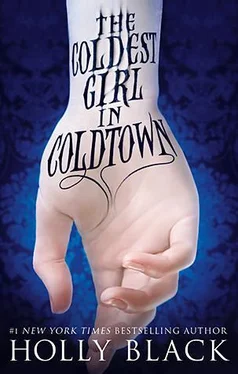

Now that she was out of his range, she set down the trophy carefully, back on the dresser, back where it belonged, back where it would be found by Lance’s parents and—Tana stopped herself, forced herself to focus on the impossible here and now. “What got you chained up?” she asked the vampire.

“I fell in with bad company,” he said, straight-faced, and for a moment she wasn’t sure if he was joking. It rattled her, the idea that he might have a sense of humor.

“Be careful,” Aidan called from the bed. “You don’t know what he might do.”

“We know what you’d do, though, don’t we?” the vampire accused Aidan in his silky voice.

Outside, the sun would be dipping down toward the tree line. She didn’t have much time to make good decisions.

She had to take her chances.

There was a comforter on the bed, underneath Aidan, and she started yanking on it. “I’m going for my car,” she told both of them. “I’m going to pull up to the window, and then you’ll both get in the trunk. I have a tire iron. Hopefully, I can snap the links with that.”

The vampire looked at her in bewilderment. Then he glanced toward the door and his expression grew sly. “If you free me, I could hold them off.”

Tana shook her head. Vampires were stronger than people, but not by so much that iron didn’t bind them. “I think we’re all better off with you chained up—just not here.”

“Are you sure?” Aidan asked. “Gavriel’s still a vampire.”

“He warned me about you and about them. He didn’t have to. I’m not going to repay that by—” She hesitated, then frowned. “What did you call him?”

“That’s his name.” Aidan sighed. “Gavriel. The other vampires, while they were tying me to the bed, they said his name.”

“Oh.” With a final tug she pulled the blanket free and tossed it over to Gavriel .

Her heart thundered in her chest, but along with the fear was the reckless thrill of adrenaline. She was going to save them.

There was a sudden scrabbling at the door, and the handle began to turn. She shrieked, climbing onto the bed and hopping over Aidan to get to the window. The garbage bag ripped free with one tug, letting in golden, late afternoon light.

Gavriel gasped in pain, pulling the blanket more tightly around him, turning his body as much behind another dresser as he could.

“Lots of sun still!” she shouted between breaths. “Better not come in.”

The movement outside the door stopped.

“You can’t leave me here,” Aidan said as Tana shoved at the old farmhouse window, swollen by years of rain. It was stuck.

Her muscles burned, but she pushed again. With a loud creak, the window slid up a little ways. Enough to get under, she hoped. The cool, sweet-smelling breeze brought the scent of honeysuckle and fresh-mowed grass.

Looking over at the lump of comforter and coats and shadow where Gavriel was hiding, she took a deep breath. “I won’t leave you,” she told Aidan. “I promise.”

No one else was going to get killed today, not if she could save them. Certainly not someone she’d once thought she loved, even if he was a jerk. Not some dead boy full of good advice. And she hoped not herself, either.

Leaning forward, she ducked her head under the window frame, ignoring the splinters of worn gray wood and old paint. She tossed out her purse. Then she tried to shimmy a little, to get the swell of her breasts over the sill and cant her hips so that she could grab hold of the siding and pull herself forward enough to drop down headfirst into the bushes. It was a short, bruising fall. For a long moment, the sunlight was too bright and the grass too green. She rolled onto her back and drank in the day.

She was safe. Clouds blew across the sky, soft and pulled as cotton candy. They shifted into the shapes of mountains, into walled cities, into open mouths with rows and rows of sharp teeth, into arms reaching down from the sky, into flames and—

A sudden gust made the branches of the trees shiver, raining down a few bright green leaves. A fly buzzed in the grass near her shoulder, making her think suddenly of the bodies inside, of the way flies would be landing on them, of the opalescent maggots that would hatch and tunnel, multiplying endlessly, spreading like an infection, until blackflies covered the room in a shifting carpet. Until all anyone could hear was the whirring of their glassy wings.

Tana started to shake like the trees, her limbs trembling, and was overcome by such a wave of nausea that she was barely able to twist onto her knees before she was sick in the grass.

You said that you were allowed to lose it , some part of her reminded herself.

Not yet, not yet , she told herself, although the very fact that she was renegotiating bargains with her own brain suggested things had already gotten pretty bad. Forcing herself up, Tana tried to remember where her car was parked. She walked across the sloping lawn, toward a line of cars and then past each, touching the hoods, feeling as if she was going to vomit again every time she noticed stuff inside—books, sweaters, beads hanging off rearview mirrors—the small tokens of people’s lives, the things they would never see again.

Finally, she got to her own Crown Vic, opened the door with a creak, and slid inside, drinking in the faint, familiar smell of gasoline and oil.

She’d bought it for a grand the day she turned seventeen and sprayed its scrapes with a can of lime green Rust-Oleum, making it look more like a vandalized cop car than anything else. She and her dad had rebuilt the engine together, during one of the few periods when he came out of his fog of misery long enough to remember he had two daughters.

It was big and solid, and it drank gas with an unquenchable thirst. When she slammed the door shut, for the first time since she walked out of the bathroom, maybe for the first time since she arrived at the party, she felt in control.

She wondered how long it would be before even that slipped through her fingers.

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4

Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure in life.

—Charles Frohman

Tana’s secret, the secret she never told anyone, was that she had a recurring dream. Sometimes months passed without her having it; sometimes she had it night after night for a week. In the dream, she and her mother were together, undead, dressed in billowy white gowns with ruffles at their collars and at the hems of their skirts. They ran through the night together in a darkling fairy tale of blood and forests and snow, of girls with raven’s wing hair and rose red lips and sharp teeth as white as milk.

The way they became infected was slightly different each time, but usually it went like this: Tana was the one who went Cold, not her mother. The details of that part were always elided, the hows and whos of the attack never asked or answered. The dream usually began with her father dragging her to the basement door and telling her he would never let her out again, never, ever, ever. Tana might howl and weep and plead in an orgy of grief, she might shower him with tears, but his heart was hard as stone. Eventually, he got tired of her weeping and pushed her down the stairs.

She hit her head against the wood slats and grabbed for the railing to break her fall. But although her nails scrabbled at it, she couldn’t catch hold. She wound up at the bottom with her breath knocked out of her.

There she sat, on the cold floor of the basement, as spiders crept over her hands and beetles clacked, as mice padded from shadows to squeak and steal strands of her hair for their nests, as she listened to her mother argue for her release and her sister cry. But every time her mother called her father cruel, he put another lock on the door, until there were thirty brass locks with thirty brass keys. Day after day, he had to open each lock to leave Tana a bowl of water and a bowl of porridge on the very top step. Then he had to lock her up all over again.

Читать дальше

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4