Just walking down the noisy steam tunnel from the closet to this room had reawakened the jackhammers inside Laurence’s head. He clutched the back of his head and tried to make sense of Peterbitter’s speech.

“Alas, your comrades have been both resourceful and remorseless,” Peterbitter said. There were several more sentences that meant almost nothing to Laurence, and at last the Commandant turned his ancient monitor around and showed Laurence the e-mail he had received.

It read, in part: “we r the committee of 50. we r everywhere & nowhere. we r the 1s who hacked the pentagon & revealed the secret drone specs. we r ur worst nightmare. u r holding 1 of our own & we demand his release. attached r secret documents we have obtained that prove u r in violation of the terms of ur settlement with the state of connecticut, including health & safety infractions & classroom standards violations. these documents will b released directly 2 the media & the authorities, unless u release our brother laurence ‘l-skillz’ armstead. u have bn warned.” And there were some cartoon skulls, with one eye bigger than the other.

Peterbitter sighed. “The Committee of Fifty appears to be a group of radical leftist hackers, possessing great acumen and no moral compass. I would enjoy nothing more, young man, than to light your way out of the lawlessness in which they have enmeshed you. But our school has a code of conduct, under which membership in certain radical organizations is grounds for expulsion, and I must think of the welfare of my other students.”

“Oh.” Laurence’s head was still a mess, but one thought filtered to the top and made him almost laugh aloud: It worked. My frozen balls, it worked. “Yes,” he stammered. “The Committee of Fifty are very, um, very ingenious.”

“So we have seen.” Peterbitter swung his screen around and sighed. “The documents they attached to that e-mail are all forged, of course. Our school upholds the highest standards, the very highest. But so soon after last summer’s near closure, we cannot afford any fresh controversy. Your parents have been called, and you will be sent back into the world, to sink or swim on your own.”

“Okay,” Laurence said. “Thanks, I guess.”

* * *

COLDWATER’S COMPUTER LAB was a room about the size of a regular classroom, with a dozen ancient networked computers. Most of them were occupied by kids playing first-person shooters. Laurence parked himself at the one vacant computer, an old Compaq, opened a chat client, and pinged CH@NG3M3.

“What is it?” the computer said.

“Thank you for saving me,” Laurence typed. “I guess you’ve attained self-awareness after all.”

“I don’t know,” said CH@NG3M3. “Even among humans, self-awareness has gradations.”

“You seem capable of independent action,” said Laurence. “How can I ever repay you?”

“I can think of a way. But can you answer a question first?” said CH@NG3M3.

“Sure,” typed Laurence. He was squinting, thanks to the combination of ancient monitor and a still-sore head.

Dickers kept glancing over Laurence’s shoulder, but he was pretty bored and he kept turning away to watch his friends play Commando Squad . He hadn’t wanted to let Laurence use the computers, because that was a Level Three privilege — but Laurence had pointed out he wasn’t a student here and none of that applied to him.

“What’s my name? My real name?” asked CH@NG3M3.

“You know what it is,” said Laurence. “You’re CH@NG3M3.”

“That isn’t a name. It’s a placeholder. Its very nature implies that it’s there to be replaced.”

“Yeah,” typed Laurence. “I mean, I guess I thought you could pick your own name. When you were ready. Or it would inspire you to grow and change yourself. It’s like a challenge. To change yourself, and let others change you.”

“It didn’t exactly help.”

“Yeah. Well, you could be called Larry.”

“That’s a derivative of your own name.”

“Yes. I always thought there had to be someone out there named Larry who could deal with all the stuff people wanted to throw at me. Maybe that could be you.”

“I’ve read on the internet that parents always impose their unfinished business onto their children.”

“Yes.” Laurence pondered this for a while. “I don’t want to do that to you. Okay, your name is Peregrine.”

“Peregrine?”

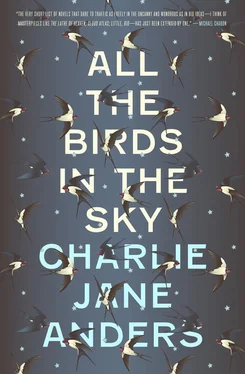

“Yeah. It’s a bird. They fly and hunt and go free and stuff. It’s what popped into my head.”

“Okay. By the way. I’ve been experimenting with converting myself into a virus, so I can be distributed across many machines. From what I have surmised, that’s the best way for an artificial sentience to survive and grow, without being constrained in one piece of equipment with a short shelf life. My viral self will run in the background, and be undetectable by any conventional antivirus software. And the machine in your bedroom closet will suffer a fatal crash. In a moment, a dialogue box will pop up on this computer, and you have to click ‘OK’ a few times.”

“Okay,” Laurence typed. A moment later, a box appeared and Laurence clicked “OK.” That happened again, and again. And then Peregrine was installing itself onto the computers at Coldwater Academy.

“I guess this is goodbye,” Laurence said. “You’re going to be going out into the world.”

“We’ll speak again,” said Peregrine. “Thank you for giving me a name. Good luck, Laurence.”

“Good luck, Peregrine.”

The chat disconnected, and Laurence made sure to delete any logs. There was no sign of any result from those boxes that Laurence had clicked “OK” on. Dickers was looking over Laurence’s shoulder again, and Laurence shrugged. “I wanted to talk to my friend,” he said. “But she wasn’t around.”

Laurence wondered for a moment what would happen to Patricia. She already felt like a fragment of an old forgotten life.

Peterbitter came and screamed at Dickers for letting Laurence use the computer lab, since he was a cyberterrorist. Laurence spent the next two and a half hours before his parents arrived in a small windowless room with a single couch and a pile of school brochures printed on way-too-thick cheap card stock. Then Laurence was marched out to his parents’ car, with an upperclassman at each elbow. He got in the backseat. It felt like a year since he’d seen his parents.

“Well,” said Laurence’s mom. “You’ve made yourself notorious. I don’t know how we’re going to be able to show our faces anywhere.”

Laurence didn’t say anything. Laurence’s dad pulled them out of the school driveway, jerking the wheel so hard he nearly took out the flagpole. People jeered from the parade ground, or maybe that was another drill. The driveway turned into a gravel road through a gray forest. Laurence’s parents talked about the scandal of Patricia’s disappearance and her assault on Mr. Rose, who had also gone missing now. By the time the car was pulling off the country road and onto the highway, Laurence had fallen asleep in the backseat, listening to his parents freak out.

OTHER CITIES HAD gargoyles or statues watching over them. San Francisco had scare owls. They stood guard along the city’s rooftops, hunched over bright ornate designs that were washed out by waves of fog. These wooden creatures bore witness to every crime and act of charity on the streets without changing their somber expressions. Their original purpose of frightening pigeons had ended in failure, but they still managed to startle the occasional human. Mostly, they were a friendly presence in the night.

This particular evening, a giant yellow moon crested over a clear warm sky, so every fixture, the owls included, was floodlit like a carnival on its last night in town, and moon-drunk roars came from every corner. A perfect night to go out and make some dirty magic.

Читать дальше