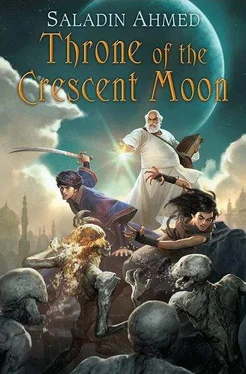

The old people went to prepare themselves, and Raseed found himself alone with Zamia. As soon as they were gone, she stepped close to him, and he fought furiously with himself to keep from breathing in her scent too deeply. When she spoke, he jumped, startled.

“Raseed bas Raseed,” she said quietly, “before we go to face our deaths, I would ask a question of you.”

“Yes?”

“Do you understand that, with my father dead, you must ask me directly if you wish for my hand in marriage?”

Raseed felt as if a sword had been slid into his guts. “I… I… Why would you ask…” he found he could not form words from his thoughts.

But the tribeswoman simply shrugged her slender shoulders. “The Heavenly Chapters tell us, O woman! Ask a hundred questions of your suitor and a hundred questions of yourself .”

“Suitor!?” Raseed had never before felt so lost within his own soul. Ten different men warred within him. “May God forgive me, Zamia Banu Laith Badawi, if I have behaved in a manner that… if I have shamed you by…”

“Shamed?” She looked baffled, which only confused him more. “How does shame come into this? I have simply seen the way you look at me. The only shame here would be born of deception. Can—?” she broke off at the sound of the Doctor’s heavy footsteps approaching from another room.

“If God grants us our lives beyond this day, we will speak of this again,” she said quickly. Then she nodded formally to him, ending the conversation.

Raseed went into his deep-breathing exercises, feeling more need for the calm they brought than he ever had. He stretched and prepared his mind and his body for battle, wondering whether he would die this day or live on with a soul full of shameful desires—and not knowing which would please God more.

The world was made of pain and the guardsman’s soul was formed from fear. How long had he sat unmoving in this cauldron, with only his head above the roiling red glow? He recalled, like dreams, slight sips of water and gruel. Some small, still-thinking part of him said that he was being kept alive while his body macerated slowly in the sparkling ruby oil.

The gaunt man in the filthy kaftan was there, holding open a sack of rich red silk. The shadow-jackal was beside him. The gaunt man upended the sack into the cauldron. Bones and skulls—men’s, but too small for men’s—spilled out with a ghastly clatter. Fragile looking skulls, tiny ribcages and fingerbones…

The shadow thing’s voice squealed again in his mind. Listen to Mouw Awa, who speaketh for his blessed friend. Thou art an honored guardsman. Begat and born in the Crescent Moon Palace. Thou art sworn in the name of God to defend it. All of those beneath ye shall serve.

Thou doth see the baby-bones. Infants fed and fed and then bled dry. All for the fear that doth now waft from thee.

Listen to Mouw Awa. His blessed friend hath waited so long for the Cobra Throne. Shortest days hath come and gone and gone and come. Never one quite right. Mouw Awa the manjackal knoweth well the pain of waiting. He helpeth to deliver his blessed friend from waiting, as his blessed friend did for Mouw Awa.

The gaunt man burned things before him. His eyes burned with smoke as the jackal-man droned on.

Thou smelleth the smoke of red mandrake and doth recall fear. Thou smelleth the smoke of black poppy and doth recall pain.

And suddenly, a whole piece of the guardsman’s mind slid back into place. He was Hami Samad, Vice Captain of the Guard, and there was nothing he could do but beg for his life through a cracked throat. “Please, sire! I will tell you whatever you wish! About the Khalif, about the palace!” He began to weep wildly. “Ministering Angels preserve me! God shelter me!”

The gaunt man stared at Hami Samad with black-ice eyes. The guardsman felt the gaunt man’s spindly fingers dig roughly into his scalp. The gaunt man’s eyes rolled backward, showing only whites. Horrible noises filled the room, as if a thousand men and animals were screaming at once.

There was a tearing noise, and there was pain a thousand times more searing than anything he had yet felt. Impossibly, he felt his head come away from his body. Impossibly, he heard himself speak.

“I AM THE FIRSTBORN ANGEL’S SEED, SOWN WITH GLORIOUS PAIN AND BLESSED FEAR. REAPED BY THE HAND OF HIS SERVANT ORSHADO. THE SKINS OF THOSE-WHO-WERE-BELOW-ME SHALL MOVE AT THE MUSIC OF MY WORD. ALL OF THOSE BENEATH SHALL SERVE.”

The last thing he saw was Hami Samad’s headless body in a great iron kettle, spurting blood that mixed with a molten red glow of boiling oil.

The sun was halfway up in the sky, and its heat was already making itself known. Dawoud sweated and huffed to keep up with the two young warriors and his indefatigable wife. He and Adoulla walked several strides behind the others, the ghul hunter’s breath coming nearly as heavily as Dawoud’s own. Ahead of them, Litaz spoke softly to Zamia and Raseed, but Dawoud and his old friend kept silent as they strode, saving their breath for breathing.

An hour passed, and the sun climbed a bit higher. They made their way through the large paved caravanserai that marked the entrance to the Palace Quarter. Ahead of them, a group of merchants argued heatedly with one of the Khalif’s coin collectors.

“Do you see this, brother-of-mine?” Adoulla asked quietly. “It’s not just the poor that the Falcon Prince speaks to. The Khalif has made his own bed of scorpions. He has even alienated the minor merchants with his taxes and his half-day-long tariff lines. The small timers are just waiting for an excuse to join the Prince’s supporters.”

Dawoud laughed. “That would be some alliance! Like a bad prophecy: ‘O watch for the day when the thief and the shopkeepers lie down together!’ ”

Adoulla gave him a sidelong glance. “It’s not so impossible. The Prince has always been daring. His targets have always been those with the biggest purses, men that most stall-keepers and middling merchants are happy to see get robbed.”

The road followed the new canal that had been diverted from the River of Tigers. Dawoud poked Adoulla and gestured to the tiny boats that moved along the canal, knowing that his friend had not yet seen this newly made marvel. The swift, magically moving water that the little boats bobbed on fed into a massive waterwheel. “Follow a twisty route of wafting spells and copper pipe, and this is the other end of the stink that now haunts our neighborhood every month. This thing can grind as much grain as ten normal mill wheels, you know.”

Adoulla snorted. “Yes, the end of the stick with no shit on it. Of course all the money from this monstrosity goes into the Khalif’s coffers. And now we’re off to save the son-of-a-whore’s dynasty.”

“Quiet!” Dawoud hissed as a watchman stepped out of a side alley, rudely crossing their path without so much as a glance at them.

The party stood and waited for the man to pass.

They approached the wheel. The noise it made—creaking wood, splashing water, groaning chains—was deafening. It was monstrous, Dawoud had to admit. One could scarce believe it was made by men.

Then they passed through a marble arch, and a path of smooth white paving-stones, wide enough for six riders, stretched ahead of them for a hundred yards. At the end of the great path, which was grander than the Mainway itself, lay the Crescent Moon Palace, behind a high wall. As always it forced Dawoud’s attention, though he’d been here just the other day.

Yet this time he found his eye drawn even more forcefully to the thin silvery spindle that was the minaret of the Court magi. So much space for seven men when seventy could live there . The Khalifs of Abassen had apparently never learned of the foul power that, for generations, had literally sat untapped beneath them. But what did the court Magi know? How would they fit into this mad sequence of magical events? He felt his tired mind spinning with too many damned-by-God complications.

Читать дальше