But still there was no peace for Danilov. The air trembled. Everything in the cave glowed and shook. Before Danilov's eyes stood the dazzling demon woman Anastasia, sparkling in her own right, and also because she was covered in precious stones. Of Smolensk blood, Anastasia was voluptuous and haughty, what you might call a cavalry maid: Sharing a fate similar to Danilov's, she was more successful than he. She laughed with delight, either present or future, and said in her beautiful mezzo-soprano: "So this is where you are, my darling Danilov! Why are you and your bracelet hiding from me?"

And without awaiting a reply from Danilov, she enfolded him in her powerful arms and held him tight. Trembling, Danilov wanted to push Anastasia away, but looking into her happy, faithful orange eyes, feeling her sweet hot body, he realized that he would not push her away, and it would have been stupid to do so. Let everything go to hell, he thought, and at that instant he forgot about everything else. And soon after in the Caribbean, despite all of Danilov's precautions, there arose a hurricane unpredicted by meteorologists. It impetuously blew over Florida and moved westward, tearing off iron roofs and rolling as gracefully as a truck over the cotton fields of Louisiana. The weather service gave it the watercolor name Pamela. Among Danilov's various, far-flung acquaintances there actually was a Pamela, but she had nothing to do with this hurricane.

5

There was a ring at the door. Actually, the Muravlyovs' bell was musical. It cost seven rubles, and its murmur was like the voice of a crane. Muravlyov, grumbling and hitching up his creased Polish jeans, went to open the door.

On the doorstep stood his wife, Tamara, carrying shopping bags as heavy as Alekseyev's weights.

"Well, come on in," Muravlyov said grumpily. "You must love those stores. You spend hours in them."

"What else can you do?" Tamara said with a sigh.

Muravlyov looked at the groceries. The beer was Zhiguli and with today's date, and there was kefir; his wife hadn't forgotten anything. But Muravlyov said, just in case: "You could have picked up more beer."

He followed his wife, and snatched a roll from the shopping bags she was dragging into the kitchen: "Danilov called."

"He calls every day," Tamara said, "but he never has the time to come over."

"He's coming today."

"Perfect!" Tamara was overjoyed. "I had this feeling. Green beans haven't been available in a long time, and I was at the grocery store and there they were. And I thought: If only Danilov came over for lobio."

"Well, he is coming," Muravlyov said, munching on the roll. "You start to cook, I have a lot of work."

After she caught her breath, Tamara peeked into the room of her son, Misha, who was given to brooding -- she hoped to see the fifth-grader struggling with his homework. But Misha was asleep, his head cradled in his arms on top of a piece of cardboard on the desk. Misha was quickly awakened, and Tamara saw that an article by the perceptive professor debunking the tales of aliens was mounted on the cardboard.

Around it was drawn knives, cannons, and fists, threatening the professor and the article.

"Oh, by the way, Vitya, how's Danilov doing with money?" Tamara remembered to ask.

Muravlyov, lying on the couch with a sports magazine, didn't reply right away.

"Money? The same ... even worse, I think."

"He said so?"

"He never says anything, you know Danilov..."

"What should we do?"

"I don't know," Muravlyov said. "I'll have that extra income ... and you wanted to decide about the fur coat..."

"Yes," Tamara said with a sigh. "I've got to decide about the fur."

The Muravlyovs owned a luxurious fur coat, a Siberian mink with black fate lines on the brown pelts. It was bought for six hundred hard-earned rubles from Tamara's coworker Inna Yakovlevna Olgina. The Muravlyovs were proud of it, and Viktor Mikhailovich Muravlyov himself was happy even on hot days to wear it on the balcony, to air out the coat and himself. However, the coat began cracking, as if it were made of tin, and exploding puffs on the flesh side. Furriers told them that it was hopeless and that they should have looked before buying -- it was a rotting coat. They suggested taking the coat without delay to a secondhand store to recoup at least some of their money. Their artist friend H. D. Eremchenko suggested turning the coat into mink brushes and selling them at a ruble apiece. There would be many buyers since the art supply stores had nothing but bristle brushes now. And in serving art, the Muravlyovs could get back not just their original six hundred rubles, but a cool thousand. But the Muravlyovs didn't want to part with the coat. They looked at it practically with tears in their eyes. They knew they might never have another coat like it again. However, now that Danilov's financial position was critical they had to make some decision.

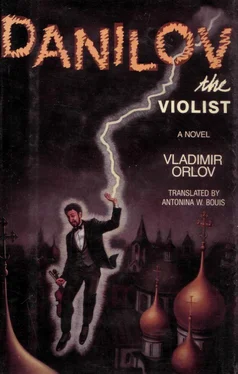

Danilov was paying off two co-op apartments and his viola. The instrument had cost him three thousand, borrowed from friends and friends of friends. He bought it four years ago.

It was made over two hundred years ago by the hands of Albani himself. Danilov had a studio apartment built for himself and gave the one-bedroom co-op with the good kitchen and black bathroom to his ex-wife, Klavdia Petrovna. He felt obligated to pay for both apartments. How could he not! Should a woman, a weak creature, be forced to pay for the necessities of living? Danilov was a musician, and music is pure spirituality. When his then-wife, Klavdia Petrovna, left Danilov, he ran after her, took her by the arm, brought her back to the apartment, and left himself. He was sick of his wife. He knew that he had made a mistake, that he didn't love her, and, for that matter, she didn't love him. They both felt better after the divorce. Klavdia Petrovna waged a deafening war with Danilov before the divorce. But when she learned that he was giving her the apartment and offering to pay for it, she immediately promised to be a true friend to him forever. And to this day she considered herself a friend of Danilov's -- to the extent that she invariably showed up every time he returned from performing abroad and went through his suitcases under the pretext of helping a tired man unpack. "What a wonderful thing this is!" she would exclaim and then add: "But what do you need it for, tell me, Danilov?" Danilov had meant a hundred times to tell this total stranger to leave him alone, but because he was shy he didn't and merely gave her the things she liked.

His new place in Ostankino resembled a coffin, but there was plenty of room for Danilov's instrument. He kept his old viola, too, worth three hundred rubles, the kind sold by the hundreds in stores. Danilov had wanted to sell it, but then decided that it might come in handy someday. The Albani viola had a magical sound. Full, gentle, sad, and kind, like the voice of a close friend. Danilov had hunted for that instrument for six years. He had had to beg for it from Gansovsky's widow, battle furiously, almost in hand-to-hand combat, with his rivals, spend sleepless nights. Finally he got it from her for three thousand. How he loved that marvelous viola even before it was his! How he bore it home! As if it were an infant, whose appearance no doctor, no fortune-teller could have foretold. And when he got it home and opened the old case, Danilov froze in adoration, ready to sink to his knees before it. But he didn't. He stood quietly before it. He was so shy he couldn't even touch it for two hours. He was almost certain that when he drew the bow over the strings, no sound would come, only silence and that would kill him, former musician Danilov. And yet he dared: Nervously, convulsively he touched bow to string, practically jerking them. The sound came, and then, conquering his fear and love, Danilov began handling the bow more calmly and skillfully, and something more than sound arose: melody. Danilov played a short piece by Darius Milhaud, then he put down the bow. He did not want to play any more that evening. He was afraid to scare away the instrument's first music. He was happy enough. "That's it," he told himself, "enough!" Now he felt like the true owner of Albani's viola. Not just the owner. The master! Those were magnificent moments. He could have danced with joy.

Читать дальше