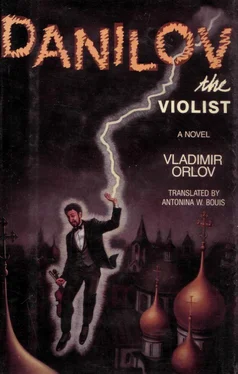

"Why did you do it, Nikolai Borisovich?" Danilov asked. "Were you incensed by my playing?"

"On the contrary," Zemsky said. "You played brilliantly. That's the whole point. But now you'll play even better."

"Then why -- "

"Volodya, call the police, I beg you, and file a complaint."

"I'm not calling anyone," Danilov said warily. "What can the police do now -- "

"I beg you... You don't have to call the police. I've already phoned. Just file a complaint."

"I'm not going to file any complaint..."

"I fall on my knees before you again, then."

"Why did you break it?"

"Don't you remember our conversation? You can believe or not in my works, my silencism, but I do. They can't be appreciated now. Not anytime soon. But who will remember me, who will suddenly take an interest in me a hundred or a hundred and fifty years from now? But now I'll be remembered! You will become a great musician. People will write articles about you, and somewhere someone will mention that some barbarian or jealous competitor destroyed your favorite instrument during the intermission of a concert. This is a good time for you! And for me! Some other future scholar will want to learn who that barbarian was, what had led him to destroy the Albani -- madness, or some higher principle. And someone will come to appreciate Nikolai Borisovich Zemsky for his works."

"Go away, Nikolai Borisovich, I want to be alone."

"No! First sign the complaint for the police!" Zemsky shouted with passion in his eyes.

"The police won't repair the viola," Danilov said.

"No one will be able to do that! I'll pay you for the instrument. You'll buy another one. How can anyone compare even an Albani with the direction that I am giving to music? ... You must demand to file a complaint. So that future archivists come across the document. And so that I do not remain nameless."

"Nikolai Borisovich, let's not talk about this anymore," Danilov said grimly.

Zemsky did fall on his knees before Danilov.

"Don't destroy me, Volodya! Do you want me to reveal the mystery of Misha Korenev to you?"

"Get up, Nikolai Borisovich." Danilov went over to him and tried to lift him, but Nikolai Borisovich was heavy. "Why are you driving me crazy witn this? It has nothing to do with me.

"There is a mystery concerning Korenev. But I can't say whether or not it has anything to do with you or with anyone else."

Nikolai Borisovich pulled a crumpled envelope from his jacket pocket and held it up.

"I got this letter from Korenev a day before his death," Zemsky said. "I didn't open it."

Zemsky handed it to Danilov. Danilov took it unwillingly but immediately offered it back.

"The letter is addressed to you. I don't read other people's mail."

"Open the envelope anyway. I have an idea of what's in it, and I don't think that your knowing the contents will damage either Korenev or myself."

Danilov carefully unglued the envelope and pulled out a sheet of music paper, obviously folded by nervous hands. He unfolded it. It was blank.

"Just as I thought," Zemsky said.

"A blank sheet," Danilov said softly. "Well, that's no great surprise to me, either..."

There was a knock on the dressing room door. "Come in," Danilov said.

Pereslegin asked tactfully: "Vladimir Alekseyevich, if you do not wish to play, just say so; no one will blame you."

Danilov said quietly, looking at the blank farewell sheet of music paper: "No, I'll definitely play now."

"Then your entrance is in twenty minutes."

As he spoke, two policemen came into the dressing room, one with a walkie-talkie. Danilov thought fearfully, "They'll start asking questions...." But the complaint was filled out, and it satisfied Nikolai Borisovich Zemsky.

From the hall came flute trills and string tremolos -- the nightingale had flown into the emperor's garden -- and then came the colorful and marvelous Chinese march. The two nightingales argued, the live one and the mechanical Japanese one. Danilov listened to the Stravinsky distractedly; he was thinking about the death of Misha Korenev. He saw the cemetery in Babushkino, the trampled snow under the birches, the weeping widow and two little girls, a grieving Natasha with roses in her hands. He saw himself. He was now holding the sum total of Misha's life: a blank piece of paper, a retreat into silence, an admission that there was nothing to say or that there was no need to say it. But there was a need, if he had jumped out of the window. He had said something that way, and something important.

The Nightingale ended with a harp glissando and the golden songs of the fisherman. It was Danilov's turn. He took a few minutes to accustom himself to Zakharov's viola; it had a nice sound. Danilov nodded to Pereslegin and Chudetsky and went out. The audience obviously knew about the incident with his Albani, and the silence was incredible.

Danilov announced: "An improvisation. In memory of a silenced musician."

As he announced it, he wondered if Zemsky would have named his composition that. But what difference did a tide make?

Danilov was in a state he himself could not identify: He felt love, and anger, and despair brought on by the destruction of his instrument; he wanted to tell people about the fate of the violinist Korenev and his opposition to it; he thirsted to express his concept of life, love, and music and to reconfirm them. He played. He felt freedom in the expression of his thoughts and feelings as never before. And that unfamiliar instrument became an extension of his voice, his mind, his heart... When Danilov realized that he had said everything he had to say today, he stopped.

There was applause, perhaps simply polite. Danilov stood and contemplated the unthinkable freedom with which he had played.

Had they understood him? Many said: "Unusual music... strange music ... as if we weren't listening to a viola at all. We have to hear some more." Even Pereslegin seemed a bit confused. "But you should go on speaking in your language," he counseled. "Unusual?" Danilov said challengingly. "They'll get used to it."

But he felt such courage only just after the concert. The next morning he awoke depressed. Music -- his own and others' -- revolted him. His so-called improvisation embarrassed him. "The hell with it all!"

That same morning he had an attack. He lay without moving, ready to call for an ambulance. It passed. There were no news reports about earthquakes. Only some news about breaking up student demonstrations in Thailand. So that's how it was. Of course, that's what they had promised Danilov. If you try to perfect yourself, try to be daring in your music; you'll heighten your newly acquired sensitivity. Sensitivity to elemental agitations and oscillations and to human agitations and oscillations. Soon he would break out in a rash from the cry of a hungry child in the Punjab. Or from the moans of a veteran with a piece of shrapnel digging into him. Or from the misfortunes of some artist, like Pereslegin, who was being sabotaged by the futecons. Or from anything else. "I'll put up with it," Danilov thought. "Some artist I'd be if I didn't."

And Danilov probably was right. After all, he was an artist, a musician. How could he exist without fantasy and imagination? And I, who listened to Danilov's tales and recorded several months of his life, consider the imagination to be one of the most wonderful aspects of human nature. So Danilov's fantasies and mine coincide. Naturally, there is no need to believe them. But why not? How far would humanity have gone if it didn't know how to fantasize? And how many edifying volumes would it have missed? The Bremen musicians would not have made mischief in the king's palaces. And Niels would not have flown on wild geese to freezing Lapland. And Major Kovalev's nose would not have had an opportunity to put on a uniform and undertake an attempt to reach Riga in a carriage... Danilov and I like to spin fantasies.

Читать дальше