Despite the emergence of a nascent fan scene, and the staging of the country’s first SF/F convention in 1981, the bloom fell off the boom in 1982. That was when the June War with Lebanon helped sink an already strapped international convention in Jerusalem. Subsequently, the Israeli economy plunged into hyperinflation. (For example, the newsstand price of issue no. 33 of Fantasia 2000 (July 1982) was 37 shekels; issue no. 44 (August 1984) cost 750 shekels. In terms of purchasing power, these sums were roughly equivalent). In 1984, Fantasia ceased publication, having lost a major part of its readership.

The next attempt at a commercial SF/F magazine, Halomot beAspamia (Pipe-dreams in Spain, the place where castles are built, according to both Hebrew and English idiom), would begin publishing original Hebrew fiction in 2002 under the aegis of Nir Yaniv and Vered Tochterman. That effort, too, folded in 2008, to be revived in early 2016 as a web-based publication. An English-language fanzine, CyberCozen , published in English since 1988 by a fan club based in the town of Rehovoth, can be found online. [23] “About CyberCozen,” http://www.kulichki.com/antimiry/cybercozen .

Israel’s first SF-oriented website was created by Yaniv for the Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy in 1996.

The boom and bust cycle of Israeli SF/F faithfully reflected the vicissitudes of the Israeli economy (itself often subject to the vagaries of intermittent military crises). This view was taken by sociologist Nachman Ben-Yehuda, who attributed downswings to lingering ideological rejection by the wider culture of pluralism and its suspicion of individuated social subcultures. The cultural gatekeepers had lost much of their power, but they still held some of the keys to publication, controlling as they did the editorial boards of major publishing houses and various influential, if little read, literary magazines.

This went on until the mid-1990s, when the Internet hastened the ultimate fragmentation of the Israeli cultural matrix. As scholar Oren Soffer observes, its advent, and especially the penetration by cable and satellite television, resulted in a proliferation of global or, more specifically, American influences. These factors have been blamed by observers for a decrease in social cohesion and the reinforcement of (sub)group identity and individualism. These, Soffer says, “appear to be part of the social and cultural processes linked to the decline of national solidarity and, alternately, to the reinforcement of individual trends and consumer culture.” [24] Oren Soffer, Mass Communication in Israel: Nationalism, Globalization, and Segmentation (New York: Berghahn Books, 2015), 2.

Decentralization is still going on, helped by the diminished ability of the nation-state to supervise and control media messages.

Not surprisingly, Israel’s remaining cultural gatekeepers now found themselves with their backs against the wall. Although still intent on setting and patrolling the border between canonical and pop literature, they simply no longer had a single point of entry over which to stand guard. The walls themselves had become permeable, leading to a gradual yet unavoidable fragmentation of national identity. “Realism,” says Elana Gomel, is now “the Israeli fantasy.” [25] Gomel, “What Is Reality?” 36.

The social margins, as cultural commentator Stuart Hall argues, had paradoxically become highly charged and increasingly powerful places, especially insofar as the arts and social life are concerned. [26] Quoted in Soffer, Mass Communication , 14.

Not surprisingly, science fiction fandom, which combines the two, suddenly began to flourish in Israel.

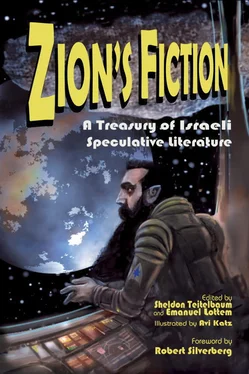

A more robust fan scene started emerging during the mid-1990s. In 1996, Hauptman, editor and translator Amos Geffen, and others joined the prolific translator (and Zion’s Fiction coeditor) Emanuel Lottem in founding the ISSF&F. Within the next few years several narrower special-interest groups took to the fore as well, including Starbase 972 (catering to the Israeli Star Trek fan contingent) and the Sunnydale Embassy ( Buffy the Vampire Slayer fandom). Both are now moribund. The Israeli Tolkien Community, the Israeli Society for Role-Playing Games, and AMAI, the Israeli Manga and Anime Society, all currently active (the last despite the oddly expressed displeasure of the Israel Defense Forces, which for a time refused to recruit its members), have shown greater staying power.

The ISSF&F, among its other achievements, has regularly staged several annual conventions, notably ICon, Olamot (Worlds), Me’orot (Lights), and Bidion (Fiction), some as collaborative events with one or more of the groups mentioned above. Its major thrust at international recognition within world fandom was to have been ArmageddonCon, intended to usher in the new millennium at Har Megiddo, known worldwide as Armageddon (on the correct date, namely midnight on December 31, 2000); alas, it had to be canceled because of the outbreak of the second armed Palestinian uprising, or Intifada.

Like other such organizations, the ISSF&F inaugurated a semiprozine, HaMemad haAsiri (The tenth dimension), which took over where Fantasia 2000 had left off in publishing original fiction by Israeli writers. It also features short original fiction on its website. In 1999 the ISSF&F inaugurated the annual Geffen Prize—named for its cofounder, revered translator and editor Amos Geffen (1937–98)—for the best original and translated SF/F material published in Hebrew during the previous year. Another award, the Einat Prize for hitherto unpublished short work in Hebrew, was launched in 2005 by the ISSF&F with the support of a private family-based foundation. Genre aficionado Ron Yaniv publishes the Geffen nominees and winners annually as e-books in a private venture. The Geffen Prize volumes began publication in 2002. In 2009 the ISSF&F replaced HaMemad haAsiri with the annual softcover volume Hayo Yihyeh (Once upon a future) to showcase new and unpublished short stories written for the most part in Hebrew. The scarcity of venues for short fiction in Israel in general affords these collections added import.

One area in which the ISSF&F utterly failed was its attempts (in which coeditor E. L. was involved) to persuade educators and Ministry of Education officials to include SF/F in school curricula. Some stories, they argued, possessed sufficient literary value to be included in literature classes’ reading lists. Others could be usefully included in science classes to bring some life into a regimen of eye-glazing textbooks. All these efforts were in vain: the remnants of the Old Guard had not yet perished, nor did they surrender. The gatekeepers still controlled what schoolchildren could read in classes.

On a more positive note, the organization of Israeli fandom proved crucial for budding writers who hitherto felt there was neither readership for their work nor colleagues with whom they could interact. Meeting like-minded individuals at conventions, and reading stories—and later on, novels—by aspiring writers just like themselves, there was no stopping them now. Some of their stories are included in this volume, and more, hopefully, will be showcased in subsequent ones.

More strikingly, several important mainstream writers, including three Prime Minister’s Prize recipients, decided to trade in their chips for a new stake in SF/F tropes and trappings. The late Nava Semel, for instance, published three SF novels (one of them under a pen name), an opera libretto, and a play; Gail Hareven, a masterful collection of short stories; and Shimon Adaf, a mammoth SF/F novel of great wonder and complexity, one that the unusually peripatetic and internationally acclaimed British-based SF/F writer Lavie Tidhar has described as the first Israeli genre masterpiece. Upon first anteing up, however, they discovered that one of the tables in the room had already been taken by such public luminaries as Shlomo Errel, a former naval commander-in-chief, and Amnon Rubinstein and Yossi Sarid, both past ministers of education. [27] Shlomo Errel, Undersea Diplomacy (Tel Aviv: Maariv Books–Hed Artzi Publishing, 2000); Amnon Rubinstein, The Sea above Us (Tel Aviv: Schocken Publishing House Ltd., 2007); Yossi Sarid, Accordingly We Are Here Assembled: An Alternate History [in Hebrew] (Tel Aviv: Yedioth Ahronoth Books and Chemed Books, 2008).

None of the latter would admit to having actually written science fiction. But their literarily established counterparts showed no such reticence. Their work, brazenly genre, proved exemplary.

Читать дальше