Alone, she wandered the village, and her camera was always at hand. She saw children playing in a small circular common area at the village centre, casting coloured stones into a complex grid marked in the dust with scattered chalk. A scoring system seemed to be in play, though she could not discern its details. The children laughed and giggled, but she heard nothing that resembled language. She watched for a while, hunkered down at the edge of the circle, snapping photos of the children at play. They knew she was there but didn’t seem concerned.

She walked through the rest of the village, and subconsciously perhaps she always suspected where she was going. When she reached the edge of the village, she had no doubt. The giant wall drew her, its size and splendour a gravity that lured her its way. As she approached and stepped into its shadow she looked around, careful to ensure no one saw her. The villagers seemed unconcerned when she left the village, and pushing her way through tall grasses and ferns, she saw no sign of any of them following her. There were paths here, trodden down over the years and mostly clear of vegetation. But she didn’t think they were well used.

The villagers seemed to be in control. Weaver knew that if they didn’t approve of what she was doing, where she was going, they would intervene. She took their silence as assent.

Close to the wall, its true scope and scale really hit home. She’d never seen the pyramids, but she had read and heard all about them. This structure might well be comparable, both in technical achievement and sheer size. Down close to the ground, some of the timbers and stone used in the construction looked incredibly old, with newer areas patched in, an ongoing maintenance effort that must continue for some of the Iwi villagers from birth to death.

When she walked closer and saw the hole, it was as if she’d always known it would be there. It was half hidden behind vines and a heavy dark-green ivy that mostly smothered this lower potion of the wall, and she only saw its dark depths when a flash from her camera illuminated the entrance. Splintered wood around the opening indicated that it had been made after the wall had been built, and some signs of a path revealed that the hole was in use. By humans or animals, she did not know.

Weaver moved closer, cautious and quiet. Birdsong continued around her. Crickets sawed away in the high grasses. Spiders scampered across fern leaves above her head, shadowy silhouettes running and pausing, running and pausing.

She pointed her camera directly at the hole, and the flash illuminated deep inside. It looked like a tunnel, and it was empty.

Weaver took a deep breath and looked around. If you’re watching, and if I really shouldn’t go this way, now’s the time to tell me , she thought. Her surroundings remained unchanged, and no Iwis materialised out of the undergrowth.

“If you’re not there, you can’t get the shot,” she said, and taking a small torch from her camera bag, she entered the hole in the wall.

It was cool inside, as if heat from outside could not find its way in. The tunnel was carved through the wall—heavy trunks hacked and splintered, rock chiselled and smashed away—and she could see tool marks in the walls and ceiling. The floor was made from trodden-down mud, hardened over time into a smooth, concrete-like surface. Painted hand marks were pressed to the stonework, and in places they formed complex patterns that made no sense to her.

She was not alone. Lizards scampered across walls and floor, skittering out of sight. Spiders ducked into crevasses. The torchlight swept her path, clearing these animals as effectively as a high-powered hose, and she did not hang around to see what else might be in there.

Daylight welcomed her from the other end, and after a minute walking beneath the great wall, she emerged onto the other side.

She was on a slight rise looking down onto a river valley, the river roaring from beneath the wall a hundred yards to her right. This was the part of the island that the Iwi protected themselves from. The dangerous part.

Though Weaver had already seen some of the danger, she felt suddenly exposed and watched by countless eyes she could not make out. She could see a lot more landscape on this side of the wall as the valley fell slowly away, and in the distance a range of mountains loomed like a giant beast’s staggered teeth. Maybe that’s what this is , she thought. The island’s one big monster just waiting to chew us up and spit us out .

She started taking photos. She couldn’t go far, yet curiosity got the better of her. She also had to be mindful of how many rolls of film she had left. It would have been easy to stand here and take fifty pictures of the landscape itself, trying to catch the wildness and wilderness, but she knew she was going to see more. The future was an uncertain place offering extraordinary experiences, and Weaver was determined to document it.

Something cried out. There was already a distinctive background sound to the island that she was growing used to—birds calling, insects scratching and whistling, frogs croaking, and the constant rustle and scamper of things unseen. This was louder, and obviously from something in pain.

She scurried down a slope, slipping in loose leaves and sliding the rest of the way, camera held in to her chest to prevent damage. At the slope’s base she stood and looked around, turning her head when the baying came again to try and discern direction.

Pushing her way through heavy, leathery leaves, boots sinking in soggy ground, she mounted a small hillock surrounded by swamp, and saw what was crying.

The chunk of helicopter fuselage was a shock set against the wild landscape, like a wound in this new reality. It was a large, ragged part of the tail section from one of the downed choppers, scorched along one edge where fire had eaten at it, the oil-blackened guts of the craft’s engine hanging out like a mechanical monster’s spilled insides. Trapped beneath it was a large water buffalo. It was crushed down into marsh by the weight on its back, one of its long horns chipped and scored from the metallic impact. The creature looked weak and almost ready to give in. Its struggles were slow, its cries wretched.

It saw Weaver and let out another feeble call.

Weaver lowered her camera and stepped down to the edge of the swamp. Water and mud played around her feet, and she knew if she went closer she’d be up to her knees at least. It was no choice at all. She waded in, feeling her boots sink into rotting vegetation beneath the water, swinging her arms and pushing hard as she approached the stricken creature.

Somehow, the buffalo knew that she was coming to help. It ceased its struggles and looked sidelong at her, its eye rolling in its skull with fear or hopelessness. Weaver muttered meaningless words to try and calm it, then started pushing at the fallen wreckage.

It did not shift. Not even a bit. She switched angles and heaved upwards against it from below, trying to shift her feet to gain more leverage, closing her eyes with the effort of pushing. It was stuck fast, too heavy to move—

—and then the whole piece of wreckage lifted up and away from her. She lost her footing and fell against the stricken buffalo, surprised by the sudden movement and crying out when the creature started to thrash and struggle.

The sun was gone. She noticed that at the same moment that she saw the huge leg beyond the buffalo.

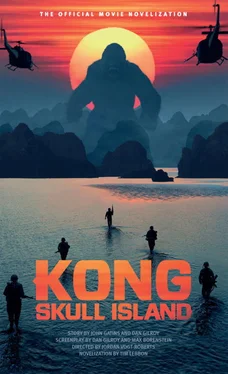

Kong was there. She took a few steps back and looked up, and up, and there he was, way above her, legs stuck down into the swamp like giant tree trunks, his huge body obscuring the sun, one arm held out as he flung the wreckage far into the swamp, the other arm hanging down. His fisted hand was the size of a car. She could feel the heat of him, smell his animal musk, and her skin prickled when her eyes met his.

Читать дальше