Then, with apprehension coiling tightly within him, he released the screen, because there was nothing else he could do.

He cried out. Couldn’t help it.

The immediate pain in his head was brutal: a vise, not knitting needles or a hammer. He’d been right, not that it did him any good now—the screening had been keeping at bay the full impact of where he was.

Eyes tightly closed, gasping for thin, shallow breaths, aware that there were tears on his face, Ned realized he was going to have to phone down after all. He wasn’t even sure he could stay conscious till someone got here to him.

He opened his eyes, forced himself to look up from where he lay. And facing east, he saw the chapel below the summit’s great cross. It wasn’t even far; he’d gotten pretty damned close. They’d have to give him credit for that, wouldn’t they?

There was nobody else up here. No one had heard his cry. Every sane person had passed him already, going down the long slope towards drinks and a shower, sunset and dinner, out of the wind that was blowing here.

Ned felt something else then: a pulse like a probe in his head. He made himself, moving very slowly, sit up. Everything took so much appalling effort, hurt so much. He looked within himself. Cadell’s aura was still there. And the pulse, the signal, was coming from him.

Of course, Ned thought. You’re clueless, Marriner. A loon.

He’d been thinking of Cadell as chasing him, but he’d been screened. The Celt hadn’t been able to see Ned any more than Ned had spotted him down there. Cadell was just powering his way towards the summit, not knowing if Ned was ahead or behind, or anywhere at all.

Now, though, he realized it, and he was making sure Ned knew he was coming.

I should be afraid, Ned thought. He actually felt too weak for fear, as if all he wanted to do, all he could do, was sit here among dust and stones and scrubby little bushes and let the sun go down on these slopes, and on him.

Well, he could make a phone call first. Someone would come. His aunt was in the call-back. His dad was on auto-dial, and so was Greg. Well, not really, in fact. Melanie had done that very funny nine-or ten-digit auto-dial for Greg on Ned’s phone. Then Ned had rigged their phones with ringtones in the middle of the night.

He could almost smile, remembering when he’d called her the next morning at the cathedral. “You will be made to suffer!” Melanie had said, but she’d been laughing.

If they were understanding anything about this properly, she was somehow up above him right now, not that far.

He thought about her laughing that morning, and something in him altered with the memory. Anger, Ned thought, could drive you hard. It could ruin you or make you, like any other really strong feeling, he guessed.

Right now, it pulled him to his feet.

He realized, straightening carefully, that he could handle this pain too. It had been the contrast, the shock of it when the screen went down, that had flattened him. But he was really high now, far above the plain where the battle had been, and he could hold it together for a bit longer. The weakness in his legs was something else, one more thing. Like he really, really needed more. He could almost hear his friend Larry saying that, the guys laughing.

Cadell was coming, and he was aware now that Ned was ahead of him.

With an effort that cost him, Ned shouldered his pack again. Since when were these things so heavy? His legs felt rubbery, the way they could near the end of a cross-country race. But he’d done those races for three years now, he knew this feeling. It was new, and it wasn’t. You could build on what you had experienced, and he’d smashed into walls running before.

That’s what it was all about, the track coach had always told them. You find where your wall is, and you train to push it back, but when you hit it…you go through. If you can do that, you’re a runner. Ned could hear that voice, too, in his mind.

Ned went through. He was almost comically slow. Walking, not running. In places here—he was right below the chapel now—there were loose rocks on the path that could send you tumbling.

He looked back. And this time he saw someone coming, already on the switchback section, steady and strong and fast.

Ned felt like crying, which was really not going to help. He looked ahead. There were two zigzags left, or he could climb. He wasn’t sure he had the strength for that, but he was pretty certain he didn’t have the time not to. He clenched his jaw—an expression one or two people would have recognized—and left the path. He bent to the slanting rock face, using his hands now.

It wasn’t alpine climbing or anything like that. Any normal time, any normal condition, he could have propelled himself up this slope easily. He could have raced guys up here.

Now, two or three times he was sure he was going to fall. His hands were sweaty, and there was sweat in his eyes. He took off the sunglasses, they were sliding down his nose. The light wasn’t as strong now, the sun low, striking the mountain, washing it in late-day colours. He still saw too much red, but not as badly as before, this high up.

Really high, in fact. He pushed himself, feet and hands, digging and pulling, gasping with the effort it cost him. His T-shirt was plastered to his body. His head hurt; it was pulsing. His legs felt as if he were wearing weights. Was this, he thought, what getting old was like? When your body wouldn’t do things you knew it had been able to do? Another essay topic?

Idiot thought. “You’re a loon!” he said aloud, and made himself laugh: the sound sudden and startling in that lonely, windy place. He took strength from it. Anger wasn’t the only thing you could use.

And, falling apart or not, he was up. He pushed with his right foot at a rock. It slipped away, tumbling down the slope, but his hands were on the top now and he scrambled to the last plateau.

He was directly in front of the chapel. He bent over, catching his breath, trying to control his trembling. He was so weak. There was a courtyard, he saw through an arched opening: a well, a low stone wall on the far side overlooking the southern slopes. The sea would be beyond, some distance off, but not all that far.

He glanced back again. Cadell was clearly visible, golden-haired, cutting straight up across all the switchbacks, hand over hand through scrub and bush, disdaining the path. He wouldn’t need paths, Ned thought. He wanted to hate this man—and the other one—and knew he was never going to be able to do that.

He could beat them, though.

It was easier here, on the level ground just below the last steep ridge to the summit and cross. He didn’t have to go up there. If Veracook was right—and it occurred to him that if she wasn’t he had done all this to no purpose at all—he had to head east, not up.

He looked ahead and saw, as she’d said he would, the mountain falling away to the south in a swooping sheet of stone just beyond the cross. The view was spectacular in the light of the westering sun, fast clouds overhead in the wind.

But that wasn’t his route. The garagai was farther along, she’d said. Up one more slope, the one right in front of him, and then down and right along the next rock face.

He looked back one more time. Cadell was moving ridiculously fast. He saw the man lift his head and shout something. He couldn’t hear; the wind was too strong. It could blow you off the mountain, Ned thought, if you were, like, a little kid, or careless.

He dropped his pack against the stone wall of the chapel and pushed himself into a run. A shambling, dragging motion, an embarrassment, a joke, and he couldn’t even keep it going. The slope of this ridge was upwards again, and he was too drained, too spent. The wind from the north, on his left, kept pushing him towards the long slide south. He did slip once, banging his knee. He thought he heard a shout behind him. He didn’t look back.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

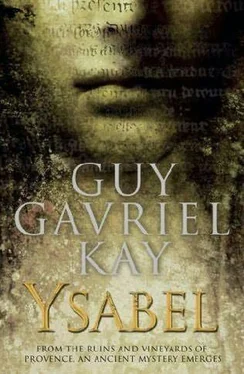

Купить книгу