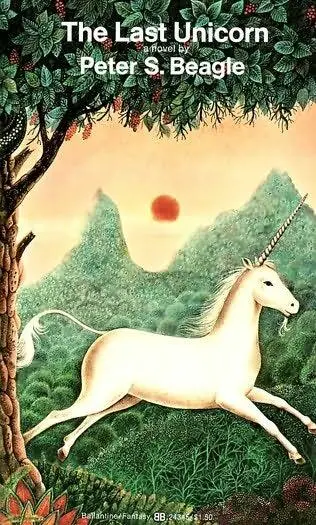

Peter S. Beagle

THE LAST UNICORN

To the memory of Dr. Olfert Dapper, who saw a wild unicorn in the Maine woods in 1673, and for Robert Nathan, who has seen one or two in Los Angeles

The unicorn lived in a lilac wood, and she lived all alone. She was very old, though she did not know it, and she was no longer the careless color of sea foam, but rather the color of snow falling on a moonlit night. But her eyes were still clear and unwearied, and she still moved like a shadow on the sea.

She did not look anything like a horned horse, as unicorns are often pictured, being smaller and cloven-hoofed, and possessing that oldest, wildest grace that horses have never had, that deer have only in a shy, thin imitation and goats in dancing mockery. Her neck was long and slender, making her head seem smaller than it was, and the mane that fell almost to the middle of her back was as soft as dandelion fluff and as fine as cirrus. She had pointed ears and thin legs, with feathers of white hair at the ankles; and the long horn above her eyes shone and shivered with its own seashell light even in the deepest midnight. She had killed dragons with it, and healed a king whose poisoned wound would not close, and knocked down ripe chestnuts for bear cubs.

Unicorns are immortal. It is their nature to live alone in one place: usually a forest where there is a pool clear enough for them to see themselves — for they are a little vain, knowing themselves to be the most beautiful creatures in all the world, and magic besides. They mate very rarely, and no place is more enchanted than one where a unicorn has been born. The last time she had seen another unicorn the young virgins who still came seeking her now and then had called to her in a different tongue; but then, she had no idea of months and years and centuries, or even of seasons. It was always spring in her forest, because she lived there, and she wandered all day among the great beech trees, keeping watch over the animals that lived in the ground and under bushes, in nests and caves, earths and treetops. Generation after generation, wolves and rabbits alike, they hunted and loved and had children and died, and as the unicorn did none of these things, she never grew tired of watching them.

One day it happened that two men with long bows rode through her forest, hunting for deer. The unicorn followed them, moving so warily that not even the horses knew she was near. The sight of men filled her with an old, slow, strange mixture of tenderness and terror. She never let one see her if she could help it, but she liked to watch them ride by and hear them talking.

"I mislike the feel of this forest," the elder of the two hunters grumbled. "Creatures that live in a unicorn's wood learn a little magic of their own in time, mainly concerned with disappearing. We'll find no game here."

"Unicorns are long gone," the second man said. "If, indeed, they ever were. This is a forest like any other."

"Then why do the leaves never fall here, or the snow? I tell you, there is one unicorn left in the world — good luck to the lonely old thing, I say — and as long as it lives in this forest, there won't be a hunter takes so much as a titmouse home at his saddle. Ride on, ride on, you'll see. I know their ways, unicorns."

"From books," answered the other. "Only from books and tales and songs. Not in the reign of three kings has there been even a whisper of a unicorn seen in this country or any other. You know no more about unicorns than I do, for I've read the same books and heard the same stories, and I've never seen one either."

The first hunter was silent for a time, and the second whistled sourly to himself. Then the first said, "My great-grandmother saw a unicorn once. She used to tell me about it when I was little."

"Oh, indeed? And did she capture it with a golden bridle?"

"No. She didn't have one. You don't have to have a golden bridle to catch a unicorn; that part's the fairy tale. You need only to be pure of heart."

"Yes, yes." The younger man chuckled. "Did she ride her unicorn, then? Bareback, under the trees, like a nymph in the early days of the world?"

"My great-grandmother was afraid of large animals," said the first hunter. "She didn't ride it, but she sat very still, and the unicorn put its head in her lap and fell asleep. My great-grandmother never moved till it woke."

"What did it look like? Pliny describes the unicorn as being very ferocious, similar in the rest of its body to a horse, with the head of a deer, the feet of an elephant, the tail of a bear; a deep, bellowing voice, and a single black horn, two cubits in length. And the Chinese —"

"My great-grandmother said only that the unicorn had a good smell. She never could abide the smell of any beast, even a cat or a cow, let alone a wild thing. But she loved the smell of the unicorn. She began to cry once, telling me about it. Of course, she was a very old woman then, and cried at anything that reminded her of her youth."

"Let's turn around and hunt somewhere else," the second hunter said abruptly. The unicorn stepped softly into a thicket as they turned their horses, and took up the trail only when they were well ahead of her once more. The men rode in silence until they were nearing the edge of the forest, when the second hunter asked quietly, "Why did they go away, do you think? If there ever were such things."

"Who knows? Times change. Would you call this age a good one for unicorns?"

"No, but I wonder if any man before us ever thought his time a good time for unicorns. And it seems to me now that I have heard stories — but I was sleepy with wine, or I was thinking of something else. Well, no matter. There's light enough yet to hunt, if we hurry. Come!"

They broke out of the woods, kicked their horses to a gallop, and dashed away. But before they were out of sight, the first hunter looked back over his shoulder and called, just as though he could see the unicorn standing in shadow, "Stay where you are, poor beast. This is no world for you. Stay in your forest, and keep your trees green and your friends long-lived. Pay no mind to young girls, for they never become anything more than silly old women. And good luck to you."

The unicorn stood still at the edge of the forest and said aloud, "I am the only unicorn there is." They were the first words she had spoken, even to herself, in more than a hundred years.

That can't be, she thought. She had never minded being alone, never seeing another unicorn, because she had always known that there were others like her in the world, and a unicorn needs no more than that for company. "But I would know if all the others were gone. I'd be gone too. Nothing can happen to them that does not happen to me."

Her own voice frightened her and made her want to be running. She moved along the dark paths of her forest, swift and shining, passing through sudden clearings unbearably brilliant with grass or soft with shadow, aware of everything around her, from the weeds that brushed her ankles to insect-quick flickers of blue and silver as the wind lifted the leaves. "Oh, I could never leave this, I never could, not if I really were the only unicorn in the world. I know how to live here, I know how everything smells, and tastes, and is. What could I ever search for in the world, except this again?"

But when she stopped running at last and stood still, listening to crows and a quarrel of squirrels over her head, she wondered, But suppose they are riding together, somewhere far away? What if they are hiding and waiting for me?

From that first moment of doubt, there was no peace for her; from the time she first imagined leaving her forest, she could not stand in one place without wanting to be somewhere else. She trotted up and down beside her pool, restless and unhappy. Unicorns are not meant to make choices. She said no, and yes, and no again, day and night, and for the first time she began to feel the minutes crawling over her like worms. "I will not go. Because men have seen no unicorns for a while does not mean they have all vanished. Even if it were true, I would not go. I live here."

Читать дальше