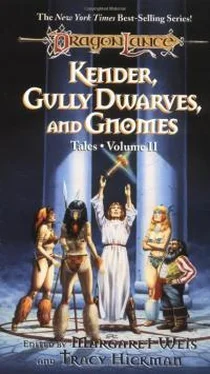

Ник О'Донохью - Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ник О'Донохью - Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1987, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1987

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Nonetheless, the chambers remained dangerous, and Armavir was instructed by the Mechanical Engineers Guild to remove these hazards. While dismantling one of the more complicated structures in an alcove of the main library at Mount Nevermind, Armavir stumbled across a surprising discovery—one that might well have brought about great technological advances had not the discoverer soon been distracted from his studies.

It seemed that one of the wires had been affixed between two ornamental copper helmets: one in the aforementioned alcove, the other in a similar chamber directly above. Sweating, entangled with wires, the young inventor began to detach the crucial strands and to his astonishment heard voices emanating from the helmet in the alcove. At first he imagined the accompanying ghost of the standard “speaking armor” legend [16] For related discussion of the “speaking armor” issue, see Philosophika Gnomikon MMXVII (323 A.C.), pp. 675,328—682,465.

, but decided otherwise when he heard only giggling and the rustle of clothing that had been, like the helmet in question, long abandoned.

It seemed that wire could conduct sound as well as heat, and the thoughts of young Armavir were immediately patriotic: an elaborate early warning system of wires stretched taut from the undercity to the world aboveground, where they could be affixed to metallic bowls cleverly disguised as fruit or stars, and positioned in the huge vallenwood trees on the slopes of Mount Nevermind.

Then below, in a place of safety, those in charge of the city’s defense could hear any threatening movement by those who dwelt beneath the sun and the moons, and could act accordingly, preventing surprise and possible ambush [17] Such an idea is scarcely more fanciful than others proposed by advocates of strong military defense. See, for instance, Theros Ironfeld, “Arms for Hostages,” War of the Lance Veteran IV , pp. 42-57.

.

Excited by his developing project (which he lovingly entitled “Star Wires”), Armavir decided to put his findings to the test before submitting them to the Mechanical Engineers Guild. Making his way to the upper world bearing a helmet, 100 feet of wire, an augur, and a detailed map of the undercity, he began by drilling into the earth beneath several of the more prominent vallenwoods on the slopes of the mountain—a task that, of course, took him several years, especially since, as both poet and engineer, his auguries occasionally misfired. But enough of the trial and error: it is not the dark night of labor that we wish to see in a work of genius, but the flawless and seamless fruit (or stars) of that work.

And so, when the elaborate connection was made—the first helmet safely in the upper branches of a large vallenwood, the second at the ear of our hero in a secluded library alcove (not the one mentioned before), the two connected by a copper wire stretched almost to the point of breaking—young Armavir knelt silently and listened to the world outside.

Where it was raining, the birdsong stilled and the clamor of thunder in the distance growing nearer as Armavir listened to the spatter of rain against the leaves, the gentle rustle of the branches in a rising wind. Lulling sounds, tranquil sounds, and soon the budding engineer, the proto-cellist, the youthful poet slept the sleep of the just and the absent-minded, until louder claps of thunder awakened him, and he found that his head had become lodged rather tightly in the experimental helmet, entangled in copper wire that was itself uncomfortably tight beneath his chin, so that he thought of the ill-fated chickens and shuddered.

It was then that the lightning struck the laboratory of the vallenwood, and our lyrical hero discovered that not only did copper wire conduct heat and sound, but also the considerable energies of lightning itself—energies so violent that he could not remember the seven ensuing years except for fleeting images of sunlight and leaves, the brilliant amber bottoms of three half-filled ale glasses, something about a dwarf and a kender, and when the memory settled, himself seated at the Inn of the Last Home, having aimlessly wandered (as he would say in his immortal but flawed “Song of the Ten Heroes” [18] Printed shamelessly as “Song of the Nine Heroes” in both Chronicles, II, and in Leaves from the Inn of the Last Home . See comments in Section III of this essay.

) “into the heart of the story”

And the rest, my friends, was the story itself. From Solace to Sancrist to Palanthas and further, our hero recording, enshrining the Companions in numbers and song, himself the one who embodied most fully the Gnomish ideal of balance —of balance between action and thought, movement and reflection (in the words of his dear departed sister, “teeter and totter”).

Owing to modesty, of course, many of Armavir’s more heroic exploits never found their way into his poetry; but some—lines and stanzas and staves (sometimes entire passages) in which Armavir appeared as a Companion in his own right—began to find their way out of the story [19] Indeed, the text of Armavir’s poetry was twice the length of the prose account that makes up the greater part of the Chronicles as they currently stand. It was the elves and the humans who saw fit to disregard much of the compelling verse (never, alas, to be printed, for water damage from last month’s flood has destroyed the one remaining copy of the poetry in its original splendor. Here lies one whose name was writ underwater!)

.

For strangely, unaccountably, the Heroes grew distant as the War turned in their favor [20] Oh, they have claimed several reasons for these slights. Claimed that Armavir was overly fond of wine (which is Caramon Majere on his high horse [or on the wagon] I am certain!) and overly fond of young girls, who kept getting younger and younger, larger and larger, as the War continued (this clearly an accusation made by Tanis, who made an incredible fuss over some harmless keyhole observations [see commentary on lines 46-50, “Song of the Ten Heroes,” in Section III of this essay. I wish that only once, someone would ask him who ghosted his “Dear Kitiara” letter, but he’s elf enough—just barely—to get by without questioning] ).

, and even at this late time, though I have sent appropriate letters and pleas to several of the original Companions, I “have yet to hear their answer” (as Armavir concludes in the “Canticle of the Dragon”).

How easily they forget, these Heroes, but in their theft of the poetry to ornament their edited and self-serving story (the water is rising even higher in the chamber: my brother’s old water wings, scarcely damaged by the fall, should hold me up until I have finished writing), in their theft of the poetry they have stolen the clues to their own discovery, their own embarrassment, as a famous fragment shows, as I shall show in other publications—given time, given an audience [21] The Philosophika Gnomikon.

, given a purchase of dry ground in this rapidly drowning tunnel.

As for now, my readers: here is the “Song of the Ten Heroes” with accompanying notes—the first true chronicle of the Dragonlance.

III.

The “Song of The Ten Heroes”

Out of that water a country is rising, impossible

when first imagined in prayer.

For the dedicated reader, I would suggest the following procedure as the most effective way to understand the argument that follows: Go out immediately and buy three more copies of this book. Read the poem from the copy you have at hand, my comments (which follow the poem) from the second copy, and reserve the other two copies on a high shelf in case the waters rise in your living quarters or study, for there are mages aplenty left in Krynn (even if old Sandglass-Eyes has gone Reorx knows where), and the rising tides across the planet may not be the work of the moons. Here then, the poem [22] First appeared as “Song of the Nine Heroes”: Chronicles , II, pp. 5-7.

and commentary:

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.