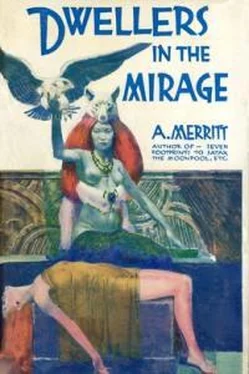

Абрахам Меррит - Dwellers in the Mirage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Абрахам Меррит - Dwellers in the Mirage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2017, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dwellers in the Mirage

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2017

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dwellers in the Mirage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dwellers in the Mirage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dwellers in the Mirage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dwellers in the Mirage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was good wine. I drank more than I should have. But clearer and clearer grew my plan for the taking of Sirk.

It was late next morning when I awoke. Lur was gone. I had slept as though drugged. I had the vaguest memory of what had occurred the night before, except that Lur and I had violently disagreed about something. I thought of Khalk'ru not at all. I asked Ouarda where Lur had gone. She said that word had been brought early that two women set apart for the next Sacrifice had managed to escape. Lur thought they were making their way to Sirk. She was hunting them with the wolves. I felt irritated that she had not roused me and taken me with her. I thought that I would like to see those white brutes of hers in action. They were like the great dogs we had used in Ayjirland to track similar fugitives.

I did not go into Karak. I spent the day at sword–play and wrestling, and swimming in the Lake of the Ghosts—after my headache had worn off.

Close toward nightfall Lur returned.

"Did you catch them?" I asked.

"No," she said. "They got to Sirk safely. We were just in time to see them half–across the drawbridge."

I thought she was rather indifferent about it, but gave the matter no further thought. And that night she was gay—and most tender toward me. Sometimes so tender that I seemed to detect another emotion in her kisses. It seemed to me that they were—regretful. And I gave that no thought then either.

Chapter XIX

The Taking of Sirk

Again I rode through the forest toward Sirk, with Lur at my left hand and Tibur beside her. At my back were my two captains, Dara and Naral. Close at our heels came Ouarda, with twelve slim, strong girls, fair skins stained strangely green and black, and naked except for a narrow belt around their waists. Behind these rode four score of the nobles with Tibur's friend Rascha at their head. And behind them marched silently a full thousand of Karak's finest fighting women.

It was night. It was essential to reach the edge of the forest before the last third of the stretch between midnight and dawn. The hoofs of the horses were muffled so that no sharp ears might hear their distant tread, and the soldiers marched in open formation, noiselessly. Five days had passed since I had first looked on the fortress.

They had been five days of secret, careful preparation. Only the Witch–woman and the Smith knew what I had in mind. Secret as we had been, the rumour had spread that we were preparing for a sortie against the Rrrllya. I was well content with that. Not until we had gathered to start did even Rascha, or so I believed, know that we were headed toward Sirk. This so no word might be carried there to put them on guard, for I knew well that those we menaced had many friends in Karak—might have them among the ranks that slipped along behind us. Surprise was the essence of my plan. Therefore the muffling of the horses' hoofs. Therefore the march by night. Therefore the silence as we passed through the forest. And therefore it was that when we heard the first howling of Lur's wolves the Witch–woman slipped from her horse and disappeared in the luminous green darkness.

We halted, awaiting her return. None spoke; the howls were stilled; she came from the trees and remounted. Like well–trained dogs the white wolves spread ahead of us, nosing over the ground we still must travel, ruthless scouts which no spy nor chance wanderer, whether from or to Sirk, could escape.

I had desired to strike sooner than this, had chafed at the delay, had been reluctant to lay bare my plan to Tibur. But Lur had pointed out that if the Smith were to be useful at Sirk's taking he would have to be trusted, and that he would be less dangerous if informed and eager than if uninformed and suspicious. Well, that was true. And Tibur was a first–class fighting man with strong friends.

So I had taken him into my confidence and told him what I had observed when first I had stood with Lur beside Sirk's boiling moat—the vigorously growing clumps of ferns which extended in an almost unbroken, irregular line high up and across the black cliff, from the forest on the hither side and over the geyser–spring, and over the parapets. It betrayed, I believed, a slipping or cracking of the rock which had formed a ledge. Along that ledge, steady–nerved, sure–footed climbers might creep, and make their way unseen into the fortress—and there do for us what I had in mind.

Tibur's eyes had sparkled, and he had laughed as I had not heard him laugh since my ordeal by Khalk'ru. He had made only one comment.

"The first link of your chain is the weakest, Dwayanu."

"True enough. But it is forged where Sirk's chain of defence is weakest."

"Nevertheless—I would not care to be the first to test that link."

For all my lack of trust, I had warmed to him for that touch of frankness.

"Thank the gods for your weight then, Anvil–smiter," I had said. "I cannot see those feet of yours competing for toe–holds with ferns. Otherwise I might have picked you."

I had looked down at the sketch I had drawn to make the matter clearer.

"We must strike quickly. How long before we can be in readiness, Lur?"

I had raised my eyes in time to see a swift glance pass between the two. Whatever suspicion I may have felt had been fleeting. Lur had answered, quickly.

"So far as the soldiers are concerned, we could start to–night. How long it will take to pick the climbers, I cannot tell. Then I must test them. All that will take time."

"How long, Lur? We must be swift."

"Three days—five days—I will be swift as may be. Beyond that I will not promise."

With that I had been forced to be content. And now, five nights later, we marched on Sirk. It was neither dark nor light in the forest; a strange dimness floated over us; the glimmer of the flowers was our torch. All the fragrances were of life. But it was death whose errand we were on.

The weapons of the soldiers were covered so that there could be no betraying glints; spear–heads darkened—no shining of metal upon any of us. On the tunics of the soldiers was the Wheel of Luka, so that friend would not be mistaken for foe once we were behind the walls of Sirk. Lur had wanted the Black Symbol of Khalk'ru.

I would not have it. We reached the spot where we had decided to leave the horses. And here in silence our force separated. Under leadership of Tibur and Rascha, the others crept through wood and fern–brake to the edge of the clearing opposite the drawbridge.

With the Witch–woman and myself went a scant dozen of the nobles, Ouarda with the naked girls, a hundred of the soldiers. Each of these had bow and quiver in well–protected cases on their backs. They carried the short battleaxe, long sword and dagger. They bore the long, wide rope ladder I had caused to be made, like those I had used long and long ago to meet problems similar to this of Sirk—but none with its peculiarly forbidding aspects. They carried another ladder, long and flexible and of wood. I was armed only with battleaxe and long sword, Lur and the nobles with the throwing hammers and swords.

We stole toward the torrent whose hissing became louder with each step.

Suddenly I halted, drew Lur to me.

"Witch–woman, can you truly talk to your wolves?"

"Truly, Dwayanu."

"I am thinking it would be no bad plan to draw eyes and ears from this end of the parapet. If some of your wolves would fight and howl and dance a bit there at the far bastion for the amusement of the guards, it might help us here."

She sent a low call, like the whimper of a she–wolf. Almost instantly the head of the great dog–wolf which had greeted her on our first ride lifted beside her. Its hackles bristled as it glared at me. But it made no sound. The Witch–woman dropped to her knees beside it, took its head in her arms, whispering. They seemed to whisper together. And then as suddenly as it had appeared, it was gone. Lur arose, in her eyes something of the green fire of the wolf's.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dwellers in the Mirage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dwellers in the Mirage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dwellers in the Mirage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)