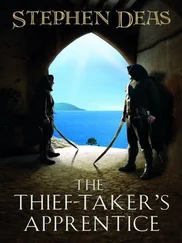

‘Which one is Khrozus?’ he asked. Master Sy actually smiled. It sat awkwardly on his face, as though happiness was something that didn’t come to visit often.

‘Up the top, of course. Right slap in the middle of Four Winds Square, riding his horse. He’s up on Deephaven Square at the top of The Peak too, outside the Overlord’s palace. Khrozus on one side, his son Ashahn on the other. We’ll go to visit them one day, but not today. They don’t let people like us so close to the Overlord’s palace except on festival days.’

A drop of something wet slapped Berren on the nose. He looked up, and heavy drops spattered his face. They’d both been wrong about the rains. As the daily downpour began, he laughed and started to run.

That night Berren went to sleep with a smile on his face. It was a little over a twelvenight since the thief-taker had ripped him away from everything he knew, and for the first time he went to sleep without thinking that tomorrow might be the day he would run away.

It wasn’t. He lasted three more weeks.

Copying the words Master Sy showed him was one thing. Reading them was another; and when it came to taking thoughts in his head and writing them on to paper, he didn’t have the first idea where to start. It took a few days for Berren to realise that he was never, ever going to be able to do what Master Sy wanted him to do, but the thief-taker was relentless. For three weeks, the horror unfolded. Each day, Berren was left in the house to practice his letters while Master Sy went about his business. Each day, he was supposed to copy out a section of some old book with half its pages missing that Master Sy had found. Each day, he was supposed to read back what he’d written. And each day, he couldn’t. Yes, he could copy what was in front of him well enough, possibly even had a knack for it. But when it came to knowing what the words actually meant, he hadn’t the first idea. Couldn’t even begin. Every day the thief-taker came back, tense and frustrated, the afternoon rains dripping from his hat and coat, already anticipating Berren’s failure. He would listen to Berren stumble and make up a few words, and then he’d rage and swear and tear at his hair. Each day got worse and worse.

On the second Mage-Day in the month of Lightning, Berren had a stick in his hand. He was jumping back and forth around the room, lunging and slashing as though it was a sword, shouting curses at imaginary enemies, something he often did to pass the time when he was on his own. Papers lay strewn on the table. The afternoon rains were hammering down outside and the thief-taker never came home until after the rain had stopped.

Berren didn’t even hear the door, only a change in the sound of the rain. When he looked round, Master Sy stood in the doorway. Berren stood frozen, the wooden sword in his outstretched hand, caught in mid-lunge. The thief-taker didn’t even wait for Berren to speak. He took one look at the papers on the table and scattered them across the floor with a sweep of his hand.

‘Boy!’ he roared, lips tight with rage. ‘So this is why you never learn anything! Stupid boy! Do you think this is all for fun?’

Berren skittered around the table, keeping it between them. The look on the thief-taker’s face made him want to run. It was the sort of look that spoke of broken bones and worse. Weeks of frustration welled up inside him. He snatched up the ink pot. ‘It’s not fair!’ he shouted. ‘I can’t do it and I don’t want to do it! None of it makes any sense and I don’t want to learn your stupid letters!’

Master Sy snarled at him, trembling. ‘Boy, sit!’

‘No!’ Berren was holding the ink pot to throw it, but then a mad impulse seized him. Very deliberately he emptied it over the papers littered across the floor. The thief-taker’s eyes bulged. His knuckles clenched white. For a moment he stood rigidly still and then he lunged. Berren dodged him, round the other side of the table. He dropped the ink pot and ran out the door into the rain. ‘I don’t want to learn letters!’ he shouted. ‘Letters are stupid! I want to learn swords and you never show me anything that I want!’

The thief-taker picked up the ink pot and threw it at Berren as hard as he could. It missed his head by inches and smashed on the wall behind him. ‘Get back here, boy!’ He strode to the door. As he did, he picked up a belt. ‘Get back here now!’

Berren backed away, trembling. He’d felt the rush of air past his head when the ink pot had missed. Now the look on the thief-taker’s face was murderous and terrible. Master Sy strode out into the yard and kept on coming, belt in hand. Berren ran. He shot out of the yard, slipping on the wet stone. Through the alley and out into Weaver’s Row, quiet in the afternoon rain. A sharp turn into Button Lane got him into a part of the city he knew well. He glanced over his shoulder. Master Sy wasn’t chasing him. He slowed down to a trot through Craftsmen’s and then zigged and zagged through The Maze, the warren of narrow streets and alleys that separated the Market District from the sea-docks. The rain meant there weren’t many people about. The city was quiet at this time of day. Most folks were in their homes, done with their work for the day, pulling off their boots if they had any and getting ready to take their supper. Then there were the ones who came out after the rains, the ones whose trade were more suited to the evening. They’d be watching the skies, waiting by their doors to rush out as soon as the cloud began to break. As for the ones who came out after dark – well, it wasn’t dark yet.

The Maze slowly merged into the back of the sea-docks. Berren stopped. He stood, bent almost double, hands on his knees to hold the rest of him up, gasping for breath. Once he was quite sure the thief-taker hadn’t followed him, he sat down heavily in a doorway and held his head in his hands.

Master Sy could have killed him with that ink pot. He told himself that again, partly in disbelief, partly to make himself believe. And now he’d run away. Whatever else, that meant he couldn’t go back. Not to someone like that.

So he was never going to see Lilissa again. And he was never going to learn swords after all, or be rich and important and powerful and tell people what to do. It was all a big lie. He bit his lip. Crying never got you anything but jeering and a beating from the older boys, but his eyes burned all the same. Right there and then, he hated the thief-taker more than anyone in the world for showing him so much and then taking it all away again.

The rains slowly relented. The evening sun broke through the cloud and glittered across the bay, already fiery red. It would be dark soon. Reluctantly Berren got up. Wandering the back alleys of the sea-docks at night was no place to be if you were small and on your own, even if you didn’t really have anything worth stealing. There were gangs about who were interested in things other than money. Berren had never run into them, but that was because he was careful. He’d certainly heard the stories. Gangs of men who took boys and dragged them off to sea. Gangs of men who took boys for other reasons. Right now, going out to sea on a ship and never coming back didn’t seem like such a bad thing, but Berren wasn’t sure how you could tell those gangs apart from the other ones.

And anyway, there was always Master Hatchet. It wasn’t as if he didn’t have a place to go. He took a deep breath. Shipwrights was a part of the fishing quarter and the fishing quarter was a huge place, but Loom Street was close enough to the docks. With a bit of luck he could get there before the streets got really dark. He set off again at a run. That was the thing. Never stop anywhere that wasn’t out in the open. Never stop in the shadows. Never stop if someone shouted at you or if a hand grabbed at you. Never stop at all if you could help it. Not here in the back alleys of the sea-docks. He didn’t stop when he reached the harbour and the waterfront either. There was less to fear among the crowds of sailors and the teamsters. Some of them were drunk, but most were still hard at work. The work on the docks never stopped. There were always people there at all hours of the night, hauling bales and crates to and from the boats at the edge of the sea.

Читать дальше