In A Man Lies Dreaming (2014), Israel’s immensely prolific and preternaturally peripatetic author Lavie Tidhar presents us with Hitler as a hack private eye after decamping to Great Britain following his failed 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. In The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism , Gavriel D. Rosenfeld says of his first encounter with a Hitler-victorious counterfactual, Robert Harris’s Fatherland (1992), that while the conceit startled him, the book itself was hardly a tour-de-force. At best, he attests, it was entertaining, a common descriptor of Len Deighton’s SS-GB and other such work. We may say much the same for former Israeli left-wing politician Yossi Sarid’s aforementioned novel Lefichach Nitkanasnu (“Accordingly, we are here assembled,” a memorable phrase from Israel’s Declaration of Independence), another bestseller in Israeli terms. [52] Lavie Tidhar, A Man Lies Dreaming (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2014); Robert Harris, Fatherland (Billings, MT: BCA, 1992), 372.

The book begins in 1948 and extends in year-long-segments well into 1967. What, Sarid asks, might have happened had the Zionist establishment extended a more complete and fitting welcome to Jewish refugees from Arab states who began to show up in 1950 after expulsion by their Arab neighbors? What, moreover, if they had been treated not as an unwelcome afterthought deserving of across-the-board underclass status, but of the same material assets and support afforded German and European Jewry? The what-ifs go on and on.

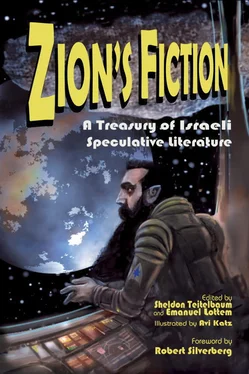

Themes and motifs aside, you will find in Zion’s Fiction a cornucopia of good to great stories. Generally speaking, these may be divided into two categories: stories written by mainstream and genre authors. Among the former you will encounter Gail Hareven’s superlative story “The Slows,” the only Israeli SF story ever published in The New Yorker (getting any SF/F story into The New Yorker is no mean feat, even in an issue dedicated to the genre). Others authors of the same ilk include Savyon Liebrecht, Nava Semel, and Shimon Adaf. But the majority of the stories were written by authors who grew up, in the literary sense, within SF/F, including Rotem Baruchin, Yael Furman, Guy Hasson, Keren Landsman, Eyal Teler, Lavie Tidhar, and Nir Yaniv, to mention but a few. Like so many genre authors worldwide, they were fans first, published writers later on. Their emergence and their impressive output are the reasons that made us offer this anthology to the wider readership they deserve.

One final point we wish to make concerns Russian-language SF/F writers now living in Israel. The Russian immigrants are reputed to supersede their native-born compatriots, no slouches themselves, in their consumption of books. And of all the kinds of books Russians love to read, SF/F ranks pretty highly. Highly enough that many of them view Israeli reticence over speculative fiction, indigenous or otherwise, as inexplicably nekulturny —“uncultured,” one of the worst insults in the Russian vocabulary.

For the moment, most of them still prefer to remain ensconced within a Russian-speaking milieu. Their SF/F fanzines, journals, and live-action role-playing clubs operate largely under the Israeli radar. The majority of Israelis have absolutely no intimation as to how this hidden literary geyser will soon erupt as their progeny swap Russian for Hebrew, and, should their parents’ literary predilections endure, change the nature of Hebrew belles lettres forever.

“I think the proportion of Russians to Israelis remain[s] roughly the same since the Great Aliyah of the 90s,” says the Ukraine-born Israeli scholar and writer Elana Gomel (whose story “Death in Jerusalem” we are delighted to present in this volume). “But I have no doubt that it has already significantly increased the appreciation of, and interest in, SF in Israel. The growth of festivals like ICon… the number of young Israelis who read/write SF (interestingly enough, often in English, even though it’s not their mother tongue), the emergence of Israeli comics, etc. In my classes on SF about half the students are ‘Russians’ (even though many of them grew up or were born in Israel).”

For them, we wait. And with them, we dream.

The Smell of Orange Groves

Lavie Tidhar

On the roof the solar panels were folded in on themselves, still asleep, yet uneasily stirring, as though they could sense the imminent coming of the sun. Boris stood on the edge of the roof. The roof was flat, and the building’s residents, his father’s neighbors, had, over the years, planted and expanded an assortment of plants, in pots of clay and aluminum and wood, across the roof, turning it into a high-rise tropical garden.

It was quiet up there and, for the moment, still cool. He loved the smell of late-blooming jasmine; it crept along the walls of the building, climbing tenaciously high, spreading out all over the old neighborhood that surrounded Central Station. He took a deep breath of night air and released it slowly, haltingly, watching the lights of the spaceport: it rose out of the sandy ground of Tel Aviv, the shape of an hourglass, and the slow-moving suborbital flights took off and landed like moving stars, tracing jeweled flight paths in the skies.

He loved the smell of this place, this city. The smell of the sea to the west, that wild scent of salt and open water, seaweed and tar, of suntan lotion and people. He loved to watch the solar surfers in the early morning, with spread transparent wings gliding on the winds above the Mediterranean. Loved the smell of cold conditioned air leaking out of windows, of basil when you rubbed it between your fingers; loved the smell of shawarma rising from street level with its heady mix of spices, turmeric and cumin dominating; loved the smell of vanished orange groves from far beyond the urban blocks of Tel Aviv or Jaffa.

Once it had all been orange groves. He stared out at the old neighborhood, the peeling paint, boxlike apartment blocks in old-style Soviet architecture crowded in with magnificent early-twentieth-century Bauhaus constructions, buildings made to look like ships, with long, curving, graceful balconies, small, round windows, flat roofs like decks, like the one he stood on—

Mixed amongst the old buildings were newer constructions, Martian-style co-op buildings with drop chutes for lifts and small rooms divided and subdivided inside, many without any windows—

Laundry hanging as it had for hundreds of years, off wash lines and windows, faded blouses and shorts blowing in the wind, gently. Balls of lights floated in the streets down below, dimming now, and Boris realized the night was receding, saw a blush of pink and red on the edge of the horizon and knew the sun was coming.

He had spent the night keeping vigil with his father, Vlad Chong, son of Weiwei Zhong (Zhong Weiwei in the Chinese manner of putting the family name first), and of Yulia Chong, née Rabinovich. In the tradition of the family, Boris, too, was given a Russian name. In another of the family’s traditions, he was also given a second, Jewish name. He smiled wryly, thinking about it. Boris Aaron Chong; the heritage and weight of three shared and ancient histories pressing down heavily on his slim, no longer young shoulders.

It had not been an easy night.

Once it had all been orange groves…. He took a deep breath, that smell of old asphalt and lingering combustion engine exhaust fumes gone now like the oranges, yet still, somehow, lingering, a memory-scent.

He’d tried to leave it behind. The family’s memory, what he sometimes, privately, called the Curse of the Family Chong, or Weiwei’s Folly.

Читать дальше