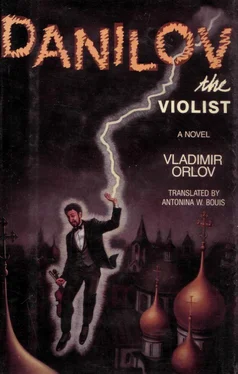

Danilov came out on the stage meaning to set the computer programmer straight: He wasn't a soloist but a member of the orchestra, and he certainly wasn't carrying a violin. However, something kept him from the first admission. He bowed to the audience and said courteously:

"Excuse me, but this is not a violin. It is a viola."

"A viola?" Leshchov was amazed. "If we had known that it is a viola, we would have adjusted the computer program..."

"It's all right," Danilov said soothingly.

As he sat down on the high-back chair upholstered in reddish vinyl and set his music on the stand, he kept thinking: "What if Natasha has left the auditorium and I never see her again?" But no, he sensed that she was here. Somewhere in the blackness of the auditorium she was looking at him, looking not out of idle curiosity but expecting music from him. Danilov lifted the bow. Now he could think of nothing but that he play the music properly, without betraying it or making any mistakes. He was attentive and precise, but his recent opinion that he could play these pieces easily, without a spiritual investment, now seemed overly self-confident and boastful. He made a mistake in the third piece, immediately lowered his bow, apologized to the audience, and started over. Suddenly everything started to go easily. Music was born. "Oh, my God," thought Danilov. "how good this is! If it could be like this always!"

When the sound died down, Danilov seemed unwilling to part with it: He held the bow on the strings for a long while, but finally lowered both bow and viola. The applause, the kind you might expect after Plisetskaya's leaps as Kitri, ruined his charmed state. In confusion Danilov looked at the audience, ready to plead: "What's the matter with you? Don't!

Don't... Sit quietly... Don't scare off my sounds, they're still here somewhere, they haven't flown away yet..." Danilov turned and saw that the people at the table were applauding heartily and that the guitarists, peering out from backstage, were giving him the thumbs-up sign.

Melekhin appeared at Danilov's side and whispered to him passionately. "You're a genius! You saved me! I didn't think you'd manage, after that third number I wanted to run away and hide somewhere... I swore at Misha Korenev, that shit, that traitor. But then you started! How you played! You turned your soul inside out for me! And that music was garbage, a piece of shit!"

"Shit," Danilov said with a nod, "shit..."

"Here, take this." Melekhin shoved an envelope at Danilov. "You'll see, we're not stingy..."

"What's this?"

"Money!"

"What money?" Danilov didn't understand. "What does money have to do with it?"

"Take it, take it," Melekhin said. "Stop fooling around."

In the meantime the programmer Leshchov was asking the audience which eight pieces in its opinion were written by the computer. The braver ones called out that it wrote the first three and nothing else. A young lab worker stood up and said that on the contrary, the computer had written all the pieces and played them, too, while the soloist merely moved the bow, in sync with the recording, the way they do on television. The audience hooted him down, calling him a fool, a computer nerd, and a pathetic jerk. They wanted him thrown out before the screening of Sun Valley Serenade. The scholars at the table tended toward the theory that the machine had written the early pieces. They asked Danilov what he thought. He said that he thought nothing. Then Leshchov said, with the solemn triumph of Turandot revealing the answers to the riddles that had doomed her suitors, the machine wrote pieces two, four, five, eight, and ten through thirteen. The audience sat in a shamefaced hush. But a discussion ensued.

Kudasov rushed into the fray, even though he had been invited for another part of the program. But Danilov did not listen. A few fragments of thoughts and sentences reached him, but they did not affect him. He sat there tired and emptied. His strength had left him. Danilov wanted coffee and cognac or even two mugs of beer. His mouth and throat were dry, as if the sounds of ten minutes ago had not been born in the viola but in Danilov himself, in his larynx and lungs. "How well I played!" Danilov returned to the thought. "Why was that?" And he worried that he might have accidentally switched his bracelet to the demon state.

But no, the links were in place. Danilov had performed in his human mode. "Good boy!" he said to himself. "So you can do it! If you played garbage like that, and for the violin to boot, then you really can play! Besides a little skill and a little talent, I must have had something else... Could I have been inspired?" He probably had, Danilov agreed with himself. Why shouldn't he? "I was playing for Natasha," Danilov thought.

"Now we will now ask the theater soloist," he heard Lesh-chov's voice, "to share his thoughts on the music written by the computer..."

"What does the computer have to do with it?" Danilov wanted to say. "Your computer is stupid. The music was in my soul!" Instead, he muttered uncertainly:

"Well... in general... Thanks to the computer ..."

"There!" Leshchov was pleased. "Even musicians are beginning to acknowledge the future. He is not the first to..."

"I wish they'd cut the chatter!" Danilov prayed, "so I could find Natasha..."

Sensing his impatience, Kudasov came up immediately and whispered: "Well? Are we off to the Muravlyovs'? Eh? Everything's getting cold..."

"They invited you?" Danilov asked harshly.

"Well ..." stammered Kudasov and shot Danilov a reproachful look, as though he had violated the rules of basic decency.

"So you go," Danilov said. "And give them my regrets. I can't... I haven't seen Sun Valley Serenade in such a long time ... and it's a musical."

"Well, I'll go," Kudasov said sadly. "But without you, they'll serve junk..."

Hurt, he clumsily moved away, his pockets stuffed with samples of the Wolves and Sheep chocolate candies.

Quietly, without waiting for the end of the discussion, which was obviously heading toward discrediting music by humans, Danilov and his chair edged toward the wings and off the stage. In the empty lobby he saw Natasha.

"It's you..." Danilov stammered. "Where's Ekaterina Ivanovna?"

"She's in the audience," Natasha said. "I was afraid that vou would leave now and I would never see you again. So I came out. Thank you for the music..."

"You liked it?"

"Very much! I haven't felt music that way in a long time..."

"You know," Danilov said with a shy smile, "for some reason, it worked for me today..."

After a silence, Natasha abruptly asked: "What about Misha Korenev? Why didn't he come? He was supposed to play those pieces, I heard..."

"Do you know Misha Korenev?" Danilov asked in amazement.

But the electric guitarists were finishing, moving the audience with words of purple passion; the doors opened into the lobby, and Natasha led Danilov into the auditorium, for the movie was about to start. The lights went out. Danilov sat between Ekaterina Ivanovna and Natasha. In his lap he held his beloved instrument like a sleeping infant. The film was good, as is any good reminiscence of childhood. But Danilov watched the screen absentmindedly, and even Glenn Miller's loud, happy tunes, innocent of the imminent death of the maestro in wartime skies, could not make Danilov forget that he was sitting next to Natasha. "What's happening to me?" thought Danilov. "Have I ever reacted to a woman like this before? It used to be fun. Carefree and exciting, just games. But now I'm trembling all over -- and it's been happening all evening! And ... Is this witchcraft? What if it's a setup?" But Danilov cast aside that vile thought. He was no longer tired and drained, the way he had been onstage. On the contrary, he felt his strength returning, and returning from the left side -- the side of his heart, where Natasha was right now.

Читать дальше