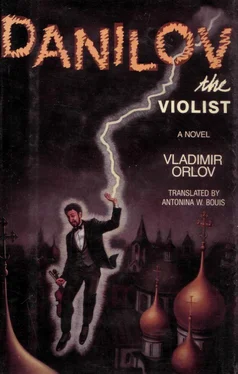

"I probably am more than just your lab assistant. I'm also the subject of your research, aren't I?"

Maliban was silent. Then he spoke in serious tones:

"Yes. But you should not see anything insulting in that. You are a gifted, creative character, and therefore of interest to us. I have a sense of who you are. You are not as simple as you like to think. Perhaps you are a new type, a response to the present state of the universe. Perhaps not. We are prepared for changes, for our and your pleasure. Why not consider your fate and your character edifying and worth studying? ... As for being a lab assistant, you did not understand me properly. A lab assistant is a flunky. We will not be sending you any tasks. I repeat: Live, and that's it. And don't show off among the futecons, don't invent any artificial twists of your own. Just react to situations that touch upon you, with all the sincerity of your real personality. Improvise, the way you do in your music."

Danilov tensed. Had he understood?

"No, I didn't understand your compositions," Maliban noted. "I simply listened to them... Incidentally, the hostility certain individuals have for you is precisely because of your daring in music. They feel you place yourself higher there than -- "

"Higher than what?"

"That was just an aside," Maliban said. "So forget it... If we need to, we'll call you. But that won't be for a long time... Oh, yes, I almost forgot. Pay attention to Rostovtsov."

"Rostovtsov?"

"No, he has nothing to do with us. But he's worth your attention."

"All right."

"That's all," Maliban said. "Go back to Ostankino."

He smiled for the first time during their talk. He was back in his black leather jacket and freshly laundered cotton shirt. "Forget about me. But don't forget the chandelier. I don't like reminding you about it. But what can you do? You really are frivolous. I'm not against frivolity; I can take you as you are. But I'm not the one who will be holding the chandelier over your head. Valentin Sergeyevich may not take our plans into account."

Maliban's eyes were cold and stern.

Later Danilov recalled Maliban's eyes more than once. "What can you expect from him," thought Danilov, "if his whole life is about doubt and experimentation?" Danilov considered experiments on living and rational, even relatively rational, creatures to be immoral, but Maliban found them delectable.

A multitude of acquaintances who had avoided Danilov now wanted to see him. Some even fawned over him. Danilov avoided such meetings and conversations. He saw Ugrael once, wearing his white Bedouin burnoose again. He looked disappointed and even seemed to bear Danilov a grudge. His lips traveled up to his ears, and he emitted sounds through his nostrils. "I'm off," Ugrael said, "back to the Arabian deserts!" He waved. "Oh, well," Danilov said. "At least it's warm there."

When Danilov finally was alone under the cuckoo clock, he smelled the delicate scent of anemones and sensed a signal. Danilov became excited as Himeko stepped out from behind the wardrobe. Slender, sad, in a green kimono, she stood before Danilov, her finger at her lips. Danilov nodded, promising to be quiet. Himeko dropped her hand. She smiled sadly at Danilov. Then she bowed, looked up with black, moist eyes, gazed at him for a long time, as if to drink him in, then nodded silently, and melted away.

Danilov wanted to rush after Himeko. But where? And for what? He sat down on the bed. He almost wept. Himeko had said good-bye to him. No one had forced her to do that, Danilov thought; she herself had decided that it was over. And she did not ask for his consent.

Even though Danilov consoled himself with the hope that Fate would bring them together again sometime, he was depressed. He would have mourned for a long time, had he not been called in to see Valentin Sergeyevich.

The conversation turned out to be unexpectedly brief. Valentin Sergeyevich praised Danilov's chess playing and reminded him how he had trembled at the meeting of house spirits on Argunovskaya Street when he saw Danilov's bishop. "But that wasn't you," Danilov said. "It was and it wasn't," replied Valentin Sergeyevich. This Valentin Sergeyevich said that he had not changed his opinion of Danilov, even though he had given it some thought. Then he added: "Do you wish to ask us about anything?" The expression in Valentin Ser-geyevich's eyes made Danilov think that this was the reason he had been called in. "No," Danilov said, "I have nothing to ask ..." "Well, then," Valentin Sergeyevich said with a nod, "it's up to you. Go." Danilov was excused.

In the Fourth Layer he saw Anastasiya.

"There you are!" Anastasiya said and took Danilov's hand.

The place was transformed. Danilov and Anastasiya were in a shady nook of a neglected garden, overgrown with reddish elders (which Danilov liked). Here and there in the elder thickets above the nettles and burdock grew faded jasmine. A white bench stood beneath the elders, and they sat down.

"Look at you!" Danilov said.

"How do I look?" Anastasiya asked delightedly.

"A real little cossack!"

Anastasiya wore a white silk blouse with flowing sleeves edged in gold braid. There was a sash around her waist, and her tight white velvet trousers were tucked into red boots.

"Why are you staring at me so shamelessly?"

Anastasiya was not flirting. Instead she was tender and meek. In the past she was accompanied by flashing lights, sonic booms, and geologic and maritime disturbances; every-thing had sizzled and moaned around Anastasiya -- she was passion itself. Now even the elder leaves did not rusde nor did overripe berries fall. Anastasiya was being modest. What was the matter?

"Don't be angry with me," Danilov said. "You know my situation."

"I'm not angry," Anastasiya said and glanced at him. "I have enough boyfriends. I'm satisfied with them. And I'm not in love with you."

Danilov did not know what to say to that. Then he remembered.

"Thank you."

"For what?"

"For healing me. For sewing up the hole with silk thread.

For everything. You were taking a risk then."

"A risk?" Anastasiya waved him off. "So what?"

She turned to him abruptly, pulled him closer, and said: "Danilov! Stay here! I beg you! What do you need Earth for?"

"What's the matter, Anastasiya? You yourself have Smolensk blood."

"No," Anastasiya said. "I'm a stranger on Earth. I'm better here. It's better here for all of us. Stay! I can do anything now. You'll be one of us here, with all your rights. I'll arrange it. Just stay. For my sake!"

There was entreaty and love in her eyes.

"I can't," Danilov said. "Forgive me."

"Then go!" she shouted. "Go! Right now! Good-bye! It's over! And don't look back!"

Danilov slunk away. He felt terrible. He did not turn around. Anastasiya might be weeping on the white bench. But had he turned around, he wouldn't have seen anything. Not the bench, not the elders, not Anastasiya.

Dear Anastasiya ... But what could he have said?

He had to go, as Valentin Sergeyevich ordered. Danilov went to the wardrobe, where his winter clothes were hung.

44

Danilov pulled the door toward him. It would not give. "I took the nails out," Danilov thought. He examined the door. The nails were in place. "How could that be?" He had to fuss with the nails.

The door opened and Danilov was under the arch of house 67. The clock on the corner of Bolnichney Alley showed twenty minutes after twelve. "So that's why the nails are in the door. I haven't taken them out yet."

To avoid any other problems, Danilov switched his bracelet to human state. People passed, people he had not seen before heading into the Nine Layers.

"Should I call Natasha from here or from Ostankino?" thought Danilov. He would have called right away, but he didn't have any coins in his pocket. Not a single one.

Читать дальше