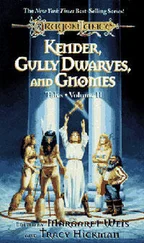

Ник О'Донохью - Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ник О'Донохью - Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1987, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1987

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Nowhere in the pages of Leaves , or in the Chronicles for that matter, is there mention of Armavirumquecanonevermindquiprimusabpedibusfatoprofugit [5] See note above. Henceforth in the text, I refer to our hero as “Armavir.”

, poet and philosopher, an equal and honored Companion in his own right, completely forgotten in favor of a large supporting cast of elves [6] A race of tree surgeons and thieves. True history also has its footnotes.

and gully dwarves [7] A race unworthy of a footnote.

, in favor of the highly overrated Gemstone Man, who is said to have used his highly overrated Gemstone to plug up some metaphysical leak the Companions had imagined because it seemed like good mythology at the time.

But lest we sound nervous or bitter in our attempt to set history right, we shall emphasize the positive—the timeless contribution of Armavir, as we shall call him—the author of most, if not all, of the poetry and songs contained in the Chronicles .

For the elves have assigned this poetry to the pen of one Quivalen Soth [8] Not “Quivalen Sath,” a deceitful (and typically elvish) name change. For evidence see “Song of Huma,” as first printed in Chronicles , I, pp. 442-445.

(for me to imply any relation between this fictitious poet and the infamous Lord Soth might be libelous, so I shall not do so); the kender are as indifferent to who wrote the poetry as they are to anything of honesty and high seriousness; the dwarves as indifferent as they are to anything nonarchitectural or nonmetallic; and the humans seem to be represented on the issue by Caramon Majere (who at last report believed an ode to be a form of salted cracker) and his wife Tika (of whom, alas, I thought better than this betrayal, this insult !). Surely, the poet deserves an account less treacherous, less indifferent, less ignorant. But I grow bitter again, galled by the fading light in my chambers and the endless dripping of the faucets on the south wall, placed there generations ago for Reorx knows what purpose but to gall me with their dripping. I shall fix them this instant; mine is a long and unbearable story, made even less bearable by the perpetual accompaniment of water torture.

As I sit again, I mistrust the passage above, the self-pity that you, my philosophical fellows, may well read into my complaints of neglect, of poor lighting, poor plumbing. I am not a self-pitying gnome, a whiner; my duty is to the name and reputation of Armavir, regardless of my discomfort, of the water knee-deep in these chambers, of the scant light in the chamber from the holes through which, in a far better time than ours, wires and helmets dangled with hope and promise.

His biography and the notes toward an annotated text of his poetry will be my testament, the testament of our people that the tides of history shall not overwhelm us before we recover these songs as our own.

II.

Of Armavir The Poet

A poet is not born but made, as another Gnomish philosopher once said [9] And in saying so, assured another gem that would fall from the mouth of a human!

, and our Armavir was no exception. Born in the midst of the great Gnomish Industrial Revelation (267 A.C.), he was a pampered and protected child who could have expected a Life Quest in keeping with those of his family—a career as an optical illusion inventor or a winch facilitator. Instead, as he said once in a playful moment, he became a topical allusion vendor and a wench facilitator—translated ungraciously by one human [10] Otik Sandahl the Innkeeper. I quote not to give merit to what the innkeeper has said, but to show how petty and unforgiving prejudice can shape history. We historians strive to be generous; after all, I have forgiven Otik’s watering the beer in the Inn of the Last Home.

, who never understood his sensitive and generous poetic soul, as “a gossip and a skirt-chaser.”

As the youngest of three children, Armavir’s life was scarred by early tragedy, his father entangled and dragged to death through a malfunctioning pulley system while facilitating a winch (rumors abounding that he was tied to the fatal rope by a jealous husband), an older brother mistaking the reflection of an onyx ornamental pool for actual water and, clad only in swimsuit and water wings, plunging to his death from atop a fifty-foot stalagmite, an older sister (who, alas, promised in her meager thirteen years to be the genuine beauty of the family) catapulted to her untimely end by an experimental steam-powered seesaw.

Needless to say, it was the lad’s mother (the charming and still active Quacumqueviamvirtutepetivitsuccessumfeminadiranegat [11] See first note Of all the indignities!

) who removed him early from the rough life of mirrors and exploratory physics, leaving him forever with a mistrust of mirages (his poems, as well the reader knows, circle obsessively, skeptically around the image of foxfire) and an even greater mistrust of simple machines.

Isolated by circumstance, by maternal decision, the lad found his chief source of delight in the conversations around him: the retelling of the legends of Krynn we all remember from childhood, those stories beginning with the famous phrase, “The elves tell it otherwise, but this is how it happened”; the recitals of name-histories and genealogies (it is rumored that young Armavir went sleepless for a month to hear three genealogies in their entirety, and that he was “never quite right afterwards” [12] Six weeks sleepless and five genealogies, actually. History foreshortens this achievement because history mistrusts the precocious child.

); but most of all he enjoyed the gossip, of which his mother was chief author, editor, and judge.

Lest this sound like the standard autobiography [13] “The lad found his chief source of delight in the conversations around him”—opening sentence of Bard from Practice: The Autobiography of Quivalin Sath . “The lad found his chief source of delight in the conversations around him”—opening sentence of Rime Amid Reason: The Autobiography of Raggart, Poet of the Ice Barbarians. “The lad found his chief source of delight in the conversations around him”—opening sentence of Song of Solamnia: The Autobiography of Sir Michael Williams, Knight of the Rose . It is ironic how these three minor poets try to conceal their major vanity by writing of themselves in the third person.

, the repetition of the same tired story in which a child falls early in love with the sound and power of words, I shall continue at once with the actual events that sealed Armavir’s poetic calling. For love of language and stories makes for a punster or a tattletale in most children, qualities that do not necessarily blossom into verse unless somehow the child receives enlightenment, direction.

Indeed, Armavir might have lived his life unnoticed in the large and intricate underground kingdom near Mount Nevermind—a minor courtier, a fishwife without fishes—were it not for his brush with death by electrocution, a near—disaster with a happy outcome, for it galvanized his aimless wanderings in legend and gossip into a genuine (if overlooked) poetic gift, and charged him with a restless desire to see the outer world.

It happened as such things often happen—a youthful invention that backfires, but backfires in a most fortunate manner. One does not discard a Life Quest lightly, and Armavir’s quest was what the Guild had pronounced as “Something To Do With Wires”: tensile strength, heat conduction, musical properties—a world of circuit and filament lay before our young hero.

His heart in none of these sciences but the musical, Armavir explored first the variations of sound one could evoke from wires of different thicknesses, tensions, and metals, designing the forerunner of the cello [14] An instrument which would later ennoble his lyrics with music, an instrument later claimed to be of elven make!

. At first the experiments faltered, for Armavir had not chanced upon the idea of making the instrument portable; chambers of the undercity were strung with thin and taut copper wire, hazardous to children, who took it upon themselves to run chickens into those very chambers, thereby decapitating and slicing the creatures in one frolicsome yet practical pursuit [15] See “Gnome Chicken” recipe in Leaves from the Inn of the Last Home , P. 246.

.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.