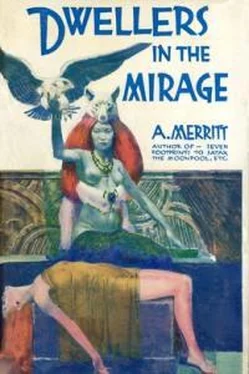

Абрахам Меррит - Dwellers in the Mirage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Абрахам Меррит - Dwellers in the Mirage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2017, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dwellers in the Mirage

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2017

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dwellers in the Mirage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dwellers in the Mirage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dwellers in the Mirage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dwellers in the Mirage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A gong sounded lightly. He pressed the side of the table, and the door opened. Three youths clothed in the smocks of the people entered and stood humbly waiting.

"They are your servants. They will take you to your place," Yodin said. He bent his head. I went out with the three young Ayjirs. At the door was a guard of a dozen women with a bold–eyed young captain. They saluted me smartly. We marched down the corridor and at length turned into another. I looked back.

I was just in time to see the Witch–woman slipping into the High Priest's chamber.

We came to another guarded door. It was thrown open and into it I was ushered, followed by the three youths.

"We are also your servants. Lord," the bold–eyed captain spoke. "If there is anything you wish, summon me by this. We shall be at the door."

She handed me a small gong of jade, saluted again and marched out.

The room had an odd aspect of familiarity. Then I realized it was much like that to which I had been taken in the oasis. There were the same oddly shaped stools, and chairs of metal, the same wide, low divan bed, the tapestried walls, the rugs upon the floor. Only here there were no signs of decay. True, some of the tapestries were time–faded, but exquisitely so; there were no rags or tatters in them. The others were beautifully woven but fresh as though just from the loom. The ancient hangings were threaded with the same scenes of the hunt and war as the haggard drapings of the oasis; the newer ones bore scenes of the land under the mirage. Nansur Bridge sprang unbroken over one, on another was a battle with the pygmies, on another a scene of the fantastically lovely forest—with the white wolves of Lur slinking through the trees. Something struck me as wrong. I looked and looked before I knew what it was. The arms of its olden master had been in the chamber of the oasis, his swords and spears, helmet and shield; in this one there was not a weapon. I remembered that I had carried the sword of Tibur's man into the chamber of the High Priest. I did not have it now.

A disquietude began to creep over me. I turned to the three young Ayjirs, and began to unbutton my shirt. They came forward silently, and started to strip me. And suddenly I felt a consuming thirst.

"Bring me water," I said to one of the youths. He paid not the slightest attention to me.

"Bring me water," I said again, thinking he had not heard. "I am thirsty."

He continued tranquilly taking off a boot. I touched him on the shoulder.

"Bring me water to drink," I said, emphatically.

He smiled up at me, opened his mouth and pointed. He had no tongue. He pointed to his ears. I understood that he was telling me he was both dumb and deaf. I pointed to his two comrades. He nodded.

My disquietude went up a point or two. Was this a general custom of the rulers of Karak; had this trio been especially adapted not only for silent service but unhearing service on special guests? Guests or— prisoners?

I tapped the gong with a finger. At once the door opened, and the young captain stood there, saluting.

"I am thirsty," I said. "Bring water."

For answer she crossed the room and pulled aside one of the hangings. Behind it was a wide, deep alcove.

Within the floor was a shallow pool through which clean water was flowing, and close beside it was a basin of porphyry from which sprang a jet like a tiny fountain, She took a goblet from a niche, filled it under the jet and handed it to me. It was cold and sparkling.

"Is there anything more, Lord?" she asked. I shook my head, and she marched out.

I went back to the ministrations of the three deaf–mutes. They took off the rest of my clothes and began to massage me, with some light, volatile oil. While they were doing it, my mind began to function rather actively. In the first place, the sore spot in my palm kept reminding me of that impression someone had been trying to get the ring off my thumb. In the second place, the harder I thought the more I was sure that before I awakened or had come out of my abstraction or drink or whatever it was, the white–faced priest had been talking, talking, talking to me, questioning me, probing into my dulled mind. And in the third place, I had lost almost entirely all the fine carelessness of consequences that had been so successful in putting me where I was—in fact, I was far too much Leif Langdon and too little Dwayanu. What had the priest been at with his talking, talking, questioning—and what had I said?

I jumped out of the hands of my masseurs, ran over to my trousers and dived into my belt. The ring was there right enough. I searched for my old pouch. It was gone. I rang the gong. The captain answered. I was mother–naked, but I hadn't the slightest sense of her being a woman.

"Hear me," I said. "Bring me wine. And bring with it a safe, strong case big enough to hold a ring. Bring with that a strong chain with which I can hang the case around my neck. Do you understand?"

"Done at once, Lord," she said. She was not long in returning. She set down the ewer she was carrying and reached into her blouse. She brought out a locket suspended from a metal chain. She snapped it open.

"Will this do, Lord?"

I turned from her, and put the ring of Khalk'ru into the locket. It held it admirably.

"Most excellently," I told her, "but I have nothing to give you in return."

She laughed.

"Reward enough to have beheld you, Lord," she said, not at all ambiguously, and marched away. I hung the locket round my neck. I poured a drink and then another. I went back to my masseurs and began to feel better. I drank while they were bathing me, and I drank while they were trimming my hair and shaving me. And the more I drank the more Dwayanu came up, coldly wrathful and resentful.

My dislike for Yodin grew. It did not lessen while the trio were dressing me. They put on me a silken under–vest. They covered it with a gorgeous tunic of yellow shot through with metallic threads of blue; they covered my long legs with the baggy trousers of the same stuff; they buckled around my waist a broad, gem–studded girdle, and they strapped upon my feet sandals of soft golden leather. They had shaved me, and now they brushed and dressed my hair which they had shorn to the nape of my neck.

By the time they were through with me, the wine was done. I was a little drunk, willing to be more so, and in no mood to be played with. I rang the gong for the captain. I wanted some more wine, and I wanted to know when, where and how I was going to eat. The door opened, but it was not the captain who came in.

It was the Witch–woman.

Chapter XV

The Lake of the Ghosts

Lur paused, red lips parted, regarding me. Plainly she was startled by the difference the Ayjir trappings and the ministrations of the mutes had made in the dripping, bedraggled figure that had scrambled out of the river not long before. Her eyes glowed, and a deeper rose stained her cheeks. She came. close.

"Dwayanu—you will go with me?"

I looked at her, and laughed.

"Why not, Lur—but also, why?"

She whispered:

"You are in danger—whether you are Dwayanu or whether you are not. I have persuaded Yodin to let you remain with me until you go to the temple. With me you shall be safe—until then."

"And why did you do this for me, Lur?"

She made no answer—only set one hand upon my shoulder and looked at me with blue eyes grown soft; and though common sense told me there were other reasons for her solicitude than any quick passion for me, still at that touch and look the blood raced through my veins, and it was hard to master my voice and speak.

"I will go with you, Lur."

She went to the door, opened it.

"Ouarda, the cloak and cap." She came back to me with a black cloak which she threw over my shoulders and fastened round my neck; she pulled down over my yellow hair a close–fitting cap shaped like the Phyrgian and she tucked my hair into it. Except for my height it made me like any other Ayjir in Karak.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dwellers in the Mirage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dwellers in the Mirage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dwellers in the Mirage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)