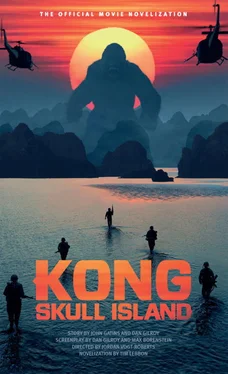

The ape scooped a huge handful of mud and water from the lagoon bank and began slathering an open wound on its forearm. Chapman froze in surprise, looking at his own arm, and the wound there that was troubling him. Something about that moment bit deep.

We did that to him , he thought, and for the first time since arriving he saw the beast as something other than a monster, and an enemy.

The ape paused, then looked directly at him. Its eyes changed. Its face wrinkled as it drew in a huge, snorting sniff. It reached out the mud-covered hand, crawling closer along the bank, reaching past Chapman’s rock—

—and then plunging its hand into the lagoon, right up to its elbow. Waves splashed and washed against the shore, and Chapman took the opportunity to push himself backwards, hugging the rock and desperately hoping it would shield him enough.

The beast withdrew its hand clasping a massive tentacled limb, suckers puckering at the open air. Water thrashed as more tentacles lashed out from the deep and wrapped around its arm, then the ape stood to its full height, pulling with all its strength.

A squid partially emerged from the water. This was a true giant, far larger than any Chapman had ever seen or even heard of before, perhaps eighty feet from tip of tentacles to the end of its tail. It was a powerful creature. Several limbs remained hooked onto something beneath the surface as the ape tugged and wrestled to haul it out. Water churned in the violent struggle, turning dark as the squid released sprays of thick black ink that spattered down around and over Chapman. It stank, a heavy viscous fluid that stuck to his clothes as thick as tar.

One of the squid’s tentacles lashed out across the rock Chapman was hiding behind. Even the tip was as thick as his arm, and it whipped him across the legs, a heavy wet impact. He cried out, voice lost amidst the fight between these two behemoths. Then he heard a sickening crunching sound, and risking a look around the rock he saw the ape chewing down on the squid’s head. Its skin ruptured, head burst, spilling a sick stew of rank fluids, sticking in the ape’s fur and forming a thick slick across the lagoon’s surface.

Chapman curled against the rock and waited for it to all go away. He was moaning softly, listening to the sounds of the giant ape eating. The tentacle end lying across his legs went limp, then was jerked away as the beast finished its meal.

He lay there for a while listening to the slurping, chewing sounds echoing across the lagoon. Squid blood and ink drifted across the surface like oil, and soon the scene became peaceful again, quiet, and when he chanced another glance around the rock the ape was gone, the squid was gone, and it was as if neither had ever been there.

“Shit,” Chapman muttered. “Shit.” He wanted nothing more than to get back to the crashed Sea Stallion.

Weaver was beginning to wonder whether she’d brought enough spare film cartridges. She was using thirty-six exposures, and already she’d filled six of them. She had maybe eight left to spare. Walking from the waterside and into the village, she saw sights she could have used eight rolls on barely without blinking.

The villagers, first of all. They all wore colourful clothing, much of it decorated with patterns and hues that were designed for camouflage against certain backgrounds. Some were jungle tinged, others pale as stone, yet more a muddy, dirty colour like jungle water. Men and women mixed together, seemingly equal. Whatever hierarchy existed here was not dictated by the sexes. Children ran around and played like children do, but even they wore smeared paint across their faces and naked torsos.

The village itself was fascinating. She’d seen similar stilted structures in Vietnam, built higher than potential flood levels, but these buildings were far more complex and sturdy. Their stilts were a mixture of timber and stone, and some of them covered three levels, often built into and around tall trees that might have been a thousand years old. They were also decorated with an array of highly coloured patterns, against which camouflaged villagers could stand and blend in. She wondered whether certain families chose particular colours and shapes.

She snapped photos, recording memories through the lens. The villagers did not react when she aimed the camera at them, neither posing, nor becoming agitated and turning away. They treated her camera like just another stranger. None of them seemed to react outwardly to anything, and she wondered just what they were thinking.

Beyond the village, further along the valley, was the wall.

It was the highest, largest structure they had seen by far, a massive conglomeration of stone and timber that effectively blocked off the valley past that point. It reminded Weaver of a tall dam, except that this appeared to be completely vertical. Huge stone blocks had been used to form the wall, along with timber infill structures in a couple of places that rose high and solid. Spiked areas—sharpened tree trunks, she guessed, set into stone pockets and protruding outward from the wall’s facade—gave the impression of a fortification.

Those same coloured streaks decorated the entire surface. They could not have been for camouflage, and she wondered if perhaps they had some ceremonial or superstitious meaning.

It was magnificent and daunting, and she had never seen its like before. She ached to get closer to make out more detail.

“Did they build that to keep out that thing we saw?” she asked.

“Kong,” Marlow said.

“It has a name?” Brooks asked.

“ He has a name. And yeah, to them he does. But he’s not the one they’re trying to keep out.”

Weaver’s blood ran cold. There’s worse than Kong , she thought, and it was not an idea she wanted to verbalise, or a question she wanted to ask. She and Conrad shared a glance and she saw her fear reflected in him.

“They’re petroglyphs,” Brooks said, pointing at some of the symbols used on buildings and the wall.

“No,” San said, “it looks more like a written language.” She started examining the symbols, as if to distract herself from everything that had happened. Weaver wished she had something to offer a distraction other than the view through her camera lens, and the words of this man who had been here forever.

“Did you teach them these building techniques?” Brooks asked.

“Me? Teach them?” Marlow laughed. “That’s rich. That’s a real riot.”

“Who’s in charge here?” Conrad asked.

“Nobody,” Marlow said. “They’re a democratic collective. Pretty neat, really. They don’t own property, there’s no crime. They’re past all that. Thing is, see, with a place like this, whatever lands here stays here.”

Several much older villagers approached, dressed in the usual coloured clothes but with jewellery of complex designs hanging around their neck and from heavily pierced ears.

“It’s okay,” Marlow said to the elders. “These are my friends. They mean no harm.”

The elders only stared at him and the new visitors, saying nothing and giving very little away through their expressions. Yet Marlow seemed to glean some meaning from their minimal movements and silence.

“Good, good, thank you,” he said. He turned to Conrad. “They say you’re welcome to shack up here.”

“I didn’t hear them say anything at all,” Conrad said, and Weaver shared his confusion and suspicion. This mad guy could be making everything up as he went along.

“They don’t speak much,” Marlow said, frowning as he tried to find words for what he meant to say. If he’d been here so long, perhaps his own language had lost some meaning. “It’s kinda nice, really. But once you’ve been here as long as I have, you get the message.”

Читать дальше