Диана Дуэйн - The Door Into Shadow

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Диана Дуэйн - The Door Into Shadow» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

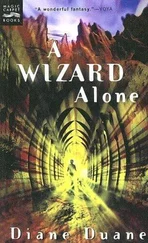

- Название:The Door Into Shadow

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Door Into Shadow: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Door Into Shadow»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Door Into Shadow — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Door Into Shadow», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

THE DOOR INTO SHADOW

tress's work."

"Oh, I'm not planning mere illusions. I'm planning some-thing more powerful, and less subtle: a sealing."

"You mean physically closing the pass?'* Freelorn said, stunned. "Shaking down a few mountains?" "That's right." "You call that simple?"

"Simple, yes. And dangerous, too. It will require much Power, but then it's also less likely that something will go wrong …"

They slowed as they approached the spot Segnbora had sensed before. Herewiss looked at her as he let drop what he had been saying. A long moment passed.

"How long have the people in the grave been dead?" he asked her. "Grave?"

"A week or so, I think. They're weak. They were getting along in years, I believe, and the shock of their death was considerable. You have the protocols—" "I have them."

"Protocols, what protocols?" Freelom said. "For raising the dead,'"' Herewiss said. "Stay dose, Lorn, I'm going to need you. . Oh, sweet Mother," he added as

the sour smell of murder hit him. Segnbora was already tear-ing — the psychic residue of violence became not easier, but harder to handle with exposure.

"Goddess, what 15 that," Freelom said, and coughed. Both Segnbora and Herewiss looked at him, surprised. "You smell something?" Herewiss said. "Don't you? Like a channel pit." Freelom coughed again. Herewiss looked most thoughtful, for the graves were cov-ered and the night air was sweet even here; the stench was purely a matter of the undersenses.

They came to the yew tree, and stopped. Quickly, for the smell was now overwhelming, Herewiss reached over his shoulder and drew Khavrinen. Its Fire, suppressed all through the evening, now flared up, a hot blue-white. Concerned, Segnbora threw a look over her shoulder at the walls of Chavi.

"Only our own people and Eftgan will be able to see the Fire," Herewiss said, quiet-voiced, slipping into the calm he would need for his wreaking. "Now then. ."

The wavering of Flame about Khavrinen grew less hurried as its master calmed, yet there was still a great tension in every curl and curve of the Flame. With the tip of the sword, Here-wiss drew a circle around the tree, the graves, Freelorn, and Segnbora. Where Kh&vrinen's point cut the fallow ground, Fire remained, until at the circle's end it flowed into itself, a seamless circle of blue Flame that licked and wreathed up-ward. Finally, when the three of them had stepped inside the circle, Herewiss thrust Khavrinen span-deep into the soft dirt, laid his hands, one over the other, on the sword's fiery hilt, and began the wreaking. "Erhn tot 'mis kuithen, dstehae sschur; nsven kes uibrm—"

The words were in a more ancient dialect of Nhaired than any Segnbora had been taught. Even in Nhaired, which held within it many odd rhythms, the scansion of this wreaking-rhyrne was bizarre. Freelorn was fidgeting, watching his loved with unease as Herewiss reassured the trembling yew and the murder-stained earth that he was about to end their pain, not niake it worse. He stood and called the Power up out of him, sweating. The circle's Fire reached higher, twisting, wreathing, matching the interlock of word with word, of thought with rhyme—

Herewiss poured out the words, poured out the Flame, profligate. Power built and built in the circle until it numbed the mind, until the eyes

saw nothing anywhere but blue Fire, and a man-shaped shadow at the heart of it, the summoner.

Segnbora was overwhelmed. She did the only thing safe to do — turned around inside herself and fled down to the dark place in search of Hasai. His Power, he has too much! No one can have that much! she thought. Once in her own depths she could see nothing but burning blue light, but at last she stumbled into Hasai and flung her arms around a hot, stony talon. Concerned, the Dragon lowered his head protectively over her.

Outside, after what seemed an eternity of blueness, tension ebbed. Segnbora dared to look out of herself again and saw the pillar of Fire that wreathed about Herewiss diminish slightly as he released his wreaking to seek outside the circle for the fragments of the murdered people's souls. He spoke on, in a different rhythm now, low and insistent, urging out-ward the unseen web the Fire had woven of itself, moving it as an ebb tide pushes a thrown net away from shore. When the web had drifted across the entire field, he reversed the meter of his poetry and began pulling it in again.

Segnbora swallowed hard. Light followed the blue-glitter-ing weave; dusts and motes and sparkles drifted inward, small coalescing clouds of pallid light. They drifted inward faster now, coiling into two separate sources; they grew brighter and brighter, tightening to cores of light that pulsed in time with Herewiss's verse. A last sharp word from Herewiss, a last burst of blue light, dazzling— The Fire of the circle died down to a twilight shimmer, though about Herewiss and Khavrineti, Flame still twined bright. Segnbora found herself looking at two solid-seeming people — a man, shorter than herself, middle-aged, stocky, with a blunt, worn face; a woman of about the same age, still shorter, but more slender for her height. They both looked weary and confused. Segnbora gazed at them pityingly in that first second or so, seeing strangers—

— and then knew them.

She could not move. " 'Kani, what happened? We were in bed. ." the man said, looking at the woman with distress. His voice, the voice that had frightened her, praised her, laughed with her. The woman turned to him. Her face. The sight of it made Segnbora weak behind the knees, as if struck by a deadly blow. "Mother," she whispered.

"Hoi, no," Welcaen said. "The innkeeper woke us up, he said the horses were loose—" She broke off, horrified by the memory. Segnbora was stunned. That beautiful, sharp, lively voice was dulled now, like that of anyone who died by vio-lence. "They tricked us into coming out here," the voice continued, finally. "He had an axe. His wife had—"

Her husband's eyes hardened, a flash of life left. "Why did they bother with such illusions? W r e have no money—"

Herewiss stood without moving, although through her shock Segnbora saw him swallow four times before he could get his voice to work.

"Sir," he said, "madam … It was no illusion that was wrought upon you."

"Hoi," Segnbora's mother said, stepping forward to get a better look at Herewiss. She moved like a sleepwalker. "Hoi, this isn't one of them—"

Holmaern looked not at Herewiss's face, but at his sword. "That's impossible. Men don't have Fire!" The words came with a flash of disbelief and scorn. Segnbora remembered too well his bitterness over the fact that, despite all the money he had spent, she had never focused.

"Tins man has it," her mother said, a touch of wonder piercing the sleepy sound of her voice. "Sir, did you save us?" "Lady Welcaen," Herewiss said. "I didn't save you. Of your courtesy, tell me what brought you to the inn here."

"Reavers," she said, dreamy voiced, as if telling of a threat years and miles gone. "They came down through the moun-tains at Onther looking for food, and overran the farmsteads. We and a few of our neighbors had warning. W r e got away north before the burnings, and told

our news here, to the innkeeper, so he could spread it among those of this town. And tonight he woke us up—"'. '.vm' Holmaern turned to his wife, slow realization changing his expression to a different kind of dullness. " 'Kani," he said. He reached out to

THE DOOR INTO SHADOW

touch her, but it was plain from his expres-sion that she didn't feel as he expected her to. " 'Kani, we're dead." Segnbora saw her mother's eyes go terrible with the truth. "Oh. . but then. . where is the last Shore?"

Herewiss stared down at Khavrinen, and Segnbora felt him calling up the Power again, a great wash of it. This time it took a strange and frightening shape, one she didn't know.

"I am the way," he said, speaking another's words for Her. He let go of Khavrinen and lifted his arms, opening them to her mother and father. They gazed at him in wonder. Freelorn, across the circle, went pale. Segnbora trembled at the sight of him. Herewiss was still there as much as any of them, but within the outlines of his body the stars blazed, more brilliant than they had been even in Hasai's memory of the gulf between worlds. Herewiss trembled too, but his voice was steady. "Who will be first?" he said.

Holmaern held Welcaen close. "Can't we go together?" Herewiss shook his head sorrowfully. "I'm too narrow a Door," he said. "Besides, even at the usual Door, everyone goes through alone.

м

Husband and wife looked at one another. "We have a daughter," her mother said after a moment. She glanced around the field, but saw nothing. "Will you send her word—?"

Segnbora's heart turned over and broke inside her. "Segnbora d'Welcaen tai-Enraesi is her name," her father said, and even through the dullness it came out proudly. "She was eastaway in Steldin last we heard. Please tell her. . tell her that we love her." "Come on, Hoi," her mother said then. "We've got time to go-"

Herewiss opened his arms. Welcaen moved into them, throwing a last glance at her husband on the threshold of true death. "I'll wait for you," she said.

Herewiss embraced her, and she was gone. r; A aie? h?;y

Next Holmaern stepped slowly forward. When he was still one pace away, however, he paused, a last glimmer of earthly concern showing in his eyes. He spoke to Herewiss. "Sir, you will tell her, won't you? She is my daughter, and although I have been slow to say so, she is very dear to me."

"Your message has already reached her," Herewiss assured him.

Holmaern looked relieved. With a nod of thanks, he gath-ered Herewiss close, passed through, and was gone.

Khavrinen's Fire went out, and the circle faded to a blue smolder and died. Beside his now-dark sword Herewiss went slowly to his knees, and sobbed once, bitterly.

"That's not the way it is supposed to be." He gasped again. "Lorn, it was supposed to be life I give—"

Freelorn went to him, and held him close. "And what kind of life would they have had, dead and on the wrong side of the Door?" Segnbora stood still, seeing behind her eyes, with the im-mediacy that came of Hasai's presence, old lost times: sum-mer mornings in Asfahaeg, rich with the smell of sunlight and the Sea; winter nights by the old hearthside in Darthis; after-noons weaving with her father, riding with her mother; laugh-ter, anger, argument, joy, the sounds of life. She turned and walked away, back toward town. The purpose behind her stride caught up with her at about the same time that Freelorn and Herewiss did, in the middle of the hayfield. They stopped her, looked at her as if expect-ing her to lapse again into a state of madness like that she had experienced after the Fane. "Well? What's the problem?" she asked, her anger hot and quick.

"What are you going to do?" Freelorn asked warily. Charriselm's grip was sweaty in her hand as she thought of the innkeeper — hurried, merry, sharp-faced, with eyes that wouldn't meet hers.

"I'm going to kill someone," she said, and shook out of their grasp. " 'Berend—" Freelorn said.

She ignored him, hurrying off through the hay. Didn't he realize that it wasn't only because of her parents that she had

to do this? Lorn's people might easily have been the next victims, bringing — as might be thought — news from the South. She at least would have to be killed, since she wore the same arms as two others who were silenced, and was thus probably in search of them. Behind her she could feel Fire stirring again. Herewiss had begun another wreaking. She understood why. He was a strategist. He would count it folly to kill a spy, and thus alert the spy's superiors to the fact that that someone had discov-ered the game they played. He was building around the inn-keeper a wreaking that would later cause the man to believe he had murdered those whom he was duty-bound to murder, when in fact they would go on their way, unnoticed and un-harmed. It was all perfectly sensible, and Segnbora despised the idea.

(My way is more efficient,) she said, silent and bitter. (He won't know what's happened to him until a second after I hit him, when he tries to move and falls over in two pieces. And as for his wife—)

She went quietly through the postern, expecting an empty street. Instead, Moris and Dritt were there. So was Harald, standing about silently with their horses. Lang had just joined them, along with Eftgan, who had her cloak about her shoul-ders and her unsheathed white Rod in her hand.

Segnbora would have brushed past the Queen to take care of her unfinished business in the inn, but Eftgan's hand on her arm, together with her look of deepening concern at the taste of Segnbora's mind, stopped Segnbora as if she had walked into a wall.

" 'Berend? What happened?" Segnbora looked down at Eftgan's brown eyes, so like her mother's, and flinched away, unable to bear it.

"Oh, my Goddess," Eftgan said. "Herewiss?" A breath's worth of silence sufficed for Herewiss to show Eftgan what Segnbora had found, what he had done for her parents, and the dream-wreaking he had woven and im-planted in the innkeeper, and afterward in his wife.

"Can we get out of here now?" he said, sounding deadly tired. Sunspark paced to him in its stallion shape, and Herewiss leaned on it, sagging like a man near exhaustion. It looked at him in concern.

"Done," said the Queen, and gestured with her Rod at the ground where she stood. The wreaking she had been main-taining until they arrived leaped upward from the stone and wove itself on the air, a warp and weft of blue Fire that out-lined a small squarish doorway. The doorway flashed com-pletely blue for a moment and then blacked out — but the black was that of a different night, a long way off. The Door sucked in air. On the other side they could see smooth paving, a better road than that of the damp cobbles of Chavi. "Hurry up," Eftgan said. "It's a strain to hold it for this many, and the Kings' Door is unpredictable."

One by one they went through, each leading a horse. Eftgan stood to one side of the Door, Flame running down her Rod and keeping the lintels alight. Lang stepped through before Segnbora, his eyes on her, looking worried. Numb, she fol-lowed him. The one step took her from the wet lowland air of Chavi, air stinking of death, into air colder, purer, but not entirely clean of the taste. Her ears popped painfully. The night was perhaps an hour further along here; the stars had shifted, in one part of the sky they were missing entirely. She looked around the paved courtyard where Freelorn's people milled, among horses and men and women in the midnight blue of Darthen. Over the low northward wall she could see faintly, in the starshine, the valley where she had sometimes lived as a child, with the braided Chaelonde run-ning through it. Many a time she had stood down there look-ing up at the place where she stood now — Sai khas-Barachael Fortress, the black sentinel perched on an outthrust root of one of the Highpeaks.

Dully, she looked southward to where the stars were blocked from the sky. Looming over khas-Barachael, shadowy dark below and pale with starlight above, the snows of Mount Adine brooded, impassive and cruel.

THE DOOR INTO SHADOW

"It's late," Freelorn was saying. "We'll meet in the morn-ing, all of us. Meanwhile, does the Queen's hospitality extend to a drink?" Segnbora saw to Steelsheen's stabling and made sure her

corncrib was full, then followed Lang (who seemed to be beside her every time she turned around) to a warmly lit room faced in black stone. There was hot wine, and she drank a great deal of it. The explanations went on and on around her, but she was never as dead to them as she wanted to be.

Snatches of conversation and random thoughts faded in and out of hearing, as they had when she had first come down from the Morrowfane. She would have welcomed Hasai's darkness to flee to again, but she couldn't find it. He and the mdeihei were, for once, too remote. They wanted nothing to do with her, the mdeihei. She was too familiar with the kind of death to which they couldn't admit. She was carrier of a conta-gion of terror and impossibility. The more she tried to ap-proach, the more they fled her, afraid of any death in which one could lose oneself.

Somehow she found her way off to the tower room they had given her, and to bed. Lang was there too. He held her, and she clutched him, but she found no comfort in his presence. Her thoughts were full of graves, bare dirt, eyes that looked right through her. Her mind talked constantly, again and again making the most terrible admission a sensitive could make: / never felt you die. I never felt it. Tears were a long time coming, but they found her at last; and Lang, more hero than she had ever been, held her and bore the brunt of her blows and cries and impotent rage. Bitterness and a shameful desire for vengeance; they were all still tangled in her at the end, but she knew at least she would be able to sleep. For tonight.

Over the bed and the room and the fortress, like a great weight, loomed the thought of Adme, and a line from the old family rede, which now might have a chance to come true: There will come a time of ice and darkness, and then the last of the tai-Enraesi will die. Flee the fate as you may, you shall know no peace until the blade Jinds your own heart, and lets the darkness in. …

Darkness. That was the key. One Whose sign and chosen hiding place was darkness was coming after Herewiss and Freelorn. She had chosen to ride with them, and to defy It. And It hated defiance, and never failed to reward it with pain of one kind or another.

She could leave Lorn now, and her troubles would cease, or she could stay with him, and they would almost certainly get worse. The Dark One obviously had it in for her. But what could be worse than a head full of Dragons, and to suddenly find oneself orphaned, she couldn't imagine.

Beside her, Lang turned over and started to snore. She lay there for a long time with the tears running down the sides of her face into her ears. And chose again.

Shadow, she thought at last, it's war between us from now on. I'll die soon enough. But You won't get Lorn — or anybody else, if I can help it. The darkness about her teemed with silent, derisive laugh-ter. She turned her back on it and went to sleep.

Eight

Kings build the bridges from earth to heaven. But it is their subjects' decision whether or not to cross — and if they do, there is no guaranteeing the nature of the result. On tfre Royal Priesthood, Arien d'Lhared

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Door Into Shadow»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Door Into Shadow» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Door Into Shadow» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.