Chances were it would still be there in the morning. He could pick it up then, take it out to the sea and wash it clean. Maybe.

‘Oi-oi!’ Berren jumped. He looked around, back up the steps from the doorway. Dim light framed the shape of Club-Headed Jin. ‘Who’s that down there?’

‘Berren,’ said Berren. Jin knew all of Hatchet’s boys. He was easy on them most of the time, as long as they didn’t mess with his women. The older boys often spent their money here, if they had any.

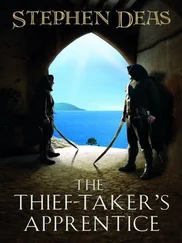

‘Thought you were gone. Heard you’d taken up with a thief-taker. What you doing back here?’

‘I don’t want to be a thief-taker.’ He found he wasn’t nearly as sure of that as he was when he’d left Master Sy. He tried to remind himself of the thief-taker’s temper. Of the flying ink pot that could have taken his head off. Instead he found himself remembering fresh clean water and meals that were simple but at least not stale or mouldy. Remembering walking with Master Sy through the city streets, gawping at everything, pretending to pay attention to what the thief-taker was saying about who lived where and did what and why. Remembering Lilissa.

Jin made a means-nothing-to-me sort of noise. ‘Well you can’t stay here and I doubt Hatchet’s going to take you back. Running away from your master?’ He drew a long breath between his teeth. ‘Boys should know better. Now you’ve run away from two.’

‘I said I didn’t want to be a thief-taker.’ He shouted it up the stairs. ‘Hatchet sold me.’

‘Oi.’ Jin frowned. ‘Keep it down.’

Berren sighed and flopped down on the bottom of the steps. ‘I don’t know where to go.’

‘You’re not staying here.’

‘Where do I go, then?’

‘Home. You stupid?’

‘Up Reeper Hill and through the back of the docks? In the middle of the night?’

Jin thought about this. ‘What’s that smell?’

‘Master Hatchet threw a bucket of pig-swill at me. He missed,’ he added quickly, ‘But it’s all over the alley.’

‘Outside my door?’ Jin made a discontented rumbling noise. ‘We’ll have to have words about that. Who’s going to come in through that stink, eh?’ He blew out a great lungful of air and then shrugged his shoulders. ‘It’s late anyway. Not many fellows about this time of night. I won’t be sheltering one of Master Hatchet’s boys if they’ve crossed him some, but I suppose if you sat down there all through the night and kept very quiet and very still, I might not even notice you were there. Mmmm.’ He shrugged again and then turned and vanished back into his room at the top of the stairs.

‘Thank you, Master Jin.’

‘Quiet and still,’ rumbled a voice.

So he sat on the steps, hugging his knees to his chest to keep warm. At some point he must have nodded off, because when he looked up it was light outside. Not proper daylight, but the grim grey light of dawn. His arms and legs were stiff. The world was quiet. He crept up the steps to look for Master Jin, but the room at the top was empty and he knew better than to go any further; instead he went outside. His shirt was lying in the alley where he’d left it. When he picked it up, the stench almost made him sick. Then he trotted out of the alley and turned right down Loom Street, all the way to the end where it petered out into a shingle beach scattered with ropes and little boats turned upside down, with nets hung up to dry in amongst the broken bones of shattered ships. This was the thin end of the fishing district. South of Wrecking Point and north of The Peak and Deephaven Point was the huge Horseshoe Bay, home of the sea-docks. The waters there were deep and sheltered. North of Wrecking Point, starting here, the waters were shallower and when the winds came in off the sea, they howled straight up the beach and onto the shore. A whole string of small bays and coves were home to the Deephaven fishing fleet; in fact what the city called the fishing district extended for more than twenty miles up the coast and the fishermen who lived in the scattered villages at the far end of that would have been surprised to be told that they lived in Deephaven at all. Deephaven did that. It reached out along its waterways like a greedy prince stretching out to grasp at everything within reach.

Berren felt a pang of anger. Those were Master Sy’s words, from one of the rare times he’d been given a break from beating his head against his letters. They’d walked half a dozen miles together along the bank of the River Arr to see how the city never quite came to an end. Past the river-docks, through Sweetwater and past Sweetwater Bend where rich and poor alike collected drinking water from the river before it flowed beside the city proper. Up into the gentle affluence of the River District, where small markets and expensive riverside inns mixed with open farmland.

He shook himself and picked a path down to the sea. The water was cold this morning, the waves gentle and calm. Most of the fishing boats huddled together on the north side of each cove where they’d have shelter from the weather if they needed it. The southern corners like this became something of a wilderness. Debris washed up from storms past lay scattered about, all the pieces too big or too useless to be carried away. They’d stay until winter, when the beach would be picked clean of its wrecks. Anything that would burn and keep people warm at night.

He wasn’t alone. The fishermen were already up. Old men mostly, down here. The old, the broken. People who eked out a desperate living as best they could. They’d take their little boats and row out into the water and throw out their nets and take what they could from the bay. None of them paid much attention to Berren as they groaned and dragged their boats into the waves. When he’d finished rinsing and wringing out his shirt, Berren stayed and watched them for a while. A breeze was slowly but steadily picking up, the usual wind blowing from the north-west, trying to push the fishermen back onto the shore. They had no choice but to fight it, labouring through the waves, hauling themselves out through the breakers, fighting against the will of the ocean. Berren shuddered. There was always this. Whatever else the city dangled in front of him and then took away, there was always this. He could spend his life breaking his back against the sea just to make sure he didn’t starve.

Of course, if you didn’t come from around here, you wouldn’t know that the leaky boats that these old fishermen used weren’t their own. They paid rent for them, every day, whether they used them or not, to men like Master Hatchet. Most days the rent cost them almost everything they caught.

He shivered again. The wind was chilly and he was already cold. He turned and left the fishermen to their work. He didn’t know where he was going to go, only that it was somewhere else. Anywhere but here.

With nothing better to do, he wandered back up Reeper Hill. Outside the rich houses at the top, a few carriages still stood waiting to take the young princes of the city back home after their all-night orgies. Berren gave them a wide berth. Everyone knew about this part of Reeper Hill. Rich young men only a few years older than him, drunk, bleary-eyed from lack of sleep, intoxicated with the most fashionable drugs from across the sea. Tempting targets, but the mentors and the bodyguards, the snuffers who looked after them, knew all about muggers and pickpockets. Most of the men who stood guard up here were old enough to have fought in the war from before Berren had been born. They were Khrozus’ soldiers, boys from the countryside. They’d eaten rats and dogs and crabs. They’d stripped the beach of seaweed and made it into soup. In the end, they’d eaten each other as they died. They’d seen an emperor’s son crucified alive over the city gates to keep the enemy at bay. And in the end, they’d come through all that and they’d won. A lot of them had stayed.

Читать дальше