“I will help you if I can,” said a voice; but she was dreaming, and could not be sure if the words were spoken aloud. She looked up from where she sat huddled on the ground; a tall blond man stood near her. He knelt beside her; his eyes were blue, and kind, and anxious. “Aerin-sol,” he said. “Remember me; you have need of me, and I will help you if I can.” A flicker came and went in the blue eyes. “And you shall again aid Damar, for I will tell you how.”

“No,” she said, for she remembered Maur, and knew Maur was real, whether or not she was dreaming now; “no, I cannot. I cannot. Let me stay here,” she begged. “Don’t send me back.”

A line formed between the blue eyes; he reached one hand toward her, but hesitated and did not touch her. “I cannot help it. I can barely keep you here for the space of a dream; you are being pulled back even now.”

It was true. The smell of kenet was in her nostrils again, and the sound of running water in her ears. “But how will I find you?” she asked desperately; and then she was awake. Slowly she opened her eyes; but she lay where she was for a long time.

Eventually she began walking again, leaning heavily on a thick branch she had found and laboriously trimmed to the proper length. She had to walk very slowly, not only for the sake of her ankle, but that her left arm not be shaken too gravely; and she still had trouble breathing. Even when she breathed in tiny shallow gasps it hurt, and when she forgot and sucked in too much air she coughed; and when she coughed, she coughed blood. But her face and arm were healing.

She had also discovered that the hair on the left side of her head was gone, burnt by the same blast of dragonfire that had scarred her cheek. So she took her hunting knife, the same ill-used blade that had been forced to chop her a cane, and sawed off the rest of her hair till none of it was longer than hand’s width. Her neck felt rubbery with the sudden weightlessness, and the wind seemed to whistle in her ears and down her collar more than it used to. She might have wept a little for her hair, but she felt too old and grim and worn.

She avoided wondering what her face looked like under her chopped-off hair. She thought fixedly of other things when she rubbed kenet into her cheek, and when she dressed and rebound her arm. She did not think at all about being willing to face other people again, except to cringe mentally away from the idea. She was not vain as Galanna was vain, but she who had always disliked being noticed was automatically conspicuous as the only pale-skinned redhead in a country of cinnamon-skinned brunettes; she could not bear that her wounds now should make her grotesque as well. It took strength to deal with people, strength to acknowledge herself as first sol, strength to be the public figure she could not help being; and she had no strength to spare. She tried to tell herself that her hurts were honorably won; even that she should be proud of them, that she had successfully done something heroic; but it did no good. Her instinct was to hide.

She had briefly thought with terror that the villagers had sent the messenger to the king that morning so long ago might send another messenger to find out what had become of either sol or dragon; but then she realized that they would do no such thing. If the sol had killed the dragon (unlikely), she would doubtless come and tell them about it. If she didn’t, the dragon could be presumed to have killed her, and they would stay as far away as possible.

At last she grew restless. “Perhaps we should go home,” she said to Talat. She wondered how it had gone with Arlbeth and Tor and the army; it could all be over now, or Damar could be at war, or—almost anything. She didn’t know how long she’d been in the dragon’s valley, and she began to want urgently to know what was happening outside. But she did not yet have the courage to venture out of Maur’s black grave-out where she would have to face people again.

Meanwhile she walked a little farther and a little farther each day: and one day she finally left the steam bank, and hobbled around the high rock that separated the stream from the black valley where Maur lay. As the sound of the stream receded she kept her eyes on her feet; one booted and one wrapped in heavy tattered and grimy rags; and one of them stepping farther than the other. She watched their uneven progress till she passed the rock wall by, and a little gust of burnt-smelling breeze pressed her cheek, and the sound of her footsteps became the slide-crunch, slide-crunch of walking on ash and cinders. She looked up.

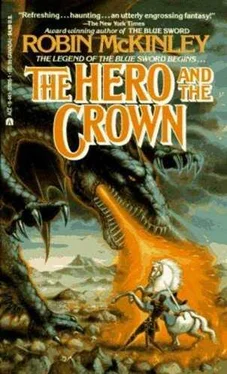

Carrion beasts had not gotten far with the dead dragon. Its eyes were gone, but the heavy hide of the creature was too much for ordinary teeth and claws. Maur looked smaller to her, though; withered and shrunken, the thick skin more crumpled. Slowly she limped nearer, and the small breeze whipped around and stroked her other cheek. There was no smell of rotting flesh in the small valley, although the sun beat down overhead and made her cheek, despite the kenet on it, throb with the heat. The valley reeked, but of smoke and ash; small black flakes still hung in the air, and when the breeze struck her full in the face the cinders caught in her throat and she coughed. She coughed, and bent over her walking stick, and gasped, and coughed again; and then Talat, who had not wanted to follow her into the dragon’s valley but didn’t want to let her out of his sight either, blew down the back of her bare neck and touched his nose to her shoulder. She turned toward him and threw her right arm over his withers and pressed the side of her face into his neck, breathing through the fine hairs of his mane till the coughing eased and she could stand by herself again.

The dragon’s snaky neck lay stretched out along the ground, the long black snout looking like a ridge of black rock. Ash lay more heavily around the dragon than in the rest of the small valley, in spite of the breeze; but around the dragon the breeze lifted a cloud that eddied and lifted and swelled and diminished so that it was hard to tell—as it had been when she and Talat had first ridden to confront the monster—where Maur ended and the earth began. As she watched, another small brisk vagrant breeze swept down the body of the dragon, scouring its length from shoulder hump to the heavy tail; a great black wave of ash reared up in the breeze’s wake and crested, and misted out to drift over the rest of the valley. Aerin hid her face in Talat’s mane again.

When she looked up she stared at Maur, waiting to think something, feel something at the sight of the thing that she had killed, that had so nearly killed her; but her mind was blank, and she had no hatred or bitterness nor any sense of victory left in her heart; it had all been burned away by the pain. Maur was only a great ugly black lump. As she stared, another small breeze kicked up a windspout, a small ashy cyclone, just beyond the end of the dragon’s nose. Something glittered there on the ground. Something red.

She blinked. The wind-spout died away, and the ash fell into new ribs and whorls; but Aerin thought she could still see a small hummock in the ash, a small hummock that dimly gleamed red. She limped toward it, and Talat, his ears half back to show his disapproval, followed.

She stood on one foot and dug with her stick; and she struck the small red thing, which with the impulsion of the blow sprang free of the black cinders, made a small fiery arc through the air, and fell to the earth again, and the ash spun upward in the air draught it made and fell in ripples around it, like a stone thrown into a pond.

Aerin had some trouble kneeling down, but Talat, who had adjusted to his lady’s new slow ways, came and stood beside her and let her clutch her way one-handed down a foreleg. She picked the red thing up; it was hard and glittering and a deep translucent red, like a jewel. “Well,” she whispered. I can’t take the head away as a trophy this time; so I will take this. Whatever it is.”

Читать дальше