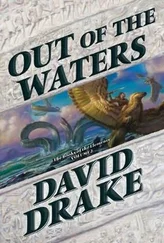

He paused, letting the shifting light and the pinnace’s motion confirm what he’d suspected. “Anyway, there’s a building on that headland,” he said. “It could be a temple, I think. A little one.”

“Wizard, where is this that we’ve fetched up?” Mounix snapped. “Hook, take the tiller, will you? Where’s the cities you told us about?”

“I don’t know,” said Metra, turning from her view of the shore to look back at the captain. “When we reach land, perhaps I’ll be able to learn more. Through my art.”

She spoke deliberately, using the words as a weapon to threaten and silence Mounix. Cashel was sure that the crew hadn’t known Metra was a wizard as well as a priestess when they’d signed on for the voyage.

“Cashel?” Tilphosa said quietly. “This morning, were you thinking about the sea serpent that wrecked us on that terrible island?”

He shrugged. “I thought about it,” he said, drawing his quarterstaff up from where he’d stored it along the boat’s side. “I’d never seen one before, though, and I don’t expect to see another one anytime soon.”

The staff’s iron butt caps already had a light coating of rust. Cashel drew out his wad of raw wool and began to polish first the metal, then the hickory itself.

“But what if it had been sent ?” the girl asked. “It could’ve still been waiting for us.”

“Well…” said Cashel as he continued his task. It relaxed him, even if he hadn’t needed to do it for the staff’s sake. “ I didn’t plan to spend the rest of my life in that place, mistress. I guess if the snake had showed up again, I’d have tried to do something about it.”

“Yes, I suppose you would have,” said Tilphosa. She giggled. For a moment Cashel thought she was getting hysterical. After reflection, he still wasn’t sure she wasn’t.

The tide was going out, though low water wouldn’t be till well into the first watch of the night. A narrow beach sloped gently to a limestone escarpment never more than two or three double paces high. There was vegetation on the rocks, ordinary woodland from what Cashel could tell in the dimming light. The one stone building was either a small temple or a tomb made to look like one.

“Well, it doesn’t seem like much,” Cashel said, “but we ought to get a night’s sleep. In the morning, we can go look for your Prince Thalemos or somebody who knows about him.”

The shore was rushing up at a surprising rate. Mounix called orders that meant more to the crew than they did to Cashel. With a rattle of brails, several men hauled the sail up to a quarter of its original area. They were going to chance grounding without unstepping the mast, though.

“We could’ve used some of this breeze at midday when it was so hot,” Cashel said, but it wasn’t a real complaint. No peasant expected the weather to do the thing that best suited him.

The shore was already in darkness, but arcs of white foam outlined the waves’ highest reach. Mounix had the tiller to starboard, bringing them in at a slant that would ease the impact.

“Get out quick when we ground,” Cashel said as he judged where the pinnace would touch. “The less weight in the bow, the better.”

He slid his quarterstaff back for Tilphosa to take. “And hold this for me,” he added. “Ah, if you would, I mean.”

It bothered Cashel when he wasn’t always polite when he was working on a problem. Things weren’t happening so fast at the moment that he couldn’t ask properly instead of just ordering the girl around.

“You men in the bow!” Mounix called. “Get ready to drag us up the beach when we ground!”

“I have the staff, Cashel,” Tilphosa said clearly. She gripped it in both hands, putting just enough pressure on the hickory to assure Cashel that he could safely release it.

“I’m ready!” Cashel said, though the other forward oarsmen didn’t bother to reply. Mounix waved a sour acknowledgment to him.

Metra sat on the pile of canvas over the storage jars amidships, her expression unreadable. Her eyes met Cashel’s; she was watching him and Tilphosa, not the land. Cashel nodded the way he’d have done with a chance-met neighbor he didn’t care for, then returned his attention to the shore.

The keel grated, then bumped momentarily harder as Cashel vaulted the port side. To his surprise Tilphosa was in the shoaling water just as quickly, but she’d judged his intent and leaped out to starboard so that she wouldn’t be in his way. She scampered through the foam and up the beach with the staff crosswise before her. It was more weight for a slight-built girl than Cashel had realized.

Cashel had his own job, though. The pinnace heeled toward him. He gripped the gunwale and his port oar at the rowlock, then strained forward.

The furled sail thumped down amidships, raising an angry shout from Metra. Cashel smiled faintly. The wizard hadn’t been quite under the sail and spar when Hook released them, but she was close enough to have been surprised. That was all right with Cashel.

Another wave curled up the sand. With the weight out of the far bow and the water lifting, the keel broke free from the trench it’d dug. Cashel strode forward, dragging the pinnace three short paces up before the wave sucked back. The sailors were tumbling out also; with their help the keel slid on several paces more before sticking where only the tide could lift it farther.

Two sailors staggered inland with the anchor, a section of ironwood trunk. The prongs of two branches had been cut to form flukes and a ball of lead was cast above the forks for weight. The men carried it to the edge of the escarpment and set it as firmly as they could. It wasn’t a safe tether—the sand wouldn’t hold the flukes—but it’d do till someone ran a line around the trunk of a tree above.

It was growing dark. Tilphosa’s face and the smooth, pale shaft of the quarterstaff were blurs against the weathered limestone. Cashel sloshed toward her, stepping over the anchor cable on his way.

He heard a sailor mutter something; he didn’t turn to make something of it. Most of Cashel’s life people had been calling him a dumb ox or some variation on the notion. Knocking people down wouldn’t make them think he was any smarter, so he didn’t bother.

“Cashel,” the girl said as she handed him his staff, “I don’t want to stay with the sailors tonight. Do we have to?”

Cashel ran his hands over the wood, checking it by reflex. “I don’t guess so,” he said. “I’ve got food in my wallet, enough for both of us. Biscuit, cheese, and a bottle of water is all, though. They’ll probably heat up a fish stew, you know. Well, salt fish.”

“I don’t care,” said the girl. “I heard the men carrying the anchor talking. They want to go back home, and they think if I’m with them, they’ll be safe from Metra.”

Some of the sailors were unloading the pinnace, but a good number of them had clustered around Mounix and Hook near the vessel’s prow. Their voices were lower than honest men would have needed to use, and their heads turned frequently in the direction of Cashel and the girl.

He couldn’t see their features. The sun was down, and the cliff threw a hard shadow over the beach.

“Let’s see what the temple’s like,” Cashel said. “It’s got a roof, anyhow.”

Storm-tossed waves had undercut the escarpment. Tilphosa was standing at a place where the limestone had collapsed into a slope of sorts—steep and irregular, but good enough even in the dim light. It wasn’t more than twice his height where they stood; well, maybe a little more.

Cashel expected to have to help the girl, but she turned immediately and started up using her hands as well as feet. She wasn’t as agile as Sharina would’ve been, but there wasn’t any doubt about her being willing.

Читать дальше