"What else?"

"I tire of Yodin. You and I—alone—could rule Karak, if—"

"That 'if’ is the heart of it. Witch–woman. What is it?"

She arose, leaned toward me.

"If you can summon Khalk'ru!"

"And if I cannot?"

She shrugged her white shoulders, dropped back into her chair. I laughed.

"In which case Tibur will not be so wearisome, and Yodin may be tolerated. Now listen to me, Lur. Was it your voice I heard urging me to enter Khalk'ru's temples? Did you see as I was seeing? You need not answer. I read you, Lur. You would be rid of Tibur. Well, perhaps I can kill him. You would be rid of Yodin. Well, no matter who I am, if I can summon the Greater–than–Gods, there is no need of Yodin. Tibur and Yodin gone, there would be only you and me. You think you could rule me. You could not, Lur."

She had listened quietly, and quietly now she answered.

"All that is true—"

She hesitated; her eyes glowed; a rosy flush swept over bosom and cheeks.

"Yet—there might be another reason why I took you—"

I did not ask her what that other reason might be; women had tried to snare me with that ruse before. Her gaze dropped from me, the cruelty on the red mouth stood out for an instant, naked.

"What did you promise Yodin, Witch–woman?"

She arose, held out her arms to me, her voice trembled—

"Are you less than man—that you can speak to me so! Have I not offered you power, to share with me? Am I not beautiful—am I not desirable?"

"Very beautiful, very desirable. But always I learned the traps my city concealed before I took it."

Her eyes shot blue fires at that. She took a swift step toward the door. I was swifter. I held her, caught the hand she raised to strike me.

"What did you promise the High–priest, Lur?"

I put the point of the dagger at her throat. Her eyes blazed at me, unafraid. Luka—turn your wheel so I need not slay this woman!

Her straining body relaxed; she laughed.

"Put away the dagger, I will tell you."

I released her, and walked back to my chair. She studied me from her place across the table; she said, half incredulously:

"You would have killed me!"

"Yes," I told her.

"I believe you. Whoever you may be. Yellow–hair—there is no man like you here."

"Whoever I may be—Witch?"

She stirred impatiently.

"No further need for pretence between us." There was anger in her voice. "I am done with lies—better for both if you be done with them too. Whoever you are—you are not Dwayanu. I say again that the withered leaf cannot turn green nor the dead return."

"If I am not he, then whence came those memories you watched with me not long ago? Did they pass from your mind to mine. Witch–woman—or from my mind to yours?"

She shook her head, and again I saw a furtive doubt cloud her eyes.

"I saw nothing. I meant you to see—something. You eluded me. Whatever it was you saw—I had no part in it. Nor could I bend you to my will. I saw nothing."

"I saw the ancient land, Lur."

She said, sullenly:

"I could go no farther than its portal."

"What was it you sent me into Ayjirland to find for Yodin, Witch–woman?"

"Khalk'ru," she answered evenly.

"And why?"

"Because then I would have known surely, beyond all doubt, whether you could summon him. That was what I promised Yodin to discover."

"And if I could summon him?"

"Then you were to be slain before you had opportunity."

"And if I could not?"

"Then you would be offered to him in the temple."

"By Zarda!" I swore. "Dwayanu's welcome is not like what he had of old when he went visiting—or, if you prefer it, the hospitality you offer a stranger is no thing to encourage travellers. Now do I see eye to eye with you in this matter of eliminating Tibur and the priest. But why should I not begin with you, Witch?"

She leaned back, smiling.

"First—because it would do you no good. Yellow–hair. Look."

She beckoned me to one of the windows. From it I could see the causeway and the smooth hill upon which we had emerged from the forest. There were soldiers all along the causeway and the top of the hill held a company of them. I felt that she was quite right—even I could not get through them unscathed. The old cold rage began to rise within me. She watched me, with mockery in her eyes.

"And second—" she said. "And second—well, hear me. Yellow–hair."

I poured wine, raised the goblet to her, and drank. She said:

"Life is pleasant in this land. Pleasant at least for those of us who rule it. I have no desire to change it—except in the matter of Tibur and Yodin. And another matter of which we can talk later. I know the world has altered since long and long ago our ancestors fled from Ayjirland. I know there is life outside this sheltered place to which Khalk'ru led those ancestors. Yodin and Tibur know it, and some few more. Others guess it. But none of us desires to leave this pleasant place—nor do we desire it invaded. Particularly have we no desire to have our people go from it. And this many would attempt if they knew there were green fields and woods and running water and a teeming world of men beyond us. For through the uncounted years they have been taught that in all the world there is no life save here. That Khalk'ru, angered by the Great Sacrilege when Ayjirland rose in revolt and destroyed his temples, then destroyed all life except here, and that only by Khalk'ru's sufferance does it here exist—and shall persist only so long as he is offered the ancient Sacrifice. You follow me, Yellow–hair?"

I nodded.

"The prophecy of Dwayanu is an ancient one. He was the greatest of the Ayjir kings. He lived a hundred years or more before the Ayjirs began to turn their faces from Khalk'ru, to resist the Sacrifice—and the desert in punishment began to waste the land. And as the unrest grew, and the great war which was to destroy the Ayjirs brewed, the prophecy was born. That he would return to restore the ancient glory. No new story. Yellow–hair. Others have had their Dwayanus—the Redeemer, the Liberator, the Loosener of Fate—or so I have read in those rolls our ancestors carried with them when they fled. I do not believe these stories; new Dwayanus may arise, but the old ones do not return. Yet the people know the prophecy, and the people will believe anything that promises them freedom from something they do not like. And it is from the people that the sacrifices to Khalk'ru are taken—and they do not like the Sacrifice. But because they fear what might come if there were no more sacrifices—they endure them.

"And now. Yellow–hair—we come to you. When first I saw you, heard you shouting that you were Dwayanu, I took council with Yodin and Tibur. I thought you then from Sirk. Soon I knew that could not be. There was another with you—"

"Another?" I asked, in genuine surprise.

She looked at me, suspiciously.

"You have no memory of him?"

"No. I remember seeing you. You had a white falcon. There were other women with you. I saw you from the river."

She leaned forward, gaze intent.

"You remember the Rrrllya—the Little People? A dark girl who calls herself Evalie?"

Little People—a dark girl—Evalie? Yes, I did remember something of them—but vaguely. They had been in those dreams I had forgotten, perhaps. No—they had been real…or had they?

"Faintly, I seem to remember something of them, Lur. Nothing clearly."

She stared at me, a curious exultation in her eyes.

"No matter," she said. "Do not try to think of them. You were not—awake. Later we will speak of them. They are enemies. No matter—follow me now. If you were from Sirk, posing as Dwayanu, you might be a rallying point for our discontented. Perhaps even the leader they needed. If you were from outside—you were still more dangerous, since you could prove us liars. Not only the people, but the soldiers might rally to you. And probably would. What was there for us to do but to kill you?"

Читать дальше

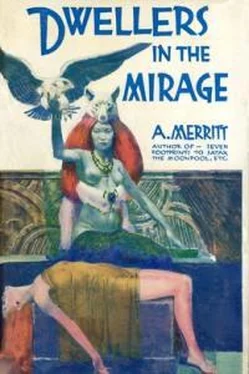

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)