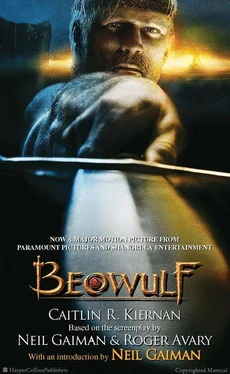

“Yes,” continues Hrothgar. “That’s the spirit we need! You’ll kill my Grendel for me. Let us all drink and make merry celebration for the kill to come! Eh?”

The slave, Cain, helps Unferth to his feet and begins dusting off his clothes. “Get away from me,” Unferth snaps, and pushes the boy roughly aside.

Beowulf smiles a bold, victorious smile, his eyes still on Unferth as he places a hand on old Hrothgar’s frail shoulder.

“Yes, my lord,” says Beowulf. “I will drink and make merry, and then I will show this Grendel of yours how the Geats do battle with our enemies. How we kill. When we’re done here, before the sun rises again, the Danes will no longer have cause to fear the comforts of your hall or any lurking demon come skulking from the moorland mists.”

And now that those assembled in the hall have seen Beowulf’s confidence and heard for themselves his pledge to slay Grendel this very night, their dampened spirits are at last revived. Soon, all Heorot is awash in the joyful, unfettered sounds of celebration and revelry.

“My king,” says Queen Wealthow, as she offers him a large cup of mead, “drink deeply tonight and enjoy the fruits and bounty of your land. And know that you are dear to us.” And when he has finished, she refills the cup, and the Helming maiden moves among the ranks—both Dane and Geat, the members of the royal household and the fighting men—offering it to each in his turn. Only Unferth refuses her hospitality. At the last, she offers the cup to Beowulf, welcoming him and offering thanks to the gods that her wish for deliverance has been granted. He accepts the cup gladly, still enchanted by the beauty of her. When he has finished drinking and the cup is empty, he bows before Hrothgar and his lady.

“When I left my homeland and put to sea with my men, I had but one purpose before me—to come to the aid of your people or die in the attempt. Before you, I vow once more that I shall fulfill that purpose. I will slay Grendel and prove myself, or I will find my undoing here tonight in Heorot.”

Wealthow smiles a grateful smile for him, then leaves the dais and moves again through the crowded mead hall, until she comes to the corner where the musicians have gathered. One of the harpists stands, surrendering his instrument, and she takes his place. Her long, graceful fingers pluck the strings, beginning a ballad that is both lovely and melancholy, a song of elder days, of great deeds and of loss. Her voice rises clearly above the din, and the other musicians accompany her.

Hrothgar sits up straight on his throne and points to his wife. “Is she not a wonder?” he asks Beowulf.

“Oh, she is indeed,” Beowulf replies. “I have never gazed upon anything half so wondrous.” He thinks that perhaps the king is near to tears, the way his old eyes sparkle wetly in the firelight.

Then Beowulf raises his cup to toast Wealthow, who, seeing the gesture, smiles warmly and nods to him from her place at the harp. And it seems to the Geat that there is something much more to her smile than mere gratitude, something not so very far removed from desire and invitation. But if Hrothgar sees it, too, he makes no sign that he has seen it. Instead, he orders Unferth to stand and give up his seat to Beowulf, and Hrothgar pulls the empty chair next to his throne and tells Beowulf to sit. He motions to his herald, Wulfgar, who leaves and soon returns with an elaborately carved and decorated wooden box.

“Beowulf,” says Hrothgar. “Son of Ecgtheow…I want to show you something.” And with that the king opens the wooden box, and the Geat beholds the golden horn inside.

“Here is another of my wonders for you to admire,” the king tells him, and Hrothgar removes the horn from its cradle and carefully hands it to Beowulf.

“It’s beautiful,” Beowulf says, holding the horn up and marveling at its splendor, at its jewels and the bright luster of its gold.

“Isn’t she magnificent? The prize of my treasury. I claimed it long ago, after my battle with old Fafnir, the dragon of the Northern Moors. It nearly cost me my life,” and he leans closer to Beowulf, whispering loudly. “There’s a soft spot just under the neck, you know.” And Hrothgar jabs a finger at his own throat, then points out the large ruby set into the throat of the dragon on the horn. “You go in close with a knife or a dagger…it’s the only way you can kill one of the bastards. I wonder, how many man have died for love of this beauty.”

“Could you blame them?” asks Beowulf, passing the horn back to Hrothgar.

“If you take care of Grendel, she’s yours forever.”

“You do me a great honor,” Beowulf says.

“As well I should. I only wish that I possessed an even greater prize to offer you as reward for such a mighty deed.”

Beowulf turns then from Hrothgar and the splendid golden horn and listens as Queen Wealthow finishes her song. For the first time since his journey began, he feels an unwelcome twinge of doubt—that he might not vanquish this beast Grendel, that he may indeed find his death here in the shadows of Heorot. And watching Wealthow, hearing her, he knows that the dragon’s horn is not the only thing precious to the king that he would have for his own. When she’s finished and has returned the harp to the harpist, he stands and clambers from the dais onto the top of one of the long feasting tables. Wealthow watches, and Beowulf feels her eyes following him. He takes a goblet from one of his thanes and raises it high above his head.

“My lord! My lady! The people of Heorot!” he shouts, commanding the attention of everyone in the hall, and they all stop and look up at him. “Tonight, my men and I, we shall live forever in greatness and courage, or, forgotten and despised, we shall die !”

And a great and deafening cheer rises from his men and from the crowd, and Beowulf looks out across the hall, directly at Queen Wealthow. She smiles again, but this time there is uncertainty and sadness there, and a moment later she turns away.

In his dream, Grendel is sitting outside his cave watching the sunset. It isn’t winter, in his dream, but midsummer, and the air is warm and smells sweet and green. And the sky above him is all ablaze with Sól’s retreat, and to the east the dark shadows of a sky wolf chasing after her. And Grendel is trying to recall the names of the two horses who, each day, draw the chariot of the sun across the heavens, the names his mother taught him long ago. There is a terrible, burning pain inside his head, as though he has died in his sleep and his skull has filled with hungry maggots and gnawing beetles, as though gore crows pick greedily at his eyes and plunge sharp beaks into his ears. But he knows, even through the veil of this dream, that the pain is not the pain of biting worms and stabbing beaks.

No, this pain comes drifting across the land from the open windows and doors of Heorot Hall, fouling the wind and casting even deeper shadows than those that lie between the trees in the old forest. It is the hateful song sung by a cruel woman, a song he knows has been fashioned just so to burrow deep inside his head and hurt him and ruin the simple joy of a beautiful summer’s evening. And Grendel knows, too, that it is not the slavering jaws of the wolf Skoll that the sun flees this day, but rather that song. That song which might yet break the sky apart and rend the stones and boil away the seas.

No greater calamity in all the world than the thoughtless, merry sounds that men and women make, no greater pain to prick at his soul than their joyful music and the fishhook voices of their delight. Grendel does not know why this should be so, only that it is. And he calls out for his mother, who is watching from the entrance of the cave, safe from the fading sunlight.

Читать дальше