“But in the Name of Beneficent God,” the Doctor said to the teacake in his own voice, “I was made to devour you, little cakes, and my fate cannot be changed!” Litaz and Dawoud guffawed.

They are worse than children sometimes , Raseed thought. He was pleased to note that Zamia seemed unamused. She is serious about life, as a young woman should be. Chosen by God’s own Angels.

But then, as she continued to watch Adoulla’s bizarre little show, Raseed saw a smile creep across the tribeswoman’s full lips. Then a small, modest giggle.

Raseed found that he was not disappointed. He found, in fact, to his shame, that he could not look away from that smile. He found that Zamia’s little laugh cut through him like a sword poisoned with pure happiness. He tried to force his disciplined eyes to look away, but he could not. Zamia turned and looked directly at him. As her green-eyed gaze met his, and she saw him staring at her, a look of pure terror replaced the smile on her face.

She covered her mouth with her hand and bowed her head again. He followed suit, casting his eyes to the neatly swept stone floor. You were staring at her! You were staring at her, and you’ve shamed her. Have you no shame? Do you serve God or the Traitorous Angel?

He needed to be alone with his meditations—or as alone as he could be in this crowded house. He finished his bit of food and water, then begged to be excused.

“Go on, then,” the Doctor said. “I’ll be going to sleep soon myself.”

“Perhaps at this very table, big nose down in the teacakes, if precedent is any indication,” Dawoud said with a wicked smile.

The Doctor harrumphed, and the two old men started going at each other again. Raseed stood and headed down to find a quiet cellar corner.

“Don’t stay up all night praying and protecting, you hear me, boy?” the Doctor called after him. “You take a turn at watch, but get some sleep, too. On a hunt this dangerous, if you don’t stay alert you end up dead. Even you.”

Raseed made ablutions and meditated until he had pushed fear and the soft sound of Zamia’s laughter out of his thoughts. He’d thought he was too fired with duty to sleep, but sleep came.

The next thing he knew, Dawoud was waking him to take the last two hours of watch. As thin slivers of pink and orange light began to be visible through the window, he heard the strange magical pen-scratching sound of the cipher-spell at work, just as he’d heard it when going to sleep.

An hour later, as he sat on a stool by the front door, a loud voice suddenly boomed through the shop. Raseed leapt up in shock, his sword in his hand.

THE BROKEN WORDS ARE NOW MADE WHOLE! THEIR TRUTH FOR EVERY EYE AND SOUL!

It was the voice of Yaseer the spell-seller, coming from the workshop. Raseed cursed his own incompetence. How could the man have entered the house without Raseed seeing him?

But when he shot into the workshop, ready to kill if need be, there was no fat spell-seller there. The Doctor and Dawoud both followed him in, looking sleepy-eyed and unalarmed.

“Doctor, I heard an intruder’s voice!”

The Doctor looked at him sleepily, as if wondering who Raseed was.

“There’s no intruder, Raseed,” Litaz told him as she, too, entered the workshop, Zamia trailing behind her. The alkhemist wore her houserobe, but Zamia was already clad in her Badawi camel-calf suede. “That’s just Yaseer’s signature. A reminder, when the spell has done its work, of the man who crafted it.”

Raseed kept his eyes from meeting Zamia’s. He looked to the workshop table and saw that the scroll the Doctor had brought from Miri Almoussa’s was now glowing faintly. Beside it, atop a pile of what looked like burnt parchment, was the scroll case Litaz had been carrying.

Dawoud picked up the intact scroll and unfurled it, whistling an impressed whistle. “That Yaseer may be a sack of unprincipled scum, but he does good work, there is no denying. The scroll has been deciphered.”

“Now let us see if it’s got anything worth telling us,” the Doctor said.

They all settled into seats as Dawoud read aloud.

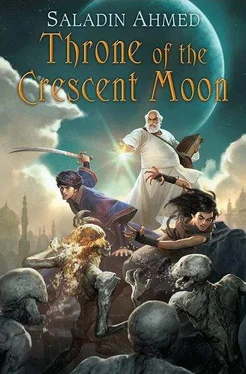

“No one knows how the Throne of the Crescent Moon was made. And few know that it was once called the Cobra Throne. Its great curved-moon back, which was once carved in the shape of the Cobra God’s spread hood, takes no mark or burn. The Kemeti Books of Brass, lost to us now, claimed that the Faroes, called also the Cobra Kings of Kem, sat upon it for their coronations, just as the Khalifs would come to do. But though the Khalifs have sat on it in coronation for centuries, there are those who say they know not its true power. That the throne was ensorcelled with unseen death-diagrams; bewitched by the Dead Gods, who loved treachery. That this power could be called only by spilling the blood of a ruler’s eldest heir upon it on the shortest day of the year. The Books of Brass claimed that he who managed to drink blood so spilled would be granted command of the most terrible death magics the world has ever known—master of the captive souls of untold numbers of long-dead slaves. The dark arts of the Cobra Kings, scoured from the world by God, would return.”

“It ends there.” The magus rolled the scroll and set it down.

The Doctor buried his face in his hands and let out a low groan. “Litaz, my dear, tell me, in the Name of Almighty God, who is Our Only Refuge, that you have some good, strong cardamom tea.”

A quarter hour later, they all sat planning in the greeting room, the elders drinking tea and smoking, the smell of apple tobacco wafting up from a water pipe.

“I do not want to do this,” the Doctor said. “We had a fine feast last night, and to open the morning with this dark talk…. But, I’ve been beaten and bruised, and my home lies burnt and ruined. I have lost my one true beloved and the promise of a peaceful life. I won’t lose my whole city as well. I won’t .”

He gestured with the pipe’s long mouthpiece at Dawoud. “But perhaps it won’t even come to that,” he said, sounding to Raseed as if he were trying to convince himself. “Do you think this Orshado is even capable of this? To break into the palace, let alone to wrest control of it from the watchmen and murder the Khalif’s son? Even to one such as I, who has seen his share of impossibilities, these seem near-impossible tasks. He would need allies within the palace, a dozen age-old incantations to get past its ward-spells—not to mention that there must be a thousand men guarding the Khalif.” The Doctor passed the pipe’s mouthpiece to Litaz.

Dawoud looked at the Doctor. “You don’t understand, brother-of-mine. You didn’t feel this ghul of ghuls. His cruelty. His power. How much these enable him to do when the Traitorous Angel works through him.”

“But even with war spells and death-diagrams,” Litaz broke in, exhaling smoke, “a throne is but a symbol. Without an army, without watchmen, his bloody design will only get him an angry mob storming the palace.”

“No,” the Doctor said, and Raseed saw the reluctant resolve rise in his eyes. “No, my dear, your husband is right. It’s not that simple. These are not dinar-grade magics we are dealing with here—no spells to rob houses or to make a murder look like an accident. These are the sorts of death spells the old books speak of—cruel magics through which every child, woman, and man in Dhamsawaat—aye, even the birds and the beasts—would wake one day to find themselves drowning on air, their lungs bursting like rotted fruit. The sorts of war spells that would allow one man to slay a horde, that would make an attacking army’s blood turn to boiling venom, that would turn a whole mob’s intestines into cobras. But it is even more than that. Such magics work as a… a focus. A man who knows how to use that magic could kill thousands in the space of a day. And then he would cull the foul power from those unwilling sacrifices to kill more men.”

Читать дальше