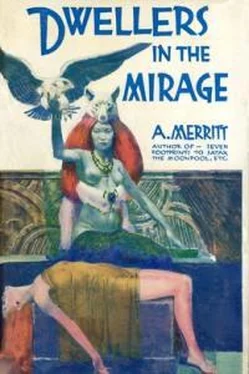

Абрахам Меррит - Dwellers in the Mirage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Абрахам Меррит - Dwellers in the Mirage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2017, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dwellers in the Mirage

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2017

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dwellers in the Mirage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dwellers in the Mirage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dwellers in the Mirage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dwellers in the Mirage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At right arose a bastion of perpendicular cliff, dripping with moisture, little of green upon it except small ferns clinging to precarious root–holds. At left, perhaps four arrow flights away, was a similar bastion, soaring into the haze. Between these bastions was a level platform of black rock. Its smooth and glistening foundations dropped into a moat as wide as two strong throws of a javelin. The platform curved outward, and from cliff to cliff it was lipped with one unbroken line of fortress.

Hai! But that was a moat! Out from under the right–hand cliff gushed a torrent. It hissed and bubbled as it shot forth, and the steam from it wavered over the cliff face like a great veil and fell upon us in a fine warm spray. It raced boiling along the rock base of the fortress, and jets of steam broke through it and immense bubbles rose and burst, scattering showers of scalding spray.

The fortress itself was not high. It was squat and solidly built, its front unbroken except for arrow slits close to the top. There was a parapet across the top. Upon it I could see the glint of spears and the heads of the guards. In only one part was there anything like towers. These were close to the centre where the boiling moat narrowed. Opposite them, on the farther bank, was a pier for a drawbridge. I could see the bridge, a narrow one, raised and protruding from between the two towers like a tongue.

Behind the fortress, the cliffs swept inward. They did not touch. Between them was a gap about a third as wide as the platform of the fortress. In front of us, on our side of the boiling stream, the sloping ground had been cleared both of trees and ferns. It gave no cover.

They had picked their spot well, these outlaws of Sirk. No besiegers could swim that moat with its hissing jets of live steam and bursting bubbles rising continually from the geysers at its bottom. No stones nor trees could dam it, making a causeway over which to march to batter at the fortress's walls. There was no taking of Sirk from this side. That was clear. Yet there must be more of Sirk than this.

Lur had been following my eyes, reading my thoughts.

"Sirk itself lies beyond those gates," she pointed to the gap between the cliffs. "It is a valley wherein is the city, the fields, the herds. And there is no way into it except through those gates."

I nodded, absently. I was studying the cliffs behind the fortress. I saw that these, unlike the bastions in whose embrace the platform lay, were not smooth. There had been falls of rock, and these rocks had formed rough terraces. If one could get to those terraces—unseen…

"Can we get closer to the cliff from which the torrent comes, Lur?"

She caught my wrist, her eyes bright.

"What do you see, Dwayanu?"

"I do not know as yet, Witch–woman. Perhaps nothing. Can we get closer to the torrent?"

"Come."

We slipped out of the ferns, skirted them, the dog–wolf walking stiff–legged in the lead, eyes and ears alert. The air grew hotter, vapour–filled, hard to breathe. The hissing became louder. We crept through the ferns, wet to the skins. Another step and I looked straight down upon the boiling torrent. I saw now that it did not come directly from the cliff. It shot up from beneath it, and its heat and its exhalations made me giddy. I tore a strip from my tunic and wrapped it around mouth and nose. I studied the cliff above it, foot by foot. Long I studied it and long—and then I turned.

"We can go back, Lur."

"What have you seen, Dwayanu?"

What I had seen might be the end of Sirk—but I did not tell her so. The thought was not yet fully born. It had never been my way to admit others into half–formed plans. It is too dangerous. The bud is more delicate than the flower and should be left to develop free from prying hands or treacherous or even well–meant meddling. Mature your plan and test it; then you can weigh with clear judgment any changes. Nor was I ever strong for counsel; too many pebbles thrown into the spring muddy it. That was one reason I was—Dwayanu. I said to Lur:

"I do not know. I have a thought. But I must weigh it."

She said, angrily:

"I am not stupid. I know war—as I know love. I could help you."—

I said, impatiently:

"Not yet. When I have made my plan I will tell it to you."

She did not speak again until we were within sight of the waiting women; then she turned to me. Her voice was low, and very sweet:

"Will you not tell me? Are we not equal, Dwayanu?"

"No," I answered, and left her to decide whether that was answer to the first question or both.

She mounted her horse, and we rode back through the forest.

I was thinking, thinking over what I had seen, and what it might mean, when I heard again the howling of the wolves. It was a steady, insistent howling. Summoning. The Witch–woman raised her head, listened, then spurred her horse forward. I shot my own after her. The white falcon fluttered, and beat up into the air, screeching.

We raced out of the forest and upon a flower–covered meadow. In the meadow stood a little man. The wolves surrounded him, weaving around and around one another in a witch–ring. The instant they caught sight of Lur, they ceased their cry—squatted on their haunches. Lur checked her horse and rode slowly toward them. I caught a glimpse of her face, and it was hard and fierce.

I looked at the little man. Little enough he was, hardly above one of my knees, yet perfectly formed. A little golden man with hair streaming down almost to his feet. One of the Rrrllya—I had studied the woven pictures of them on the tapestries, but this was the first living one I had seen—or was it? I had a vague idea that once I had been in closer contact with them than the tapestries.

The white falcon was circling round his head, darting down upon him, striking at him with claws and beak. The little man held an arm before his eyes, while the other was trying to beat the bird away. The Witch–woman sent a shrill call to the falcon. It flew to her, and the little man dropped his arms. His eyes fell upon me.

He cried out to me, held his arms out to me, like a child.

There was appeal in cry and gesture. Hope, too, and confidence. It was like a frightened child calling to one whom it knew and trusted. In his eyes I saw again the hope that I had watched die in the eyes of the Sacrifices. Well, I would not watch it die in the eyes of the little man!

I thrust my horse past Lur's, and lifted it over the barrier of the wolves. Leaning from the saddle, I caught the little man up in my arms. He clung to me, whispering in strange trilling sounds.

I looked back at Lur. She had halted her horse beyond the wolves.

She cried:

"Bring him to me!"

The little man clutched me tight, and broke into a rapid babble of the strange sounds. Quite evidently he had understood, and quite as evidently he was imploring me to do anything other than turn him over to the Witch–woman.

I laughed, and shook my head at her. I saw her eyes blaze with quick, uncontrollable fury. Let her rage! The little man should go safe! I put my heels to the horse and leaped the far ring of wolves. I saw not far away the gleam of the river, and turned my horse toward it.

The Witch–woman gave one wild, fierce cry. And then there was the whirr of wings around my head, and the buffeting of wings about my ears. I threw up a hand. I felt it strike the falcon, and I heard it shriek with rage and pain. The little man shrank closer to me.

A white body shot up and clung for a moment to the pommel of my saddle, green eyes glaring into mine, red mouth slavering. I took a quick glance back. The wolf pack was rushing down upon me, Lur at their heels. Again the wolf leaped. But by this time I had drawn my sword. I thrust it through the white wolf's throat. Another leaped, tearing a strip from my tunic. I held the little man high up in one arm and thrust again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dwellers in the Mirage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dwellers in the Mirage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dwellers in the Mirage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)