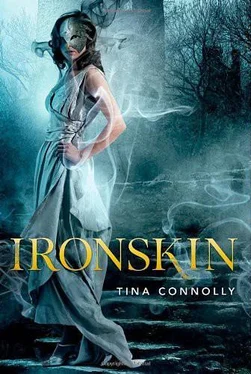

Ironskin

by Tina Connolly

Chapter 1

A House Cracked and Torn

The moor was grey, battlefield grey. It had been five years since the last fey was seen, but out here Jane could almost imagine the Great War still raged on. Grey mist drifted through the blackened trees, recalling the smoke from the crematory kilns. That was a constant smell in the last months of the war.

Jane smoothed her old pea coat, shook the nerves and fatigue from her gloved fingers. She’d been up since dawn, rattling through the frostbitten February morning on smoky iron train and lurching motorcar, until now she stood alone on the moor, looking up at an ink black manor house that disappeared into the grey sky.

The manor had been darkly beautiful once, full of odd minarets, fanciful gargoyles, and carved birds and beasts.

A chill ran down her spine as she studied the design of the house. You didn’t have to be an architecture student to recognize who had drawn up the plans for it. It was clear in the imprint of every tower and flying buttress, clear in the intricate blue glass windows, clear in the way the gargoyles seemed to ready their wings to swoop down on you.

The fey had designed this.

The frothy structures were still perfect on the south end of the building, on the carriage house. On the north the house had war damage. It had been bombed, and now only the skeleton remained, the scraggly black structure sharp and jagged, mocking its former grace and charm.

Just like me, Jane thought. Just like me.

The iron mask on her face was cold in the chill air. She wrapped her veil more tightly around her face, tucked the ends into the worn wool coat. Helen’s best, but her sister would have better soon enough. Jane leapfrogged the bits of metal and broken stone to reach the front door, her T-strap leather shoes slipping on bits of mud, the chunky heels skidding on wet moss. She reached straight up to knock, quick, quick, before she could change her mind—and stopped.

The doorknocker was not a pineapple or a brass hoop, but a woman’s face. Worse—a grotesque mockery of a woman, with pouched eyes, drooping nose, and gaping mouth. The knocker was her necklace, fitted close under her chin like a collar. An ugly symbol of welcome. Was this, too, part of the fey design?

Jane closed her eyes.

She had no more options. She’d worn out her welcome at her current teaching position—or, rather, her face had worn out her welcome for her. Her sister? Getting married and moving out. There had been more jobs for women, once, even women with her face. But then the war ended and the surviving men came slowly home. Wounded, weary men, grim and soul-scarred. One by one they convalesced and tried to reinsert themselves into a semblance of their former lives. One such would be teaching English at the Norwood Charity School for Girls instead of Jane.

Jane stuffed her hands into the coat’s patch pockets (smart with large tortoiseshell buttons; her sister certainly had taste), touched the clipping she knew by heart.

Governess needed, country house, delicate situation. Preference given to applicant with intimate knowledge of the child’s difficulties. Girl born during the Great War.

Delicate and difficulties had drawn Jane’s attention, but it was the phrase Girl born during the Great War that had let Jane piece the situation together. A couple letters later, she’d been sure she was right.

And that’s why she was here, wasn’t she? It wasn’t just because she had no other options.

It was because she could help this girl.

Jane glared at the hideous doorknocker, grabbed it, and banged it on the door. She’d made it this far, and she wasn’t going to be scared off by ornamental hardware.

The door opened on a very short, very old person standing there in a butler’s livery. The suit suggested a man, but the long grey braid and dainty chin—no, Jane was sure it was a woman. The butler’s face was seamed, her back, rounded. But for all that, she had the air of a scrappy bodyguard, and Jane wouldn’t have been surprised if that lump in her suit coat was a blackjack or iron pipe, hidden just out of sight.

The butler’s bright eyes flicked to Jane’s veil, glimmered with interested that Jane could not parse. She tapped her fingers on her bristly chin, grinned with sharp teeth. “An’ ye be human, enter,” the butler said formally, and so Jane crossed the iron threshold and entered the manor.

It was darker inside than out. The round foyer had six exits. The front door and the wide stairs opposite made up two. The other four were archways hung with heavy velvet curtains in dark colors: garnet and sapphire on the left, forest green and mahogany on the right. Worn tapestries hung on the stone walls between the curtains, dampening the thin blue of a fey-lit chandelier. Fey technology had mostly disappeared from the city as the lights and bluepacks winked out one by one and could not be replaced. It was back to candles and horses—though some who were both wealthy and brave were trying the new gaslights and steam-cars. Some who were merely brave were attempting to retrofit the bluepack motorcars with large devices that burned oil and let off a terrible smell—like the car that had brought her from the station. The housekeeper must have husbanded the chandelier lights carefully to make it last so long, when all fey trade had vanished.

“I’ll take your coat. That way for the artist,” said the little butler, and she gestured at the first doorway on the left, the garnet-red curtains.

“No, I’ve come for the governess position,” said Jane, but the butler was already retreating through the sapphire curtains with Jane’s coat and pasteboard suitcase, grey braid swinging. In that padded room her words died the second they fell from her lips.

Her steps made no noise as she walked over to draw back the curtain. It was not a hallway, but a small chamber, papered in the same deep garnet and lit with one flickering candle.

On the walls were rows of masks.

Jane stared. The masks were as grotesque as the doorknocker. Each was uniquely hideous, and yet there was a certain similarity in the way the glistening skin fell in bags and folds. Clearly they were all made by the same artist, but what sort of man would create these monstrosities—and who would buy them? They would fit a person, but surely no one would wear them, even for a whimsy like that masked cocktail party Helen had attended. In the flickering oil light they looked hyper-real, alive. Like something fey from the old days, before trade had given way to war. She lifted her veil to see more clearly, reached up to touch one sagging cheek.

“Do you like my collection?”

Jane jumped back, wrapping her veil close.

A man stood in the curtained entrance. The garnet folds swung around him as he stepped inside, stared down at her. He was very close and very tall in that narrow room, and his eyes were in shadow.

“Do people actually buy these?” she said, and was aghast at having blurted out something so rude.

But he didn’t look offended. “You’d be surprised,” he said, still studying her. He was not handsome, not as Helen would describe it—not soft and small-nosed, no ruddy cheeks and chin. He was all angles, the bones of his cheek and jaw plainly visible, and his hair leaped skyward as if it would not stay flat.

Jane tugged on the corner of the veil. She knew how much the gauze did and didn’t cover. The folds of the white veil obscured the details of her iron half-mask, but they didn’t hide that it existed. She caught them all looking, men, women, children. They stared into her veil, fascinated, appalled, trying not to get caught.

But he was staring into her eyes.

Читать дальше