast some reflected light over its surroundings even while its brilliance dazzled the eye. She tripped over a stool, breaking more glass, and lunged toward a faint, rectangular outline.

“Oh, I say!” protested the young man behind her.

“Sorry, sorry . . .”

Then they were outside, on the stair, down in the street. Byrne hung back, wailing with disappointment.

“Look.” Jame stopped short, still gripping his arm. “I apologize for dragging you away, but this is important . . . no, listen: sometimes grownups have to do things that children don’t understand. That’s part of what makes them grownups.”

Byrne wiped a snotty nose. “Like when Grandpa can’t play with me because he has to work?”

“Yes. Now, do you want to grow up or not?”

“Y-yes . . .”

“Then humor me.”

The child snuffled all the way back to the Armorers’ Tower, but stopped dragging his feet. Jame left him there with one of his grandfather’s journeymen.

“Get me down as fast as you can,” she told the liftmen at the rim, and stepped into the cage.

It fell out from under her. She clung to the bars, suspended above the floor, wondering if they had simply dropped it. The camp rushed up to meet her. Finally, her feet touched the floor, and then her knees almost buckled. The cage slammed down onto its platform, raising a billow of dust and causing yelps of alarm from its toll-keepers. Jame staggered out, into the camp.

“Lost your command, have you, Jamethiel?” Fash called out to her, laughing, as she ran past the Caineron barracks.

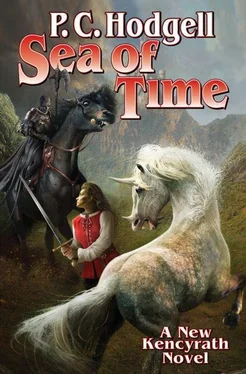

Her sixth sense told her that Bel-tairi was with the remount herd to the west of the camp while Death’s-head was ranging much farther afield. She called them both. Bel met her at the South Gate. She scrambled onto the mare’s bare back and they set off at a gallop down the south road towards the shadowy Apollynes.

IV

Brier and the rest of the ten-command had gotten perhaps ten miles away from Kothifir by the time that Jame caught up with them, having slowed Bel alternately to a trot and a walk so as not to overtire her. Jame rode up beside Brier Iron-thorn on her tall chestnut gelding. Bel’s head barely came up to his shoulder. Neither spoke for the next mile. The others tactfully fell back to give them privacy.

“You should have told me,” Jame said at last, nudging the Whinno-hir into a brief trot to catch up with the chestnut’s longer stride. Trinity, no wonder people used saddles; her tailbone throbbed with every bounce.

Brier shrugged. “You had other things to do. Besides, why should you waste a day with the rest of us?”

“Because I’m your ten-commander, idiot. I assume that precious note of yours included me.”

“It did. Specifically. In none too polite terms.”

“Which made you all the more determined to leave me out.”

Brier shrugged again. “It was a stupid order, and presumptuous, given who sent it, to demand that the Knorth Lordan do anything. To involve you in such nonsense demeans us all.”

Jame sighed. “If it had only been addressed to me, I might have torn it up the way Gorbel did with his challenge. Rue had it right: this little expedition proves nothing unless we run into a raid. But I am your commander and therefore responsible for you. In the future, we aren’t going to like many of the commands given to us, but we will still have to obey them. Do you have any spare water, by the way?”

Brier unhooked a goatskin pouch from her saddle and handed it down to her. Jame drank, then leaned forward to offer Bel a cupped handful of water. The mare’s pink tongue rasped her fingers dry, once, twice, and again.

“All right,” she said, straightening, a bit defensive. “I’m here without travel rations, tack, or even a weapon, discounting the knife in my boot. When I saw you heading out without me, well, I didn’t stop to think.”

She paused, flicked by her sixth sense. Death’s-head was nearby, but so was something else.

“Horses,” she said. “Strange ones.”

They were finally in the foothills of the Apollynes, their view restricted by rolling hills, shrubs, and giant rocks. Their mounts stirred uneasily as hoofbeats approached both ahead of them and behind. Could it be another Gemman raid like the one that had cost the young seeker her life?

The rathorn Death’s-head roared around a boulder lower down and surged up the incline toward them, his white mane roached up all down his spine and his tail flying like a battle standard.

Simultaneously, black mares erupted from the surrounding rocks with riders also in black, cheches concealing all but hard, bright eyes set in sun-dark faces.

“Karnids,” Brier snapped. “Circle up.”

The cadets backed rump to rump with Bel squeezed in the middle, in danger of being kicked by any one of them. Jame slipped off and dodged between the surrounding horses. Death’s-head swerved toward her, as usual nearly running her over but allowing her to grab his mane and swing onto his back as he surged past. The rathorn pivoted to face the mares, then paused, snorting. Some of them were in season. Their scent drew off his attention as others dashed in.

Jame found herself in the center of a swirling storm of horseflesh. Sleek black heads with red eyes snaked past. White fangs snapped at her. Hands grabbed. She drew her knife and hacked at them, all the time clinging to the rathorn’s mane, forced to ride high by the roached spine. Brier’s shout seemed distant. They were running away with her, the rathorn stumbling over rocky ground, striking almost at random.

Come. You know where you belong .

The image formed in her mind of a tall, black-robed figure lifting his arms to receive her. He wore a single, silver glove.

I hacked off that hand when it reached out between scarlet ribbons to claim me . . .

Death’s-head snorted and steadied.

Not my lady.

Then he stumbled again and threw Jame over his head. She fell among rocks and lay there, dazed. All around her iron hooves struck spark from stone. A hand grabbed her arm and jerked her up across a saddle, knocking the breath out of her. The dimming sky whirled overhead. Then it went black.

V

Flames leaped in the darkness, and black-clad figures hovered, flickering in and out of sight.

“Do you recant . . . do you profess . . . then we must convince you, for your own good.”

. . . gloves of red-hot wire . . .

Oh god, my hands! Burning, burning . . .

VI

Jame heard the fire crackle and cringed from the memory of searing pain. Ah, my hands . . .

Читать дальше